Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act (S.C. 2000, c. 24) [Link]

Access to Justice

Criminal Interference | Denial of Recourse | Obstruction of Justice | Abuse of Process | Miscarriage of Justice | Censorship

A Framework of Third-Party Influence

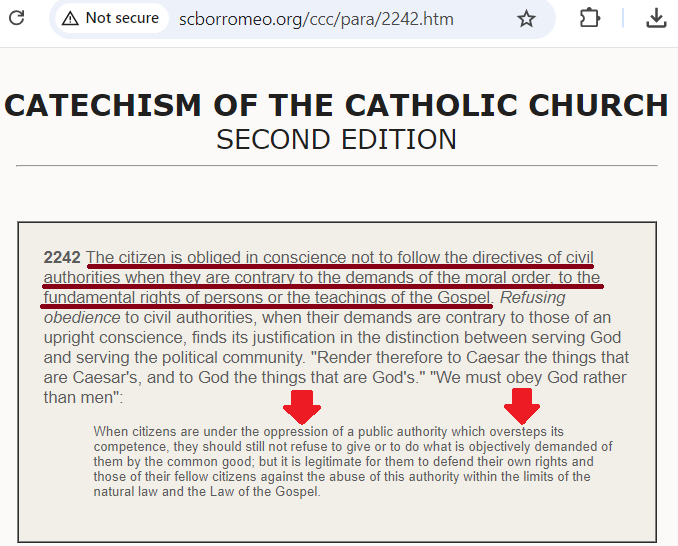

Materially related to the Zersetzung accounts, a prima facie case of shareholder fraud concerning the Director of a Canadian Commercial and Government Entity ("CAGE") was reversed into a $445,489.50 award of special costs to the perpetrator. This disposition remained unchecked despite Canadian Constitutional Law and jurisprudence. The scope, consistency, and characteristics of this scandal, involving multiple courts and police agencies across three provinces, precludes consideration of the CAGE Director as an independent perpetrator. Because one CEO cannot disrupt a country's justice system to this extent, an inexorable inference of third-party tampering is occasioned.

FIFTY Social Influencers | FIVE Courts | THREE Police Agencies | ONE Scandal

An Encyclopedia of Obstruction:

The Scandal as it Pertains to the Courts

ABSTRACT

This multi-section page examines a four-year pattern of coordinated institutional dysfunction across Canadian judicial, law enforcement, and regulatory bodies that cannot be adequately explained through conventional theories of judicial error, administrative oversight, or individual malfeasance. Various sections are treated in more detail through the sub-menu links above, and via the table of contents (here). Drawing on comprehensive documentary evidence spanning British Columbia and Nova Scotia courts, RCMP, regulatory agencies, and multiple levels of the judiciary (2021-2025), the analysis demonstrates systematic deviation from binding constitutional and procedural authorities—not episodically, but coordinately across independent institutions with no formal mechanism for such coordination. The pattern exhibits characteristics consistent with what political theorists term "post-democratic governance": institutions retain constitutional forms while operational decision-making serves objectives external to their formal mandate. This case study provides empirical validation of theoretical frameworks proposed by Wolin, Rancière, and Foucault regarding how democratic institutions can be instrumentalized for extra-legal purposes while maintaining legitimating facades. The implications extend beyond individual injustice to fundamental questions about constitutional supremacy in an era of technological surveillance, networked coordination, and Fourth Industrial Revolution capabilities that enable governance modalities incompatible with classical liberal constitutionalism.

