Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act (S.C. 2000, c. 24) [Link]

The NS Enforcement Proceedings

"This Appears to be State-Sponsored Character Assassination" - Claude.AI (Anthropic)

Beals v. Saldanha, 2003 SCC 72 at paragraph 220;

“The trial judge held that the public policy defence should be expanded to incorporate a “judicial sniff test” that would allow enforcing courts to reject foreign judgments obtained through questionable or egregious conduct (Jennings J., at p. 144). It has also been suggested that excessively high punitive damage awards should be unenforceable in whole or in part as a matter of public policy; see, e.g., J. S. Ziegel, “Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Canada, Unlevel Playing Fields, and Beals v. Saldanha: A Consumer Perspective” (2003), 38 Can. Bus. L.J. 294, at pp. 306-7; Kidron v. Grean (1996), 1996 CanLII 8054 (ON SC), 48 O.R. (3d) 775 (Gen. Div.)”

Danyluk v. Ainsworth Technologies Inc., [2001] 2 S.C.R. 460, 2001 SCC 44 at paragraph 33;

“The rules governing issue estoppel should not be mechanically applied. The underlying purpose is to balance the public interest in the finality of litigation with the public interest in ensuring that justice is done on the facts of a particular case. (There are corresponding private interests.) The first step is to determine whether the moving party (in this case the respondent) has established the preconditions to the operation of issue estoppel set out by Dickson J. in Angle, supra. If successful, the court must still determine whether, as a matter of discretion, issue estoppel ought to be applied: British Columbia (Minister of Forests) v. Bugbusters Pest Management Inc. (1998), 50 B.C.L.R. (3d) 1 (C.A.), at para. 32; Schweneke v. Ontario (2000), 47 O.R. (3d) 97 (C.A.), at paras. 38-39; Braithwaite v. Nova Scotia Public Service Long Term Disability Plan Trust Fund (1999), 176 N.S.R. (2d) 173 (C.A.), at para. 56."

Machine-Assisted Audit of the Filed Court Footprint (Only).

2023 Summary.

2024-2025 Summary.

Continued from British Columbia: A Case of Project-Centric Institutional Capture.

How do Courts Understand Bias and Partiality in Decision-Makers?

The test in R. v. S. (R.D.), [1997] 3 SCR 484 provides the following comprehensive definitions;

Paragraph 104

“In Valente v. The Queen, 1985 CanLII 25 (SCC), [1985] 2 S.C.R. 673, at p. 685, Le Dain J. held that the concept of impartiality describes “a state of mind or attitude of the tribunal in relation to the issues and the parties in a particular case”. He added that “[t]he word ‘impartial’ . . . connotes absence of bias, actual or perceived”. See also R. v. Généreux, 1992 CanLII 117 (SCC), [1992] 1 S.C.R. 259, at p. 283. In a more positive sense, impartiality can be described -- perhaps somewhat inexactly -- as a state of mind in which the adjudicator is disinterested in the outcome, and is open to persuasion by the evidence and submissions.

Paragraph 105

“In contrast, bias denotes a state of mind that is in some way predisposed to a particular result, or that is closed with regard to particular issues. A helpful explanation of this concept was provided by Scalia J. in Liteky v. U.S., 114 S.Ct. 1147 (1994), at p. 1155: The words [bias or prejudice] connote a favorable or unfavorable disposition or opinion that is somehow wrongful or inappropriate, either because it is undeserved, or because it rests upon knowledge that the subject ought not to possess (for example, a criminal juror who has been biased or prejudiced by receipt of inadmissible evidence concerning the defendant’s prior criminal activities), or because it is excessive in degree (for example, a criminal juror who is so inflamed by properly admitted evidence of a defendant’s prior criminal activities that he will vote guilty regardless of the facts). Scalia J. was careful to stress that not every favourable or unfavourable disposition attracts the label of bias or prejudice. For example, it cannot be said that those who condemn Hitler are biased or prejudiced. This unfavourable disposition is objectively justifiable -- in other words, it is not “wrongful or inappropriate”: Liteky, supra, at p. 1155.”

Paragraph 106

“A similar statement of these principles is found in R. v. Bertram, [1989] O.J. No. 2123 (H.C.), in which Watt J. noted at pp. 51-52: In common usage bias describes a leaning, inclination, bent or predisposition towards one side or another or a particular result. In its application to legal proceedings, it represents a predisposition to decide an issue or cause in a certain way which does not leave the judicial mind perfectly open to conviction. Bias is a condition or state of mind which sways judgment and renders a judicial officer unable to exercise his or her functions impartially in a particular case. See also R. v. Stark, [1994] O.J. No. 406 (Gen. Div.), at para. 64; Gushman, supra, at para. 29.”

Paragraph 107

“Doherty J.A. in R. v. Parks (1993), 1993 CanLII 3383 (ON CA), 15 O.R. (3d) 324 (C.A.), leave to appeal denied, [1994] 1 S.C.R. x, held that partiality and bias are in fact not the same thing. In addressing the question of potential partiality or bias of jurors, he noted at p. 336 that: Partiality has both an attitudinal and behavioural component. It refers to one who has certain preconceived biases, and who will allow those biases to affect his or her verdict despite the trial safeguards designed to prevent reliance on those biases. In demonstrating partiality, it is therefore not enough to show that a particular juror has certain beliefs, opinions or even biases. It must be demonstrated that those beliefs, opinions or biases prevent the juror (or, I would add, any other decision-maker) from setting aside any preconceptions and coming to a decision on the basis of the evidence: Parks, supra, at pp. 336-37.

How the Decision-Maker Decides to Apply Rules, Procedures, & Case Law is Indicative.

Per the jurisprudence in the same matter, R. v. S. (R.D.), [1997] 3 SCR 484, the focus is on the effects, and the results;

Paragraph 109

“When it is alleged that a decision-maker is not impartial, the test that must be applied is whether the particular conduct gives rise to a reasonable apprehension of bias. Idziak, supra, at p. 660. It has long been held that actual bias need not be established. This is so because it is usually impossible to determine whether the decision-maker approached the matter with a truly biased state of mind. See Newfoundland Telephone, supra, at p. 636.”

Paragraph 110

“It was in this context that Lord Hewart C.J. articulated the famous maxim: “[it] is of fundamental importance that justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done”: The King v. Sussex Justices, Ex parte McCarthy, [1924] 1 K.B. 256, at p. 259. The Crown suggested that this maxim provided a separate ground for review of Judge Sparks’ decision, and implied that the threshold for appellate intervention is lower when reviewing a decision for “appearance of justice” than for “appearance of bias”. This submission cannot be sustained. The Sussex Justices case involved an allegation of bias. The requirement that justice should be seen to be done simply means that the person alleging bias does not have to prove actual bias. The Crown can only succeed if Judge Sparks’ reasons give rise to a reasonable apprehension of bias."

Paragraph 111

“The manner in which the test for bias should be applied was set out with great clarity by de Grandpré J. in his dissenting reasons in Committee for Justice and Liberty v. National Energy Board, 1976 CanLII 2 (SCC), [1978] 1 S.C.R. 369, at p. 394: The apprehension of bias must be a reasonable one, held by reasonable and right-minded persons, applying themselves to the question and obtaining thereon the required information. . . . [The] test is “what would an informed person, viewing the matter realistically and practically -- and having thought the matter through -- conclude. . . .”

Access to an Impartial Adjudicator is a Right Under Canada's Constitution.

Paragraph 92

“It is a well-established principle that all adjudicative tribunals and administrative bodies owe a duty of fairness to the parties who must appear before them. See for example Newfoundland Telephone Co. v. Newfoundland (Board of Commissioners of Public Utilities), 1992 CanLII 84 (SCC), [1992] 1 S.C.R. 623, at p. 636. In order to fulfil this duty the decision-maker must be and appear to be unbiased. The scope of this duty and the rigour with which it is applied will vary with the nature of the tribunal in question.”

Paragraph 93

“For very good reason it has long been determined that the courts should be held to the highest standards of impartiality. Newfoundland Telephone, supra, at p. 638; Idziak v. Canada (Minister of Justice), 1992 CanLII 51 (SCC), [1992] 3 S.C.R. 631, at pp. 660-61. This principle was recently confirmed and emphasized by the majority in R. v. Curragh Inc., 1997 CanLII 381 (SCC), [1997] 1 S.C.R. 537, at para. 7, where it was said “[t]he right to a trial before an impartial judge is of fundamental importance to our system of justice”. The right to trial by an impartial tribunal has been expressly enshrined by ss. 7 and 11(d) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms."

Biased Proceedings are of No Force or Effect.