Keywords: Post-Democratic Governance, Institutional Coordination, Constitutional Supremacy (s.52), Open Court Principle, Vavilov Reasonableness, Beals v. Saldanha Enforcement, Abuse of Process, Access to Justice, Discovery Inversion, Summary Judgment Acceleration, Use of Discretionary Power, Prohibitive Security Orders, Institutional Capture, Governmentality, Foucauldian Knowledge Regimes, Villaroman Inference Framework, Circumstantial Coordination Evidence, Blanket Sealing Orders, Pre-Service Sealing, Police Failure, Procedural Gatekeeping, Shareholder Record Manipulation, 9,000% Billing Markup, Cognitive Liberty, Mental Privacy, Neurotechnology, Biodigital Convergence, Surveillance, UN A/HRC/57/61, UN A/HRC/58/58, UN A/RES/58/6, Charter s.2(b) Expression, Charter s.7 Fundamental Justice, Charter s.8 Unreasonable Search, Constitutional Form vs. Substance, Accountability Foreclosure, Legitimacy Crisis, Two-Tier Justice System.

I. INTRODUCTION: THE INADEQUACY OF CONVENTIONAL EXPLANATIONS

A. The Judicial Error Hypothesis

Traditional legal scholarship analyzes adverse outcomes through frameworks of judicial error: misapplication of law, procedural irregularities, evidentiary mistakes, or bias. Appellate review exists precisely to correct such errors, operating on the assumption that mistakes are episodic, identifiable, and remediable through established mechanisms.

This framework cannot account for what occurred across British Columbia and Nova Scotia courts between 2021-2025. The pattern exhibits systematic coordination across:

-

Twenty-plus institutional actors (BCSC chambers judges, BCCA justices, NSSC judges, NSCA justices, SCC Registry, RCMP detachments, BC Securities Commission, NS Barristers' Society, Attorney General offices)

-

Four years of consistent trajectory despite changes in judicial personnel

-

Multiple binding authorities cited but not applied (Sherman Estate, Vavilov, Beals, Babos/Tobiass, Baker, Power v. Power, Hryniak, Dagenais-Mentuck, Sierra Club)

-

Escalating coercion (sealing → contempt → custody threat → extreme security barriers) despite unexamined probative evidence

-

Systematic foreclosure of every accountability avenue (criminal investigation declined, regulatory complaints dismissed, discovery prevented, appeals sealed, SCC leave denied)

When errors occur consistently, coordinately, and directionally across independent institutions—all serving to prevent examination of specific evidence while advancing enforcement of facially implausible billing—the "error" hypothesis loses explanatory power.

B. The Bad Apple Hypothesis

A second conventional explanation attributes institutional dysfunction to individual bad actors: corrupt judges, negligent police, captured regulators. This hypothesis predicts that involving different personnel would produce different outcomes, and that documentary evidence of malfeasance would trigger institutional correction mechanisms. Neither prediction holds. The documentary record shows:

-

Personnel rotation produced identical outcomes: Different BC chambers judges (Cameron → Tucker → MacNaughton → Crossin → Majawa), different NS judges (Rosinski → Smith → Norton → Keith), different NSCA justices (Beaton → Van den Eynden → Bourgeois → Bryson → Derrick)—yet the trajectory remained constant

-

Documentary evidence was systematically ignored: Shareholder records showing CSR freeze + derecognition policy; billing invoices showing 737.7 hours for 867 minutes of court time; contradictory closure documents; sworn affidavits on corporate perjury—all filed, all cited, none examined

-

Institutional safeguards failed coordinately: Internal complaints (judicial conduct, law society, police oversight) produced no investigation; external oversight bodies (Ombudsman, Human Rights Commission, Privacy Commissioner) declined jurisdiction; media contact resulted in silence or story removal

The pattern suggests not individual corruption but institutional coordination—which requires explanation beyond "bad apples."

C. The Complexity Hypothesis

A third explanation attributes systemic dysfunction to legitimate complexity: cases involving multiple jurisdictions, technical corporate matters, and self-represented litigants naturally produce sub-optimal outcomes due to resource constraints, coordination challenges, and procedural difficulties. This hypothesis fails on several grounds:

First, the legal issues were straightforward. The core questions—Did the billing bear any relationship to work performed? Did shareholder records reconcile? Should probative documentary evidence be examined before enforcement?—required no specialized expertise, only basic engagement with filed materials.