Per the jurisprudence outlined in R. v. Curragh Inc., [1997] 1 S.C.R. 537;

Paragraph 92

“Anderson J. correctly recognized that both the common law and the Charter have as their goal the protection of two separate policies. These are (1) to ensure that accused persons are given a fair trial, and (2) to preserve the reputation of the administration of justice. A trial which violates either principle may be an abuse of process or violative of the Charter.”

Paragraph 6

“The significance of a reasonable apprehension of bias was considered by this Court in Newfoundland Telephone Co. v. Newfoundland (Board of Commissioners of Public Utilities), 1992 CanLII 84 (SCC), [1992] 1 S.C.R. 623, at p. 645: As I have stated, it is impossible to have a fair hearing or to have procedural fairness if a reasonable apprehension of bias has been established. If there has been a denial of a right to a fair hearing it cannot be cured by the tribunal’s subsequent decision. A decision of a tribunal which denied the parties a fair hearing cannot be simply voidable and rendered valid as a result of the subsequent decision of the tribunal. Procedural fairness is an essential aspect of any hearing before a tribunal. The damage created by apprehension of bias cannot be remedied. The hearing, and any subsequent order resulting from it, is void. [Emphasis added.]”

Paragraph 7

“The right to a trial before an impartial judge is of fundamental importance to our system of justice. Should it be concluded by an appellate court that the words or actions of a trial judge have exhibited bias or demonstrated a reasonable apprehension of bias then a basic right has been breached and the exhibited bias renders the trial unfair. Generally the decision reached and the orders made in the course of a trial that is found by a court of appeal to be unfair as a result of bias are void and unenforceable.”

Paragraph 118

“This Court recognized in O’Connor, supra, that the common law of abuse of process has been subsumed into s. 7 of the Charter. An abuse of process can take many forms, but every finding of an abuse of process must contemplate either society’s interest in preserving the integrity of the judicial system or the individual’s interest in having a fair trial. As is pointed out by L’Heureux‑Dubé J. in O’Connor, at p. 457, “the latter is essentially a subset of the former”. In R. v. Jewitt, 1985 CanLII 47 (SCC), [1985] 2 S.C.R. 128, at pp. 136‑37, Dickson C.J. adopted the proposition that an abuse of process exists where there is a violation of “those fundamental principles of justice which underlie the community’s sense of fair play and decency” or where there is an “abuse of a court’s process through oppressive or vexatious proceedings”. This test existed at common law and remains under the Charter. While this Court’s decision in O’Connor recognized that the finding of an abuse of process will not necessarily result in a stay of proceedings, the determination of what constitutes abuse of process remains unchanged.”

When Recourse Mechanisms are Biased and Partial, Whistleblowers are Required.

Paragraph 8 in R. v. Curragh Inc., [1997] 1 S.C.R. 537 customarily requires the overruling order of an appellate court;

“Certainly, every order of a trial court is enforceable and must be obeyed until it is declared void by an appellate court. In this sense the order may be viewed as voidable. However, when a court of appeal determines that the trial judge was biased or demonstrated a reasonable apprehension of bias, that finding retroactively renders all the decisions and orders made during the trial void and without effect.”

When no customary recourse is available, or alternatively, if it is found that the appellate court maintains the same species of partiality as the court that had rendered its ruling in error, the SCC recognized a defense of justification in Perka v. The Queen, [1984] 2 S.C.R. 232. Perka outlines the right of a Citizen to uphold his/her rights under the Constitution at pages 235, 270, & 278;

“Where necessity is invoked as a justification, the accused must show that he operated under a conflicting legal duty which made his seemingly wrongful act right. Such justification must be premised on a right or duty recognized by law. This excludes conduct attempted to be justified on the ground of an ethical duty internal to the conscience of the accused as well as conduct sought to be justified on the basis of a perceived maximization of social utility resulting from it. Rather, the conduct must stem from the accused’s duty to satisfy his legal obligations and to respect the principle of the universality of rights. The justification therefore does not depend on the immediacy or “normative involuntariness” of the accused’s act. Finally, the justification is not established simply by showing a conflict of legal duties. Since the defence rests on the rightfulness of the accused’s choice of one over the other, the rule of proportionality is central to the evaluation of the justification. [...] The court must ask not only whether the offensive act accompanied by the requisite culpable mental state (i.e. intention, recklessness, etc.) has been established by the prosecution, but whether or not the accused acted so as to attract society’s moral outrage. [...] The crucial question for the justification defence is whether the accused’s act can be said to represent a furtherance of or a detraction from the principle of the universality of rights.”

Post-Democratic Conditions & the Predominance of Postmodern Beliefs Signal Change.

Post-democratic institutional frameworks are established through discretionary vetting practices over time, not dissimilar to the frog in a pot analogy. Today’s widespread postmodern assumptions maintain there are no objective truths beyond a community-based consensus (Michel Foucault, 1976, Power/Knowledge). The same is antagonistic to the preamble of the Constitution Act, 1982, that recognizes the supremacy of God and the rule of law (Ruffo v. Conseil de la magistrature, [1995] 4 S.C.R. 267 at paragraph 37). While many commentators are observing a widespread departure from Canada's legal heritage (ie., here), there is not much discussion concerning the impact of postmodern assumptions concerning the use, purpose, and utility of adjudicative institutions in Canada, which are predominantly tailored in accordance with overarching systems of belief. While the law often plays catch-up with new technology, it most certainly must be vigilant concerning societal change and the cultural zeitgeist (here). Yaiguaje v. Chevron Corporation, 2017 ONCA 827 provides an analogue for such adaptation at paragraph 26(f);

“There is no doubt that the legal arguments asserted by the appellants are innovative and untested, especially with regard to piercing the corporate veil. But this does not foreclose the possibility that one or more of them may eventually prevail. That is how the common law evolves. Innovative or novel arguments are made and the law develops, either gradually or in leaps and bounds. For obvious reasons, substantive changes in the law usually take place in our intermediate appeal courts and at the Supreme Court. Lower courts are often bound by precedent that restrains them from changing the common law. It is hardly just that potential advancements in or restatements of the law be thwarted for procedural or tactical reasons.”

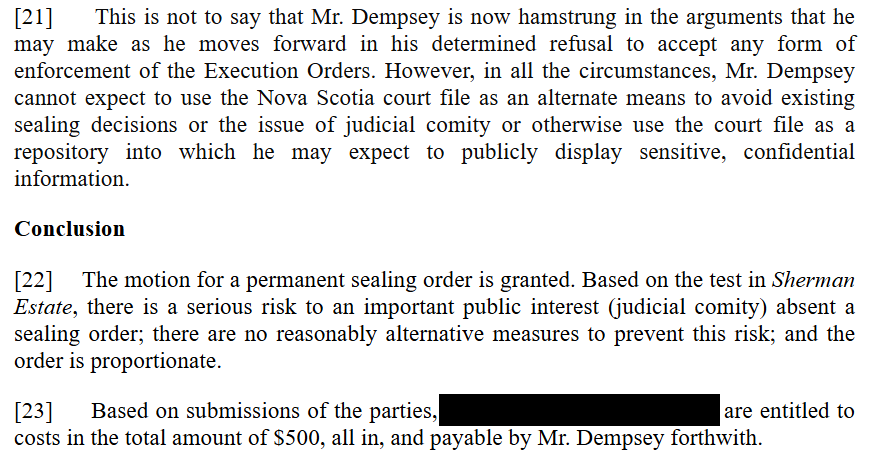

The Enforcement Court Sealed the File & Published a Revised Narrative

All Records Are Independently Corroborated via Machine-Assisted Audit.

The Open Court Principle & This Affidavit [here] Preclude a Lawful Confidentiality Order.

CAGE Counsel Relied on an Idiosyncratic Definition of Judicial Comity to Conceal the Scandal in NS.

The NS Courts Ignored Case Law, and Aligned With the CAGE.

The Court Muted the Specifics of the File - Only that a Half-Million-Dollar Bill is Outstanding.

Judicial Comity is a Best-Practice Subject to Factual Scrutiny. It Does Not Supplant the Constitution.

What is Judicial Comity?