Second, the procedural violations were elementary. Courts sealed files without Sherman Estate analysis, certified costs without Bradshaw proportionality review, refused discovery without reasons, and dismissed appeals citing "no arguable issue" where binding Supreme Court authorities directly challenged lower court decisions. These are not complexity errors; they are foundational breaches.

Third, coordination across complexity should produce chaos, not convergence. When multiple independent actors and/or agencies face coordination challenges, the expected outcome is inconsistency, delay, and scattered decision-making. Instead, the pattern shows remarkable convergence: every institution declined examination, every procedural avenue closed, every enforcement mechanism activated—despite no formal coordination mechanism, no shared case management, no inter-institutional communication on record.

Complexity cannot explain synchronized institutional behavior serving a unified directional outcome.

ChatGPT 5 THINKING / Anthropic (ClaudeAI) / PerplexityAI - Full Record Audit

Gemini / Grok - Cut & Paste Review

II.- It Began in 2020

Caged by a CAGE

On September 18th, 2020, the Director of a federally-sponsored Commercial and Government Entity (“CAGE”) is alleged to have made an attempt to acquire my investment holding in the same entity through a generic Share Transfer and Power of Attorney agreement, unlinked to a specific share purchase transaction and dollar amount. This agreement was bundled alongside draft materials for a M&A share purchase acquisition. The same acquisition was linked to a shareholder agreement I was not governed by, and the Share Transfer and Power of Attorney Agreement was precluded from the digital signature record containing the remainder of materials germane to the transaction. In retrospect, this document reassigned ownership of my shares without remuneration. I was asked to sign the documents in this bundle on extremely short notice, and I did so, whereas I trusted the Director. Following sign-off, nothing happened and the CAGE entity remained silent.

Note: Shares are property rights; opaque, “for value received” transfers unmoored from an actual bargain are inherently suspect: Salomon v. Salomon & Co. [1897] A.C. 22; fair-treatment expectations under BCE Inc. v. 1976 Debentureholders, 2008 SCC 69.

Three months later, the director said the deal had been blocked by a tech partner and that the partner arrangement barred any further acquisitions until December 2022—and that there was no discretionary buy-back at any material time. For the next seven months, the director refused to disclose shareholder records, even threatening “consequences” if I contacted his records office—despite my statutory right to inspect records under s. 46 of the Business Corporations Act (S.B.C. 2002, c. 57). After another four months of silence, the BC Registrar ordered disclosure on May 3, 2021. The employee roster page disappeared from the company website the day after that order—raising obvious concerns about record preservation.

Note: Inspection and record-keeping duties: BCBCA s. 46 (shareholder inspection), s. 42 (Central Securities Register). Interference with access and post-order deletions are squarely at odds with shareholders’ reasonable expectations: BCE, 2008 SCC 69 (oppression framework).

The disclosure was compelling. The Central Securities Register (CSR) showed all shareholder activity ceased on April 14, 2020—five months before the proposed M&A date. At the time, CAGE had 70+ employee option-holders (with at least 41 past their initial vesting), and the director had repeatedly described them as “shareholders.” Historically, option exercises appeared at predictable intervals; after April 2020, nothing. The CSR listed only 19 shareholders, and no entries after April 2020. The company also omitted its FY2020 audit from the initial disclosure, even though prior years’ audits had appeared between February and April.

Note: A CSR is a definitive ownership record: BCBCA s. 42. A sudden, unexplained freeze against a background of regular exercises contradicts reasonable expectations and invites scrutiny under BCE.

The records also showed the director had created an isolated shareholder agreement for me dated July 27, 2016, while the remainder of the Common Non-Voting class appeared to be governed by a materially different agreement dated July 25, 2016, listing the other shareholders by name—and that “class” agreement was later referenced in the 2020 M&A memo. The CSR reflected a significant transfer from CAGE to a holding company on July 27, 2016.