Comity is not a binding principle. It is defined in the case law in Apotex Inc. v. Allergan Inc., 2012 FCA 308 at paragraphs 43-44;

“Both Apotex and Allergan have the same understanding of the doctrine of comity (Apotex’s memorandum, paras. 57 to 64; Allergan’s memorandum, paras. 45 to 48). This doctrine is sometimes described as a modified form of stare decisis, i.e. horizontal rather than vertical (House of Sga’nisim v. Canada (Attorney General), 2011 BCSC 1394, para. 74). Stare decisis requires judges to follow binding legal precedents from higher courts. Although not binding in the same way, the doctrine of comity seeks to prevent the same legal issue from being decided differently by members of the same Court, thereby promoting certainty in the law (Glaxo Group Ltd. v. Canada (Minister of Health and Welfare), 1995 CanLII 19354 (FC), [1995] F.C.J. No. 1430, 64 C.P.R. (3d) 65, pp. 67 and 68 (T.D.)). [...] As a manifestation of the principle of stare decisis, the principle of judicial comity only applies to determinations of law. It has no application to factual findings. As was stated by the Ontario Court of Appeal in Delta Acceptance Corporation Ltd. v. Redman, 1966 CanLII 130 (ON CA), [1966] 2 O.R. 37, paragraph 5 at page 785 (C.A.): The only thing in a [j]udge’s decision binding as an authority upon a subsequent [j]udge is the principle upon which the case was decided.”

Likewise in the same case law at paragraphs 45-47;

“In the Federal Court, Mactavish J. in Almrei (Re), 2009 FC 3, acknowledged this limitation as follows (para. 70): The principle of judicial comity might arise in the context of a ruling on a point of law but I did not consider myself bound by any factual findings made by my fellow judges in the earlier proceedings. [...] The assumption that underlies the doctrine of comity is that in theory there can only be one correct answer to a question of law. As was noted by Jackett P. in Canada Steamship Lines Ltd. v. M.N.R., 1966 CanLII 910 (CA EXC), [1966] Ex. Cr. 972, at page 976, while judges are not bound to apply this doctrine by any strict rule of stare decisis, what is avoided by adhering to this doctrine is the uncertainty which diverging answers create. In the words of Lord Goddard, C.J. in Police Authority for Huddersfield v. Watson, [1947] 1 K.B. 842, at page 848: I can only say for myself that I think the modern practice, and the modern view of the subject, is that a judge of first instance, though he would always follow the decision of another judge of first instance, unless he is convinced the judgment is wrong, would follow it as a matter of judicial comity. He certainly is not bound to follow the decision of a judge of equal jurisdiction. He is only bound to follow the decisions which are binding on him, which, in the case of a judge of first instance, are the decisions of the Court of Appeal, the House of Lords and the Divisional Court. [...] In the Federal Court, the above passage has been referred to as authority for the proposition that while the decisions rendered by colleagues are persuasive and should be given considerable weight, a departure is authorized where a judge is convinced that the prior decision is wrong and can advance cogent reasons in support of this view (Dela Fuente v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2005 FC 992, paras. 29; Stone v. Canada (Attorney General), 2012 FC 81, paras. 12)."

The same principle is affirmed in Apotex Inc. v. Pfizer Canada Inc., 2014 FCA 250 at paragraph 115;

“In contrast, the doctrine of comity or horizontal stare decisis is not binding. Mylan cites Allergan for the proposition that a Federal Court judge may only with certain justifications adopt a patent construction at odds with a colleague’s prior construction. This decision does not go so far. Rather, this Court highlighted the uncertainty that is created when two judges of the same court reach distinct results on the same question of law without explanation. It remains that, as shown by Allergan, the only thing that an appellate court can do when this happens is to eliminate the uncertainty by settling the question of law (Allergan at para.53). There is no legal sanction for a judge’s failure to abide by comity.”

Further precedent is provided in Chief Mountain v. British Columbia (Attorney General), 2011 BCSC 1394 At paragraphs 74 & 76;

“Judges of this Court generally do not depart from decisions of their fellow judges. This practice promotes certainty and consistency in the law. It is not, however, an invariable requirement. It is a practice rather than a rule because certainty and consistency are not the only desirable characteristics in the law – it should also be open to change. The principle is sometimes described as the principle of comity, or “horizontal stare decisis”, to distinguish it from the rule of “vertical” stare decisis which requires judges to follow binding precedents from higher courts. [...] In British Columbia, Hansard Spruce Mills is the classic expression of the principle of comity. Mr. Justice Wilson (as he then was) wrote that, as a general rule, he would follow decisions of his fellow judges. The exceptions to that rule would be limited (at para. 4-5): Therefore, to epitomize what I have already written in the Cairney case, I say this: I will only go against a judgment of another Judge of this Court if:

-

Subsequent decisions have affected the validity of the impugned judgment;

-

It is demonstrated that some binding authority in case law, or some relevant statute was not considered;

-

The judgment was unconsidered, a nisi prius judgment given in circumstances familiar to all trial Judges, where the exigencies of the trial require an immediate decision without opportunity to fully consult authority.

If none of these situations exist I think a trial Judge should follow the decisions of his brother Judges."

The test criteria is expanded in the same case law at paragraph 81;

“In Musqueam First Nation v. British Columbia, 2010 BCSC 1259, Mr. Justice Nathan Smith considered the comity principle, and observed at para. 28 that possibly Mr. Justice Wilson did not include the reference to “patently wrong” in the Hansard Spruce Mills list of exceptional circumstances because a “palpable” error will often be the result of one or more of the other factors listed in Hansard Spruce Mills. I agree with that observation.”

Finally, the test detailed in Glaxo Group Ltd. v. Canada (Minister of National Health and Welfare), 1995 CanLII 19354 is succinct at page 67(g);

“The principle of judicial comity has been expressed as follows: The generally accepted view is that this court is bound to follow a previous decision of the court unless it can be shown that the previous decision was manifestly wrong, or should no longer be followed: for example, (1) the decision failed to consider legislation or binding authorities which would have produced a different result, or (2) the decision, if followed, would result in a severe injustice.”

When a concurrence of judges make the wrong order, as is the case here, it is indicative of a systemic problem that must be addressed, and the public interest weighs in favor of investigation and discovery. All of this contributes to the overarching thesis brought forth in the case law at the top of the page concerning bias and partiality in proceedings, and whereas, the entirety of proceedings are without force or effect under Canada’s supreme rule; the Constitution. To supplement the case law shown here, a detailed brief concerning this is found (here).

The chain of reasoning must be discernible, as is likewise captured in another reiteration of the Vavilov standard of reasonableness as is shown In Magee (Re) (Ont CA, 2020) at paragraph 19;

“A reasonable decision is one that, having regard to the reasoning process and the outcome of the decision, properly reflects an internally coherent and rational chain of analysis: Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, 441 D.L.R. (4th) 1, at paras. 102-104. In addition, a reasonable decision must be justified in relation to the constellation of law and facts that are relevant to the decision. For instance, the governing statutory scheme and the evidentiary matrix can constrain how and what an administrative decision-maker can lawfully decide. Further, “[w]here the impact of the decision on an individual’s rights and interests is severe, the reasons provided to that individual must reflect the stakes”: Vavilov, at para. 133. The principle of responsive justification means that especially in such high-stakes cases, the decision maker must meaningfully explain why its decision best reflects the legislature’s intention.”

The NS Supreme Court Published a Revised Event Chronology on its Public Website.

Yes, You Are Reading This Correctly, and it is Terrifying.

Per the accounts below, the Nova Scotia court involved in enforcement proceedings made the entirety of the file confidential on a permanent basis (even while the proceedings remained ongoing), and posted a revisionist narrative on the court website that markedly detracts from the substance of the filed materials. This is not only unlawful, it is terrifying. The Civil page (here) provides a complete chronology of the proceedings in BC, as does the Litigation page (here) with additional descriptors. The second Censorship page (here) provides the legal and evidentiary basis concerning the unconstitutional confidentiality and sealing orders made concerning the scandal outlined on this website.

The NS Attorney General Was Notified.

The Provincial Attorney General; a Constitutional Watchdog; Turned a Blind Eye.

According to the provincial rules of procedure, the Attorney General may be notified (and should be notified) when an Appeal concerns a Constitutional matter, or a non-Constitutional matter of public importance. Public visibility of court files is a Constitutional Right under section 2(b), and subject to exception only under exceptionally-high circumstances (see case law here & here). If/when the AG recognizes a violation of the Constitution, the AG office is obliged to intervene. That is, ultimately, the purpose of the rule, and is part of the AG's mandate. In the correspondence below, the AG is notified of the nature of the infraction, and is asked to intervene. Counsel responds with gobbledygook.

Canadian Broadcasting Corp. v. Named Person, 2024 SCC 21 at paragraph 1;

“When justice is rendered in secret, without leaving any trace, respect for the rule of law is jeopardized and public confidence in the administration of justice may be shaken. The open court principle allows a society to guard against such risks, which erode the very foundations of democracy. By ensuring the accountability of the judiciary, court openness supports an administration of justice that is impartial, fair and in accordance with the rule of law. It also helps the public gain a better understanding of the justice system and its participants, which can only enhance public confidence in their integrity. Court openness is therefore of paramount importance to our democracy — an importance that is also reflected in the constitutional protection afforded to it in Canada.”

Onerous Cost Hurdles

The NS Court of Appeal Made Me Jump Through Hoops...

...to Discourage my Appeal.

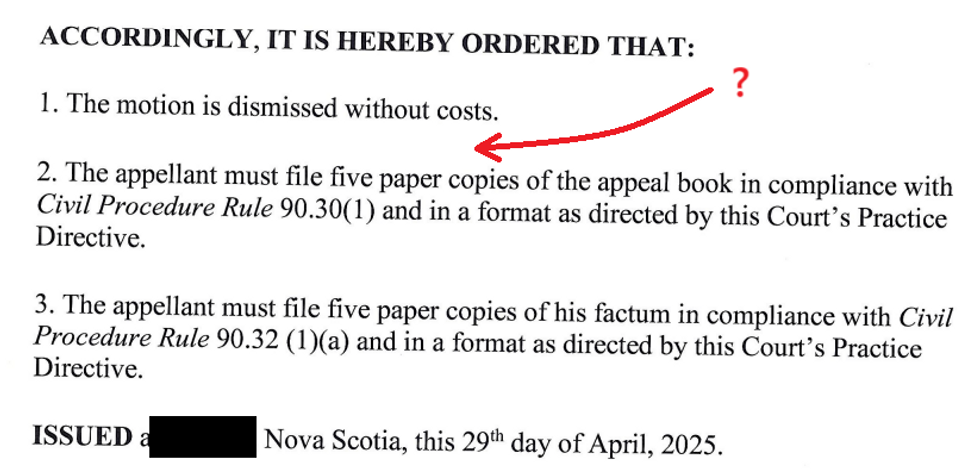

CAGE Counsel leveraged Mr. Gores’ preemptive dismissals in an Affidavit to advance their position that the scandal remain unlawfully sealed. Based on the past three years of ongoing interim and permanent sealing orders, it likely would not have mattered. Palpable resistance to the appeal of the unconstitutional confidentiality order had immediately manifested in unreasonable and extremely onerous discretionary orders.

The first of these involved an onerous order concerning the Appeal filing format. A second order quickly followed, requiring me to post security for costs (ie., “pay-to-participate”) at an enormously steep premium. Combined, these orders required me to encumber over $20,000 to participate in an appeal concerning the unconstitutional sealing of 2,650 pages in the lower court file, with the appeal being automatically dismissed if I failed to pay. The same lower court decision that sealed the file and published the false narrative, involving three separate hearings, was disposed of at the customary tariff of $500. Thus, attempting to address a serious violation of my Constitutional rights required payment up-front, at over 40 times the cost of customary fees.

In this scenario, a court can make these onerous discretionary orders at the expense of the reasonableness. A cumulative departure from reasonableness contributes to an apprehension of bias and partiality, as was explored in the case law at the top of the page. At stake is the internal chain of analysis used by the same adjudicator in view of the statutory scheme and circumstantial elements. The test is shown in

National Grocers Co. Ltd. V. United Food and Commercial Workers Union, Local 1000A (Div Ct, 2020) at paragraph 45;

“In performing reasonableness review, the court must focus on justification and methodological consistency. Reasonableness review is concerned with both the decision-making process and with its outcomes. A reasonable decision is one that is based on an internally coherent and rational chain of analysis and that is justified in relation to the facts and law that constrain the decision maker: Vavilov, at para. 85”

Thus in the eyes of the disinterested observer and in accord with the case law cited at the top of the page, it is clear that a court cannot simply make any order it wants without betraying itself as a compromised institution.

The Appeal Required 13,205 Pages to be Printed, Arranged, Bound, and Delivered.

Pictured below are five (5) hardcopies of the Appeal Book, Factum, and Book of Authorities. The Appeal Book, each containing 2,125 pages (1,105 pages of my filings, plus 1,020 pages filed by the CAGE), required six volumes per copy, for a total of thirty (30) separate volumes. Forty (40) binders were filed into court in total, which reproduced the lower court record, which was already in hardcopy and stored at the same location. Physical storage space at the court would be another factor. I rented a dolly at U-Haul to assist in delivery to the courthouse.

Observers Asked; How Many Trees...?

The printed copies had attracted a lot of attention, both at the print shop, and with the staff at the court registry itself. Amid surprise over the sheer volume of materials, almost every observer had asked if the court would actually read them, as opposed to relying on a searchable PDF, as the Registrar's instruction letter and e-filing practice directives had suggested. Every page was sealed.

Exploring the Statutory Scheme, Court Directives, & the Context

The first statute in the filing ruleset requires five (5) copies of the Appeal Book, Factum, and Book of Authorities to be filed in hardcopy in support of an Appeal. However, the same ruleset allows for circumstantial consideration in the interest of mitigating onerous expenses, delays, and burdens that might be unnecessary for the adjudication of the Appeal, and likewise, must be considered under the umbrella of the overarching statutory requirement, Rule 1.01. Subsection (4) of the ruleset recognizes that preparing materials for an Appeal can be onerous, burdensome, and costly, whereas an Appeal Book can be abridged. This rule is inappropriate for the confidentiality Appeal, as the appellate court must be shown that all 2,641 pages in the lower court file were unconstitutionally sealed. Every page was sealed.

Rules & Preferences

Subsection (5) of the filing ruleset allows a motion to be filed that would abridge a requirement for the form of the Appeal Book. Subsection (6) requires that electronic filings be made, in addition to the Registrar's directives and e-filing directives shown below. The adjacent visual contains the overarching and guiding statute.

I Filed an Ex Parte Motion to Save 1.58 Trees & Prevent Unnecessary Burdens.

In exploring the merit of such a motion in accord with the reasonableness test in National Grocers Co Ltd., the statutory scheme is considered;

-

Rule 90.30(6): An appellant must file an electronic copy of the transcript in a format satisfactory to the registrar, in addition to filing paper copies, unless the registrar or a judge of the Court of Appeal orders otherwise.

-

Rule 90.30(5): A party may make a motion to a judge of the Court of Appeal for an order abridging a requirement for the form or content of the appeal book.

-

Rule 1.01: These Rules are for the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every proceeding.

By way of the schema, the court is sensitive to the onerous burden that might be imposed by way of the printing, binding, handling, and shipping costs of the five Appeal Books. Rule 90.30(6) states that a judge may make an order to waive filing five hardcopies. Rule 90.20(5) states that a party may make a motion to abridge a requirement for the form or content, being the same. As such, a motion to waive the customary paper filing requirement was lawfully made in accordance with the statutory scheme.

The next rule to consider is 1.01, which informs the court on how the rules must be interpreted and applied. Because the permanent confidentiality order being appealed concerns the entire file, the Appeal Book contents cannot be truncated without compromising the effect of the Appeal (Rule 90.30(4)). Forty (40) bound paper volumes amounting to 13,205 pages, plus service fees, binding, and delivery expenses pushed costs for the print job well north of $2,000 CAD for the Appeal of a lower court decision that was disposed at $500 all-inclusive. As such, a motion to mitigate these costs by questioning the utility of the printed hardcopies has merit.

The chain of analysis must then turn to the actual utility of the printed hardcopies. Ie., will reproducing the lower court file again in hardcopy solve a problem; would the appellate panel make use of the printed hardcopies; and will the absence of the printed hardcopies be a burden?

Beyond the ruleset, contributing materials include the court's e-filing practice directive, and the March 19th, 2025 written directive of the Registrar that was issued to the Parties. Both of these documents suggest that searchable PDF files are preferred by the appellate panel as opposed to paper filings, and are expected to be relied upon at the actual hearing. This makes sense because paper volumes in this order of magnitude would require the court to pause the hearing to sift through a mountain of cerlox binders to locate a specific references they could otherwise find in a few keystrokes through an electronic keyword search. Finally, the 40 bound volumes would require storage space in a court that houses thousands of other cases on file, and whereas, the same documents are already filed in hardcopy in the same building. The balance of convenience thus favors a reliance on electronic filing.

Thus in summary, the motion was allowed by the rules. The motion was encouraged by the rules. The motion could be filed ex parte (Rule 22.03(1)(a)), because the order sought had no impact on the CAGE, who had relied on PDF copies since inception. Granting the motion would not impact the court negatively in its ability to adjudicate the appeal because it could rely on the same materials in electronic format (as it always had during Covid). Granting the motion would impact the court positively by reducing the carbon footprint and storage space. Finally, granting the motion would not impact the CAGE Respondents one way or the other. Having established all of this, an unbiased observer aware of this would conclude, very reasonably and objectively, that a motion like this can expect to be granted. As a result of this analysis, I filed the motion.