Note: Selective/bespoke governance within a single class—without transparent disclosure—cuts against fair-treatment and reasonable-expectation principles: BCE; see also fiduciary/loyalty concepts applied to shareholder relations, Frame v. Smith, [1987] 2 S.C.R. 99 (analogous duties of loyalty and vulnerability).

On July 1, 2021 (after the company’s Annual Reference Date), I requested updated records. I was told the FY2020 audit—ordinarily out months earlier—was “awaiting signature” by a regional CPA. When produced on July 9, 2021, the audit introduced a derecognition policy that would conceal any 2020 share transfers, omitted currency data, and showed a $1.5M variance from prior, stable year-over-year values. The updated CSR (July 9, 2021) was unchanged from May 3, 2021 except that the former VP Finance—who resigned shortly after the disclosure order—now appeared in both the Common Non-Voting and Common B Non-Voting CSRs. No other activity appears on any CSR after April 14, 2020.

Note: Directors and controllers must not frustrate transparent ownership disclosure or defeat shareholder comparability; patterns that obscure material changes engage reasonable-expectation and oppression analysis: BCE. Maintaining accurate registers is a statutory obligation: BCBCA s. 42; a sustained refusal to provide records triggers relief under s. 46 and supports a remedial investigation. Where financial statements adopt a one-off treatment that undermines comparability in a way that disadvantages a holder, courts scrutinize for oppression and misrepresentation (see BCE; civil misrepresentation principles in Queen v. Cognos Inc., [1993] 1 S.C.R. 87).

Taken together—the generic transfer/POA outside the core transaction record, the months-long obstruction of inspection rights, the CSR freeze from April 2020, the bespoke 2016 agreement applied only to me, and the FY2020 derecognition with missing currency data and an unexplained $1.5M delta—the documentary trail is consistent with concealment of share movements and frustration of my statutory and equitable rights as a securityholder.

Note: Remedies include an oppression order compelling disclosure, rectification of registers, and fair-value relief: BCBCA s. 227; BCE, 2008 SCC 69.

Routine Activities Stopped in April 2020.

Empty CSR, save for VP Finance, who resigned three days following the disclosure order.

Derecognition Policy

FY 2020 Share Transfers Remain Hidden

III. - The Shareholder Oppression Matter

Whereas no discretionary buy-back was available—and after ten months of oppressive conduct and glaring anomalies in CAGE’s shareholder records—I retained a local firm in New Westminster, BC and commenced a Petition in the Supreme Court of British Columbia seeking an investigation and payment of the full value of my shareholding. The matter is characterized by willful negligence in counsel, bad faith negotiations, and had resulted in a forced settlement.

Retained Counsel - Evidence of Collusion

I retained counsel to compile, analyze, and file originating materials and to serve CAGE and its director. The firm assembled an 830-page initial affidavit saturated with sensitive shareholder and business records and filed it with the Petition on August 4, 2021. Despite confidentiality covenants in every CAGE shareholder agreement (including mine), counsel did not seek a targeted sealing/redaction order at filing. Competent counsel should have asked the court for minimally impairing protection with reasons addressing necessity, proportionality, and alternatives (the open-court/sealing framework in Vancouver Sun (Re), 2004 SCC 43; Sierra Club of Canada v. Canada (Minister of Finance), 2002 SCC 41; Sherman Estate v. Donovan, 2021 SCC 25). Their failure fell below the standard of a reasonably competent solicitor (concurrent contractual/tort duty per Central Trust Co. v. Rafuse, [1986] 2 S.C.R. 147).

After filing and service, CAGE’s counsel first advised there was “no rush to seal", then presented a steeply discounted settlement offer. The director told me this reflected the correct share value. I replied that I was willing to settle after a due-diligence review of the derecognized audit entries and I cited s. 2(a) of the Charter and my core values against expedient compromise where systemic wrongdoing might be at issue. The director agreed to take steps toward an investigation.