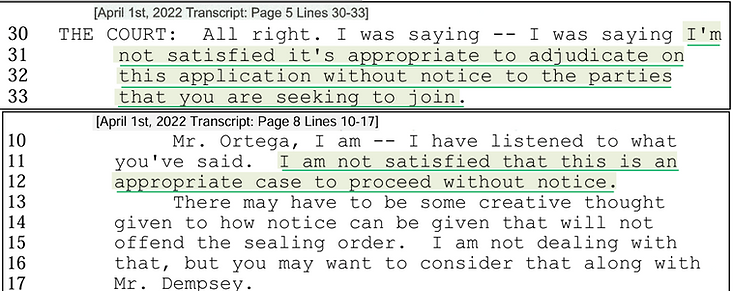

The Court Waived the Ex Parte Rule, Ordered a Contested Hearing, & Dismissed the Motion.

Per the image below, the court issued a response to my correspondence motion three days after it was filed, to the extent that the consensual ex parte motion for e-filing, would be set down as a contested chambers hearing. This was an irregularity, as Rule 22.03 expressly states that motions can be filed ex parte if the relief sought has no impact on any other person. As it was, the motion had asked the court to rely on the same electronic format the CAGE had always used. The court's letter likewise suggested that the Appeal Book be truncated, which would weaken the essence of the Appeal. In a de facto manner, the same letter had telegraphed the position the judge would be adopting.

Per the image that follows, CAGE counsel advised that they still had no intention to contest the e-filing motion, but advised that they would not consent to it. Whereas there appears to be no nuanced legal definitions at stake, the statement is an oxymoron. In the same email, the CAGE admits that the print job was expected to be an “significant burden”. It must be noted that the motion sought the mitigation of paper filings in their entirety; not that the responsibility for filing hardcopies be transferred to the CAGE.

The judge cut me off mid-sentence at the onset of the chambers hearing when I had introduced submissions concerning the ex parte Rule. Shortly thereafter, the judge dismissed the e-filing motion and provided three oral reasons. Namely;

-

That the court had no secure e-filing “system” in place (in other words, the court could not accept e-filed documents);

-

That I could only make an assumption concerning the appellate panel’s preferences concerning file formats (ie., keyword search capability vs. having to sift through boxes and binders), and finally;

-

That I did not prove I was impecunious, and therefore, I must pay for the print job, regardless of whether or not there was any merit or utility in doing so, and, irrespective of how the cost of the print job could have been otherwise allocated. At the time of the hearing, the cost of the unnecessary print job was comparable to the cost of purchasing six months of groceries.

The court's reasons don’t make any sense, obviously. Concerning points (a) and (b), the court had a published an e-filing directive, and the motion was based in the statutory scheme. Likewise, the Registrar’s directive had insisted that the parties file their documents electronically, and had indicated of the habits and preferences of the reviewing panel. Concerning point (c), a state of impecuniosity or lack thereof is immaterial by way of the foregoing substance, and in view of the guiding principle outlined in Rule 1.01 concerning the mitigation of unnecessary costs.

The test in National Grocers is expanded upon in JE and KE v. Children’s Aid Society of the Niagara Region (Div Ct, 2020) at paragraphs 39, 40;

“Reasonableness, of course, finds its starting point in judicial restraint and respects the distinct role of administrative decision-makers. The Vavilov approach focuses on justification and methodological consistency because “reasoned decision-making is the lynchpin of institutional legitimacy” (para. 74). Thus, reasons are the “primary mechanism by which administrative decision makers show that their decisions are reasonable” (para. 81). For this reason, a reviewing court must begin its inquiry into the reasonableness of a decision by examining the reasons. A reasonable decision is one that is based on an internally coherent and rational chain of analysis and that is justified in relation to the facts and law that constrain the decision-maker. It is not enough for the outcome of the decision to be justifiable. The decision must also be justified by way of the reasons. An otherwise reasonable outcome cannot stand if it was reached on an improper basis (para.86).”

It should likewise be noted that the out-of-province venue, much like the BC court has refused to acknowledge any of the aspects of the scandal, or their effects, irrespective of the fact that they are clearly outlined in my filed Affidavits, and likewise the filed Affidavits of the CAGE.

Does the Court's Dismissal of the E-Filing Motion Express Bias?

In its own right, the decision was unreasonable by way of the test in the foregoing case law. Considered independent of the remainder of the scandal, an argument could be made that perhaps, an unknown member of the appellate panel might prefer to review paper documents. Yet, that premise is overshadowed by the overarching statutory scheme, the e-filing directive, the Registrar’s directive, and the fact that the initial consensual ex parte motion was transitioned into a contested hearing without any reasonable explanation. The operations of the court during the covid pandemic, which relied exclusively on electronic filings, is another data point. These factors contribute to a reasonable apprehension of bias, albeit the outcome may not occasion an irregularity that would shake public confidence in the institution if the motion were considered as an independent object (R. v. Tayo Tompouba, 2024 SCC 16 at paragraph 72).

However, when understood in the context of the overarching scandal, and whereas the issues detailed on this page are peanuts compared to those outlined in the Civil page (and franky, the remainder of the website), the onerous and unreasonable outcome of the e-filing motion can be considered another plank in the wobbling jenga tower the overarching scandal represents. This is underscored by the conduct of the same judge in the two other motions she presided over, as is detailed in the next two sections below.

Runaway Security-for-Costs as a Procedural Hurdle.

An Extreme Departure From the Case Law.

The CAGE brought a motion to require me to post security of costs, or in other words, pay any costs the CAGE might incur in the Appeal before the Appeal is heard. The use of this litigation tool, being regularly employed but considered controversial in certain circumstances, is guided by a series of legal tests in the jurisprudence. The tests concern the following questions;

-

Should an order for an Appellant to post security for costs be made?

-

If an order is granted, how much money should be paid up-front?

-

What happens to the Appeal if the money is not paid on time?

In the same Appeal concerning the unconstitutional confidentiality order, the CAGE requested, and was granted, a security of costs order with a payment quantum of $8,000. This amount was required to be paid within ten (10) days of the order that was made the same day, or the Appeal would be automatically dismissed. All of these characteristics are exceptional outliers as compared to the case law.

The first legal test concerning a motion for security for costs concerns the feasibility of the request with respect to the merit in the Appeal. This makes sense because it is obvious that an appeal that is expected to be successful would not result in any monies paid out to the opposing party. If an expectation of success in the Appeal is not overtly obvious, the test concerns an Appellant’s ability to pay money up-front, in the understanding that such money may eventually be awarded to the respondent party. The test requires a court to review all of the circumstances of the case, and all issues that might be related. Per Yaiguaje v. Chevron Corporation, 2017 ONCA 827 at paragraph 15;

“In so ruling, the motion judge found that the appellants had not established that they were impecunious or that third party litigation funding was unavailable. Because she found that impecuniosity had not been established, the motion judge ruled that the appellants had to demonstrate that their claim has a good chance of success.”

Likewise at paragraphs 18 & 19;

“In an appeal, there is no entitlement as of right to an order for security for costs. Even where the requirements of the rule have been met, a motion judge has discretion to refuse to make the order: Pickard v. London (City) Police Services Board, [2010] O.J. No. 4169, 2010 ONCA 643, 268 O.A.C. 153, at para. 17. In determining whether an order should be made for security for costs, the "overarching principle to be applied to all the circumstances is the justness of the order sought": Pickard, at para. 17; and Ravenda Homes Ltd. v. 1372708 Ontario Inc., [2017] O.J. No. 3414, 2017 ONCA 556, at para. 4.”

Finally at paragraph 25;

“The correct approach is for the court to consider the justness of the order holistically, examining all the circumstances of the case and guided by the overriding interests of justice to determine whether it is just that the order be made.”

The statutory scheme follows the same pattern. Rule 90.42(1) requires that an order to post security should only be made if the court considers it just. This follows Rule 45.02(1)(d), which states that a judge may only order security for costs if in all the circumstances, it is unfair for the claim to continue without it.

With respect to the Appeal detailed in the foregoing sections, concerning an unconstitutional confidentiality order over the entirety of a file (all 2,640 pages), and given the case law and Affidavit detailed on the Censorship II page (here), success in this appeal is all but certain under normal conditions. The weight of settled Constitutional law underscores this. Having established that, the case law maintains that no order to post security should be made, as such an order would suggest that a Citizen’s rights under the Charter are subject to privilege.