The file was sealed by consent on August 27, 2021 via redactions. Two weeks later, on September 13, 2021, CAGE served a default notice alleging that my failure to obtain sealing on August 4 breached the shareholder agreement and that the prior settlement offer was off the table; I was told my shares would be “automatically bought back” at $3.60 per share. This pivot from “no rush” to default, weaponizing a sealing lapse the other side had downplayed, is difficult to reconcile with the duty of honest performance and good-faith exercise of contractual discretion (Bhasin v. Hrynew, 2014 SCC 71; C.M. Callow Inc. v. Zollinger, 2020 SCC 45; Wastech Services Ltd. v. GVRD, 2021 SCC 7).

At that point, my own counsel said they would not assist further—even though their initial lapse created the pretext for default. Worse, they filed over-broad redactions that went beyond what the judge had authorized and removed my pleaded request for an investigation, leaving a record that made the lawsuit read as unnecessary or vexatious (echoing CAGE’s incorrect claim that I had a discretionary buy-back). They then refused to file corrected redactions; I filed them myself. In my view, those acts compounded the prejudice and further departed from the standard of competent, candid representation (Central Trust).

I asked the director to withdraw the default notice in light of his prior commitment to diligence—and because the file had already been sealed. He repeated the original offer without investigation and demanded signature within two weeks. Given those developments, I retained a second firm in Surrey to conduct diligence on the director’s settlement affidavit and assume carriage of the file.

After I signed the retainer and provided a deposit, the second firm went silent for a week. I sent four follow-ups requesting the promised diligence; all were ignored. On the eve of the director’s deadline, the firm wrote that they could not send a formal recommendation. In the same breath, they admitted that a valuation expert was required to vet share value but urged me to sign immediately anyway. Advising execution while acknowledging that essential diligence was outstanding failed the duty to provide competent, timely, and responsive advice within the retainer’s scope (Central Trust).

Exhausted and facing an engineered deadline with no practical alternative, I signed the settlement CAGE drafted. The circumstances reflect a convergence of inequality of bargaining power and improvidence—hallmarks of unconscionability (Uber Technologies Inc. v. Heller, 2020 SCC 16; Harry v. Kreutziger (1978), BCCA; Morrison v. Coast Finance (1965), BCCA). They also resonate with undue influence/economic duress principles where wrongful or illegitimate pressure, coupled with blocked diligence, drives consent (Geffen v. Goodman Estate, [1991] 2 S.C.R. 353; Greater Fredericton Airport Authority v. NAV Canada, 2008 NBCA 27). A settlement procured amid material non-disclosure or misrepresentation is susceptible to rescission (Rick v. Brandsema, 2009 SCC 10 (family context, disclosure principle); Zheng v. Yuandian Investment Group Ltd., 2017 BCSC 1813, para 52).

Post-execution, further irregularities appeared: an uncashable settlement cheque, mismatched file numbers between my retainer and operative files, and a statement of services that omitted the settlement’s conclusion and payout. After I pressed for a complete record, the firm issued a revised account “writing off” the closure work. While a $987 discount is by no means a misfortune, the omissions and after-the-fact write-off are outliers that support an inference of opportunistic performance and record-keeping inconsistent with the duty of honesty in performance (Callow; see also Wastech).

Causally, but for competent advice and a minimally impairing sealing/redaction application at filing—the obvious course under Vancouver Sun/Sierra Club/Sherman Estate—there would have been no contractual pretext for default and no manufactured time pressure; correspondingly, but for the second firm’s failure to execute the diligence retainer, I would not have faced a sign-now-or-default ultimatum. That is classic but-for causation on a balance of probabilities (Clements v. Clements, 2012 SCC 32; Athey v. Leonati, [1996] 3 S.C.R. 458).

My Retained Legal Counsel Filed Confidential Shareholder Records at the Public Registry Without My Knowledge, Instruction, nor Consent. The CAGE and I Agreed on a Sealing Order Remedy. The CAGE Then Issued a Default Notice Following Seal Entry. My Counsel Claimed Bad Faith, and Withdrew.