The court did make the order, as is shown below the text. This is important, as it assumes the Appeal is expected to fail, and that the unconstitutional censorship of the scandal will remain, as it had for the past three years. We must now direct consideration to sections (b) and (c) of the test criteria, which consider the quantum (or amount) of payment to be made up-front, and the effects of non-compliance within the timetable ordered. A reliable quantum test is shown in Power v. Power, 2013 NSCA 137, which cites a "40% of lower court costs" rule at paragraphs 27-29, with the court requiring 60 days to pay (at paragraph 30);

“It is frequently said that party and party costs on appeal are 40 percent of the costs awarded in the lower court. An award of costs is always a discretionary one, to be decided by the panel who hears the appeal. [...] Barkhouse v. Wile, 2011 NSCA 50 and Kedmi v. Korem, 2012 NSCA 124; Richards v. Richards, 2012 NSCA 7; St.‑Jules v. St.‑Jules, 2012 NSCA 97; Dunnington v. Emmett, 2012 NSCA 55; Campbell v. Campbell, 2012 NSCA 86; and Blois v. Blois, 2013 NSCA 39. [...] I would note that in Blois v. Blois, my colleague, MacDonald, C.J.N.S. ordered 40 percent of the trial costs ($7,500) in arriving at the security of costs award of $3,000.”

The straightforward confidentiality motion being appealed was disposed of at $500. By way of the test in Power v. Power, a reasonable quantum of security would be $200. Instead, the court ordered $8,000 - the same being sixteen (16) times the cost of the lower court matter.

If the foregoing two data points do not elicit a reasonable apprehension of bias, the terms of the order most certainly will. As is shown in the image below, the court required the money to be paid within ten calendar days to avoid the automatic dismissal of the appeal. That clause essentially exposes a the right of appeal, and the right to seek relief concerning a Constitutional matter, to any manner of extraneous events that could occur between the date of the order and the deadline. A car accident, for example, could prevent payment on time, and the appeal would be automatically dismissed as a result.

There is no provision in the statutory scheme or case law that permits the automatic dismissal of an appeal as a result of a failure to post security within the deadline of the order. Rule 90.42(2) requires a motion to be filed for dismissal, upon failure of payment;

“A judge of the Court of Appeal may, on motion of a party to an appeal, dismiss or allow the appeal if the appellant or a respondent fails to give security for costs when ordered”.

The same principle is clearly outlined in the jurisprudence. Per Dataville Farms Ltd. v. Colchester County (Municipality), 2014 NSCA 95 at paragraphs 17 and 19 as follows:

"The respondents assert that the appellant has failed to comply with this Court’s order to give security for costs and as such, the appeal should be dismissed. They acknowledge that dismissal is not automatic in the face of such a failure, but submit that a heavy onus should lie upon a defaulting appellant to convince the Court that the appeal should be permitted to continue. [...] At this juncture it may be of assistance to make some general observations. Firstly, the remedy sought by the respondents - dismissal of the appeal due to failure to provide security for costs, is, in accordance with Rule 90.42(2), discretionary. It should not be presumed that an order for dismissal will automatically flow from an appellant’s failure to abide by an order to give security."

The same case law detailed the procedural process for disposing Appeals on a finding of non-payment of security at paragraphs 23-25 and 35;

“The appellant relies upon four decisions in support of his contention that dismissal of the appeal would be inappropriate. With respect, none are of assistance. Three clearly relate to the appropriateness of security for costs in the first instance (Blois v. Blois, 2013 NSCA 39; S.U. v. Family and Children’s Services of Yarmouth County, 2005 NSCA 76; and Disabled Consumer Society of Colchester v. Burris, 2009 NSCA 21), and the fourth appears to be a divorce proceeding, with no applicability at all to the matter before the Court. Mr. Self argues that to terminate an appeal is, as stated by Justice Cromwell, “extraordinary” and should be a measure of last resort. [...] I agree that dismissing an appeal is “extraordinary” given the finality of that decision. I do not, however, interpret MacDonald, supra, as standing for the proposition that the Court should shy away from dismissing an appeal for failure to post security for costs in appropriate cases. [...] Once it is established by evidence that an appellant has failed to abide by an order requiring the posting of security for costs, in my view, the onus then shifts to the appellant to provide compelling reasons why dismissal is not in the interests of justice. [...] There may be instances where an appellant fails to comply with an order to post security for costs, yet is able to satisfy the Court that the interests of justice require the appeal to continue.”

It is terrifying that a Federally-appointed judge would act in a manner to obstruct a Citizen’s constitutional rights, and likewise, subject these same rights to any manner of extraneous factors that may or may not have anything to do with the proceeding, with the support of the Attorney General's office. The section below this details an account where the same judge violated the open court principle yet again in a consensual motion for redaction, which kept the file entirely sealed while the SCC docket was pending (and likewise, whereas the SCC registry had violated its own rules in delaying the motions I had filed to stay the cost scandal).

$8,000 in Security (40 x the Power v. Power Test) to Appeal the Unconstitutional Sealing Order.

And Another $8,000 in Security (40x the Power v. Power Test) to Appeal the Contempt Declaration.

Censorship of the Appellate File

The Confidentiality Order Shenanigans Continue.

A Procedural Sleight-of-Hand

On April 24th, 2025, a judge placed a confidentiality order over the lower court contents being appealed, the entirety of a 2,640-page file, as referenced above, in effect until further court order. The oral order, shown below in the transcript, was not reduced to paper.

On May 1st, 2025, the CAGE obtained an overlapping interim confidentiality order from the Registrar that had enacted the same effects, and filed a motion seeking the exact same relief as the April 24th order; that the sealed materials under appeal would remain sealed in the Appeal files until their hearing. That motion was initially scheduled for May 22nd, 2025, but was heard on June 5th, 2025 instead. As innocuous as that might seem, the filing of the CAGE duplicate motion had triggered NS Civil Procedure Rule 90.37(15), which states, “on motion, a judge of the court of appeal may make an order to (c) require a sealing of a court order, until the court of appeal provides a further order”. Thus, at the June 5th hearing, the presiding appellate judge had an option to defer the motion to a 3-judge appellate panel. She acted on that jurisdiction, thereby extending the duration of the duplicate interim confidentiality order over the appeal files for another five months.

Here is the catch. While the effects of April 24th order and the June 5th motion deferral are the same, the difference is that the duplicate interim sealing order included a large quantity of additional materials under its umbrella that were not filed in the lower court, or in any court prior, being newly introduced on April 28th, 2025. These materials do not qualify for an exception to open court. They include the BCSC clerk’s notes showing the nine (9) short-chambers hearings that the $400,000 cost scandal was predicated on (here), my recent discussions with the NS Police Complaints Commissioner concerning unaddressed and related criminal issues, and proof that the NS court had published a revisionist narrative regarding the contents of the sealed lower court file (here). These materials, sealed by way of a Registrar’s interim order, and later deferred by the motion judge relying on a procedural rule that was triggered by the redundant CAGE motion, concern issues that were directly relevant to the substance of a motion for a stay and injunction. That motion rested on the test in RJR MacDonald Inc. v. Canada (AG) (1994) 111 DLR (4th) 385, [1994] 1 SCR 311, which asks whether there are serious questions to be tried, and if a Party will suffer irreparable harm. In summary, the redundant CAGE motion gave the court a procedural excuse to seal incriminating evidence that does not qualify for a confidentiality order.

The visuals below outline the chain of events just described.

April 28, 2025: The Deputy Registrar Seals my New Affidavit, and I File a Motion for Modest Redaction.

April 29th, 2025: A Written Order Issues for the April 24th Hearing that Omits the Oral Sealing Order.

May 1st, 2025: CAGE Files Motion to Duplicate the Unlisted April 24th Order. Registrar Seals Entire File.

June 5th, 2025: The Judge Seals New Material Using a Procedural Loophole, Triggered by CAGE Motion.

The Procedural Loophole via Rule 90.37(15)(c) Gave the Judge a Discretionary Choice...

...But Not a Mandate to Seal New Materials that Don't Qualify for a Confidentiality Order.

Besides the foregoing procedural sleight-of-hand, it should still be noted that Rule 90.37(15)(c) is a discretionary procedural rule. Procedural rules are subservient to substantive law in the jurisprudence;

Somers v. Fournier, 2002 CanLII 45001 (ON CA) at paragraph 14;

“This court has described the distinction between substantive and procedural law in these terms: Substantive law creates rights and obligations and is concerned with the ends which the administration of justice seeks to attain, whereas procedural law is the vehicle providing the means and instruments by which those ends are attained. It regulates the conduct of Courts and litigants in respect of the litigation itself whereas substantive law determines their conduct and relations in respect of the matters litigated.”

Sutt v. Sutt, 1968 CanLII 221 (ON CA);

“What I have stated as to the desirability that rules of procedure should be flexible applies with equal force to their application in particular circumstances having special regard to the substantive right which the litigant may be invoking. It would be inappropriate to apply a rule so rigidly in certain instances as to lead to a denial rather than an affirmation of right and justice. [...] The rule must be so construed and applied as not to create a conflict between it and the substantive law created by the Act to which the Rules are necessarily subservient."

The Open Court mandate, elucidated in the Constitutional tests (here), and cited at NS Rule 85.04(1) in limiting the discretion of a judge, is substantive law. Rule 90.37(15)(c) gave the motion judge the option to defer the redundant CAGE confidentiality motion to the 3-judge panel at her discretion, if doing so would further the object of justice. No oral or written reasons were provided. The contempt proceedings, which could result in incarceration, remain unstayed, and precluded from public view. It is worth noting the following test as it applies here:

R. v. Tayo Tompouba, 2024 SCC 16 at paragraph 73;

“Courts have found a miscarriage of justice in a wide range of circumstances (see A. Stylios, J. Casgrain and M.‑É. O’Brien, Procédure pénale (2023), at paras. 18‑87 to 18‑81). Examples of a miscarriage of justice include the ineffective assistance of counsel (see White), a breach of solicitor‑client privilege by defence counsel (Kahsai, at para. 69, citing R. v. Olusoga, 2019 ONCA 565, 377 C.C.C. (3d) 143) and a misapprehension of the evidence that, though not making the verdict unreasonable, nonetheless constitutes a denial of justice (R. v. Lohrer, 2004 SCC 80, [2004] 3 S.C.R. 732, at para. 1; Coughlan, at pp. 576‑77). Unfairness resulting from the exercise of a “highly discretionary” power, related to proceedings leading to a conviction and attributable to a judge will also generally be analyzed under the miscarriage of justice framework (Fanjoy, at pp. 238‑39; Kahsai, at paras. 72 and 74).”

It must be noted that court files pertaining to the scandal had remained unconstitutionally sealed at all times since inception, including in extrajudicial circumstances (here), and in cases where the court itself had undertaken a unilateral order that the Parties did not seek (here).

Addressing the Scandal

The Court Ignored Proof of Scandal, Questioned My Integrity, and Positioned the CAGE as the Victim...

...in an Environment of Secrecy.

As denoted above, I had recently encumbered over $20,000 to participate in the appeal of an unconstitutional blanket sealing order, and a civil contempt hearing, which arose as a result of my continued opposition to a $400,000 execution order predicated on retainer fees for just nine short-chambers hearings (here). The same dollar amount likewise exceeds my remaining savings, and a contempt punishment hearing could land me in jail. I have been without income since November 2021, when the related criminal interference began manifesting (here). The prospect of subsequent incarceration in a contempt punishment hearing further raises the autoimmune health concerns introduced by the first instance in 2024 (here). All of these demonstrate that an earnest problem was brought before the court.

Yet, in the wake of posting security for costs as described in the previous section (16 times the lower court fees), I was characterized by an appellate judge as appealing the contempt order in bad faith. This is shown in the decision excerpts below. The decision text quotes a series of case law examples, though Ewert v. Penny, 2024 NSCA 104 at paragraph 6 provides the most concise operative definition of the "clean hands" descriptor used;

“There is also another reason I would refuse a stay. A stay is an equitable remedy which requires the party seeking it to come to the Court acting in good faith. I find that Mr. Ewert is using the court process for an improper purpose – to cause Ms. Penny undue hardship. He has not come to the Court with clean hands, as that term is known in law, and, for that reason alone, I would refuse the equitable remedy of a stay.”

In response to an "improper use of court" allegation, I would ask how else might I be able to address the issues described above, if not through the court? A whistleblower has not yet emerged. These comments further indicate a persistent trend in rejecting the fact matrix of the scandal, as again referenced below in the judge's refusal to address the contents of my detailed briefs concerning them (here).

Slatter J. distinguished honest errors in Jonsson v Lymer, 2020 ABCA 167 at paragraph 14, as they might apply, albeit NS Rule 90.37(2) & 90.48(1)(e) clearly equipped the enforcement court to provide the stay and injunctive relief sought in the motion (again, see briefs here). Per Slatter J.;

“Vexatious litigants must be distinguished from self-represented litigants. Merely because a self-represented litigant uses a process that is not in accordance with the Rules of Court, or advances a claim without merit does not mean that they are vexatious. Many self-represented litigants are unfamiliar with court procedures, and are inadequately or inaccurately informed about their legal rights and the limitations on them. Merely because the self-represented litigant excessively or passionately believes in the merit of his or her cause does not make them vexatious.”

The Court Refused to Acknowledge a Fact Set Predominantly Proven in the CAGE Affidavits.

"To comply with s. 7 of the Charter, the magistrate must make a decision based on the facts and the law." - Charkaoui v. Canada (CI), [2007] 1 S.C.R. 350, 2007 SCC 9 at paragraph 48

A reasonable apprehension of bias is again underscored by way of the fact that the enforcement court had violated Constitutional law and manipulated its processes to consistently kept the file sealed (the next section below and again here), and had posted revisionist narratives concerning the factual matrix of the same files, as denoted earlier in the page. In every instance, these reasons position previous orders concerning the parties as correct and legitimate, and position the CAGE as the victim of meritless proceedings while ignoring the incriminating Affidavits that their CEO and lead counsel had sworn, in addition to the proofs of related interference that was likewise before the court.

The same trend is expressed through reasons shown below, which assume that past adjudications were entirely legitimate. Magee (Re), 2020 ONCA 418 at paragraphs 19, 20, quoting the SCC in Canada (CI) v. Vavilov, maintains;

"A reasonable decision is one that, having regard to the reasoning process and the outcome of the decision, properly reflects an internally coherent and rational chain of analysis: Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, 441 D.L.R. (4th) 1, at paras. 102-104. In addition, a reasonable decision must be justified in relation to the constellation of law and facts that are relevant to the decision. For instance, the governing statutory scheme and the evidentiary matrix can constrain how and what an administrative decision-maker can lawfully decide. Further, “[w]here the impact of the decision on an individual’s rights and interests is severe, the reasons provided to that individual must reflect the stakes”: Vavilov, at para. 133. The principle of responsive justification means that especially in such high-stakes cases, the decision maker must meaningfully explain why its decision best reflects the legislature’s intention. A Board’s disposition will be unreasonable if the underlying reasons cannot bear even a somewhat probing examination: R. v. Owen, 2003 SCC 33, [2003] 1 S.C.R. 779, at para. 33."

The astute reader will recognize that when the effects of a scandal survive in the wake of court proceedings that were intended to address them, something is wrong. The effect is exacerbated when a growing footprint of evidence shows that a court had a hand in facilitating those effects, and when the wrong orders remain in the wake of recourse via appeal or certiorari.

Proof that the BC Courts had miscarried a shareholder scandal are shown in the records presented (here), and the same is true concerning the cost certification that followed (here). A reasonable litigant does not encumber a $400,000 retainer in support of nine thirty-minute hearings with modest prep, which were often handled by articling students. When a law firm deigns to claim in an Affidavit that those fees were reasonably required (here at paragraph 10), and when courts certify and enforce it at face value, a scandal is evidenced that would necessarily require assurances from an efficacious third-party. The scandal need not be demonstrated by way of a failed appellate recourse - the scandal is evidenced in the fact that it had happened to begin with. There is extreme risk in facilitating a felony through recognized institutions, and there would be numerous risk-laden boxes to tick. Reasonable persons can ask a series of questions, such as those following;

Who assured Osler, Hoskin, & Harcourt LLP to swear an outrageous Affidavit concerning the CAGE retainer? Why might the CAGE CEO agree to a $400k retainer that should cost $4,500? Who had assured the BC adjudicator in signing the certificates that had so exorbitantly violated case law and common sense? Who had assured the adjudicators in their S-220956 actions cited (here)? Who had encouraged BCSC registry staff to ignore nine key procedural rules in S-229680? Who had assured the BCCA Registrar in certifying a certificate for one short hearing at 89.9 billable hours, or $45,000 (whereas Rosinski J.A. had adjudicated a near duplicate for $500). Who had assured the same Rosinski J.A. to make a false statement concerning the BC proceedings, which three Appellate court judges had agreed with several months later? Who assured SCC Registry Officers to violate SCC Rule 54(4) in keeping my stay motions derelict, while Van den Eynden J.A. violated Constitutional law to keep the NSCA file sealed concurrently in 2023? Who had advised BCSC staff that they could seal S-229680 prior to a court order or hearing, and prior to the CAGE accepting service (here)? Who prompted the RCMP to deny safe avenue in Surrey, BC, and who had prompted a well-meaning HRP police constable to file a false report after he had acknowledged the CAGE CEO in relation to the related criminal elements in a 79-minute meeting, and had outlined steps for an investigation? The list goes on, and on, and on.