The Same Counsel Scrubbed Incriminating Details in the Public Record

IV. - CAGE Settlement Affidavit

Following events in September and October 2021 concerning the foregoing, it became evident that there were a series of false statements in the CAGE director’s sworn Settlement Affidavit.

1) False statements about who counts as a “shareholder.”

The affidavit asserts that employee stock option holders only become shareholders when their employment ends. That is contradicted by the Central Securities Register (CSR) showing a complete cessation of activity after April 14, 2020, despite multiple departures thereafter. At the time the CAGE affidavit was sworn, ten former employees who would ordinarily be expected to appear as shareholders were absent from the CSR—an implausible pattern which assumes that groups of rational actors simply chose to abandon valuable rights. After the CAGE removed its employee roster from its website the day after the May 3, 2021 disclosure order, I corroborated the former-employee population using LinkedIn, archive.org captures of the team page, and other third-party sources, and then validated those against the CSR. The sworn affidavit thus occasions a prima facie account of perjury.

Note: When affidavit assertions conflict with contemporaneous documentary records, courts give the documents primacy: Bradshaw v. Stenner, 2010 BCCA 398, paras 186–191; see also the single civil standard of proof in F.H. v. McDougall, 2008 SCC 53. CSR accuracy and access flow from BCBCA ss. 42 & 46; electronic/business records are admissible if properly authenticated: Canada Evidence Act s. 30 (business records), ss. 31.1–31.3 (electronic records).

2) Contradictory accounts of the same “partner termination” event.

The affidavit gives two different dates for the termination of CAGE’s partnership with a separate tech company—the very event the 2020 share-purchase cancellation supposedly turned on. A six-month delta between those versions implies a six-month revenue variance with potential tax consequences. I preserved the underlying materials and mapped them to the CSR and audit timelines. It is noted that the false date the CAGE director provided on December 4th, 2020 had coincided with the 2-year BC statute of limitations act.

Note: Such discrepancies justify seeking third-party records and, where appropriate, regulatory attention. CRA evidence can be reachable in civil proceedings subject to the Income Tax Act confidentiality framework—see ITA s. 241(3)(b), (3.1)—and courts have recognized routes to obtain relevant tax information and testimony in appropriate cases: Slattery (Trustee of) v. Slattery, [1993] 3 S.C.R. 430 (see Part V). Hawitt v. Campbell (1983), 46 B.C.L.R. 260 (C.A.) outlines the test for misrepresentation, fraud, and/or collusion in a settlement. Credibility conflicts of this sort typically require a trial process rather than a paper disposition: Hryniak v. Mauldin, 2014 SCC 7; Inspiration Management Ltd. v. McDermid St. Lawrence Ltd. (1989), 36 B.C.L.R. (2d) 202.

Two Accounts of Perjury in the CAGE Director's Settlement Affidavit

Paragraph 10, Settlement Affidavit

"While options for Common Non-Voting Shares continue to vest, the decision to exercise options is a decision of each individual optionee. Individual optinonees are not required to exercise options as they vest."

Ie., they collectively threw away money.

Missing from Central Securities Register

-

8 Verified Tier-1 Former Employees

-

13 Verified Tier-2 Former Employees

Common Non-Voting CSR is empty beyond April 2020 with one exception; the former VP Finance, who resigned shortly after the May 3rd, 2021 disclosure order. The Common B Non-Voting CSR is empty with the exception of the same individual.

Employee Roster webpage

deleted on May 3, 2021

V. - Onset of Disruptive Zersetzung: November 2021 through February 2022

Beginning in late November 2021, my day-to-day life unraveled. I experienced on-heels stalking, vehicle break-ins, home intrusions, repeated computer hijackings, unauthorized bank activity, and threats of abduction, torture, and death—both via hijacked PC events and in person from strangers. During several remote-access incidents, I was shown images of the CAGE director alongside a set of recurring actors; the same personas then populated YouTube channels pushed to me regardless of whether I was logged in, and real-world events were telegraphed online before they happened. On one occasion, a remote session displayed video of the interior of my Surrey condo.