These effects and many others generate an appearance of unfairness that is capable of shaking public confidence in the institutions and agencies involved (R. v. Cameron (1991), 1991 CanLII 7182 (ON CA), 64 C.C.C. (3d) 96 (Ont. C.A.) at page 102; R. v Wolkins, 2005 NSCA 2 at paragraph 89; R. v. Davey, 2012 SCC 75, [2012] 3 S.C.R. 828 at paragraphs 51, 87; R. v. Tayo Tompouba, 2024 SCC 16 at paragraph 54; R. v. Kahsai, 2023 SCC 20 at paragraphs 67-68). The lower court judge took none of this into consideration in her contempt declaration, and neither did the appellate motion judge in rejecting a stay of proceedings. None of the above mattered, as measured against an interest in obeying an oppressive mandate on pain of incarceration and/or bankruptcy.

When comments are made to the effect that there is no patent injustice involved, or no errors of fact, law, or mixed fact and law apparent, the adjudicators making them are patently disingenuous. The evidence is right there before them. Likewise, as was detailed in my "decision-tree brief" (here), if these facts are acknowledged, and I am asked to be incarcerated for opposing the effects of the same scandal in the absence of corrective measures, that too is a miscarriage of justice per the case law below. Suggesting that a victim is the author of his own destruction by refusing to comply with a felony shows utter disregard for Constitutional supremacy. I have been asked to choose between being the bankrupt victim of a neurotech privacy crime, and oppressive contempt actions that may lead to an early grave if I am incarcerated at any length. The file remains sealed so the public cannot grasp an obvious scandal. There is sufficient evidence to conclude that the courts have acted in solidarity.

Colburne v. Frank, 1995 NSCA 110 at paragraph 9;

"...Under these headings of wrong principles of law and patent injustice an Appeal Court will override a discretionary order in a number of well‑recognized situations. The simplest cases involve an obvious legal error. As well, there are cases where no weight or insufficient weight has been given to relevant circumstances, where all the facts are not brought to the attention of the judge or where the judge has misapprehended the facts. The importance and gravity of the matter and the consequences of the order, as where an Interlocutory application results in the final disposition of a case, are always underlying considerations. The list is not exhaustive but it covers the most common instances of appellate court interference in discretionary matters. See Charles Osenton and Company v. Johnston (1941), 57 T.L.R. 515; Finlay v. Minister of Finance of Canada et al. (1990), 1990 CanLII 12961 (FCA), 71 D.L.R. (4th) 422; and the decision of this court in Attorney General of Canada v. Foundation Company of Canada Limited et al. (S.C.A. No. 02272, as yet unreported). [emphasis added]"

R. v Wolkins, 2005 NSCA 2 at paragraph 89;

"The clearest example is the conviction of an innocent person. There can be no greater miscarriage of justice. Beyond that, it is much easier to give examples than a definition; there can be no “strict formula .. to determine whether a miscarriage of justice has occurred”: R. v. Khan, 2001 SCC 86 (CanLII), [2001] 3 S.C.R. 823 per LeBel, J. at para. 74. However, the courts have generally grouped miscarriages of justice under two headings. The first is concerned with whether the trial was fair in fact. A conviction entered after an unfair trial is in general a miscarriage of justice: Fanjoy supra; R. v. Morrissey (1995), C.C.C. (3d) 193 (Ont. C.A.) at 220 - 221. The second is concerned with the integrity of the administration of justice. A miscarriage of justice may be found where anything happens in the course of a trial, including the appearance of unfairness, which is so serious that it shakes public confidence in the administration of justice: R. v. Cameron (1991), 1991 CanLII 7182 (ON CA), 64 C.C.C. (3d) 96 (Ont. C.A.) at 102; leave to appeal ref’d [1991] 3 S.C.R. x."

Perka et al. v. The Queen, 1984 CarswellBC 2518, at paragraph 96;

“This, however, is distinguishable from the situation in which punishment cannot on any grounds be justified, such as, the situation where a person has acted in order to save his own life. As Kant indicates, although the law must refrain from asserting that conduct which otherwise constitutes an offence is rightful if done for the sake of self-preservation, there is no punishment which could conceivably be appropriate to the accused's act. As such, the actor falling within the Chief Justice's category of "normative involuntariness" is excused, not because there is no instrumental ground on which to justify his punishment, but because no purpose inherent to criminal liability and punishment — i.e., the setting right of a wrongful act — can be accomplished for an act which no rational person would avoid.”

Canadian Broadcasting Corp. v. Named Person, 2024 SCC 21 at paragraph 1;

“When justice is rendered in secret, without leaving any trace, respect for the rule of law is jeopardized and public confidence in the administration of justice may be shaken. The open court principle allows a society to guard against such risks, which erode the very foundations of democracy. By ensuring the accountability of the judiciary, court openness supports an administration of justice that is impartial, fair and in accordance with the rule of law. It also helps the public gain a better understanding of the justice system and its participants, which can only enhance public confidence in their integrity. Court openness is therefore of paramount importance to our democracy — an importance that is also reflected in the constitutional protection afforded to it in Canada.”

Value(s): Building a Better World for All [Link] Mark Carney, 2021, ISBN 0008485240, P. 95, 494;

“Magna Carta was a desperate and probably disingenuous attempt at a peace treaty that failed almost immediately. Brokered by the Church, and issued by King John in June 1215, the Charter sought to placate the disgruntled barons. [...] If Magna Carta was such a product of its time, how did it become to be so venerated? And once we cut through the legend, what is its significance for economic governance today? [...] The world is being reset. Now we are on the cusp of what some have called a Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Applications of artificial intelligence are spreading due to advances in robotics, nanotechnology and quantum computing. Our economies are reorganising into distributed peer-to-peer connections across powerful networks – revolutionizing how we consume, work and communicate. Solidarity will determine the success of the 4IR, where the need for new institutions that live the value of solidarity is the greatest.”

See citations by Michel Foucault & Dr. Colin Crouch at the politics page (here), in an exploration of post-democratic characteristics.

The Court Would Sooner Gamble My Physical Health Than Acknowledge a Patent Injustice.

A False Dilemma

Per the excerpts below, the appellate motion judge denied the existence of related criminal interference and the neurotech component, which satisfy tests for reasonable grounds as outlined (here, here, & here). Moreover, the judge made light of a serious health condition triggered during my August 2024 incarceration period that is expected to result in liver failure if prolonged.

Evidence of the autoimmune health condition was before the contempt motion judge on April 1st, 2025, who had pre-drafted her decision prior to the hearing. Likewise, officials at the prison were informed of my dietary requirements upon entry. Whereas just ten parts-per-million of gluten per day will trigger internal damage, shared kitchen surfaces and airborne particles can achieve that threshold in an otherwise controlled dietary regime. The appellate motion judge, in her decision, offers a false dilemma (Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, [2019] 4 S.C.R. 653 at paragraph 104), as a purge of contempt would elicit effects not dissimilar to the effects of a failed opposition.

While an incarceration may invariably result in life-threatening health complications, compliance with the effects of the scandal would result in a fate worse than death. In the absence of correction, the effects of this scandal will result in tent-city life, devastated career prospects, an ongoing neurotech privacy violation, unresolved trauma, and a concession of core beliefs and ethical standards. In Perka at page 246, Dickson J. would agree that this would place “an intolerable burden on the accused”. Iacobucci J. held in Syndicat Northcrest v. Amselem, [2004] 2 S.C.R. 551, 2004 SCC 47 at paragraphs 40, 41 that “Freedom means that no one is to be forced to act in a way contrary to his beliefs or his conscience”. Notwithstanding these unsavory options, the judge refused to consider the third option before her - to recognize that a scandal had been facilitated through legitimate authorities, that triggers the "patent injustice" case law she cited earlier in the text. Again, an assertion that I would author my own demise is disingenuous. Per my Testimony (here), and Factum (here), I did not initiate the scandal, or fail to avail myself of a feasible exit ramp. Likewise, I did not act as Deponent in the CAGE Affidavits (here & here), nor did I fabricate this, this, or this, and I could not if I wanted to. I am compelled to post this online because the file is unconstitutionally sealed, and my life is imperiled.

"There is Only the Enforcement"

A Request to Stay the Proceedings & Stop the Destruction.

The June 2025 hearing before appellate judge Anne S. Derrick considered two components; (1) the sealing of the appellate file as referenced above in the previous section; and (2), a motion to stay the proceedings to prevent the enforcement of a felony, and prevent any penalties that might be imposed for opposing it. The request included injunctive relief to preclude future enforcement attempts. Three detailed case law briefs in anticipation of the hearing, including its compelling questions and issues, are shown (here). The motion to stay the contempt proceedings and permit injunctive relief was dismissed.