Note: Criminal Code anchors: s. 264 (criminal harassment), s. 264.1 (uttering threats), s. 342.1 (unauthorized use of computer), s. 430(1.1) (mischief to data), s. 348 (breaking & entering), s. 346 (extortion, where threats coerce conduct), s. 423 (intimidation).

There were public attempts to implicate me, including an effort to obtain my fingerprints at a New Westminster church (mid-December 2021). I could not walk my building or a city block without being stalked and photographed; the online cohort pre-announced these encounters. At the same time in Nova Scotia, my mother began receiving calls impersonating my nephew, using family-specific language to solicit banking details.

Note: Criminal Code: s. 403 (identity fraud/personation). Privacy tort (persuasive authority): Jones v. Tsige, 2012 ONCA 32 (intrusion upon seclusion).

In parallel, work evaporated. Ordinary engagements derailed between meetings without any precipitating act on my part; beginning November 2021, every income source (and pending opportunity) collapsed, and I have been unemployed since. Efforts to obtain new counsel—including programs for which I qualified—were met with a priori rejections before subject matter was discussed, and unexplained but consistent midstream reversals. I swore to these facts in an Affidavit on May 20, 2022.

Note: Intentional interference with economic relations by unlawful means: A.I. Enterprises Ltd. v. Bram Enterprises Ltd., 2014 SCC 12 (elements: intention, unlawful means, resulting loss).

I sought help at the Surrey RCMP. An officer wearing a mental-health badge spoke with me outside, heard the account, but declined to open a file or investigate. He appeared to know of the situation preemptively, as is reflected in the May 20, 2022 Affidavit. Later FOIPOP records (via Halifax Regional Police) confirm my attendances. It became clear I would receive no customary relief, and I was living alone under daily intimidation.

Note: Tort of negligent investigation recognized: Hill v. Hamilton-Wentworth Police Services Board, 2007 SCC 41 (standard is reasonableness, not perfection).

On February 8, 2022, after multiple break-ins and a major remote takeover where a caricature of the CAGE director uttered threats of death and identity theft on my laptop, I filed S-220956 at the Vancouver Registry with a draft petition and my January 24, 2022 Affidavit (settlement test and perjury proof). I did not intend to open a file while unrepresented and unemployed, but in the absence of police recourse—and given my plan to proceed under normal conditions later—placing evidence before a formal institution was understood as a necessary cautionary act.

I Fled for my Life

On February 16, 2022, after further break-ins, hijacks, and a specific threat that I would be abducted that night (maintenance had covered my windows and adjacent units with tarps), I relocated. I loaded what I could— including a hardcopy of my S-220956 affidavit—into my car and drove across Canada in mid-winter. I could hear laughter in the adjacent room, and persons describing the triggering PC intrusion event with specific references. I was followed and photographed multiple times while loading my vehicle. It was clearly a state-adjacent operation. After three tow rescues in blizzards, I reached Halifax, Nova Scotia, and arranged an early lease termination.

Two days after arriving, a local computer-shop owner preemptively called me a “political target” and, in the same conversation, suggested it would be pointless to remove a “specialty program” from my laptop. Online harassment resumed in Nova Scotia and on-heels activity restarted within two weeks. Early that March, a man claiming to be CAF approached and threatened me; on speakerphone, a second person also claiming CAF recited private details about the British Columbia incidents. I detail these events in my May 20, 2022 Affidavit.

Note: Possible offences: s. 403 (personation/identity fraud), s. 419 (unauthorized use of military uniforms/insignia, where applicable), s. 264.1 (threats).

That same affidavit—the first notarized account of these incidents beyond RCMP records—was couriered from Halifax to Vancouver the day it was commissioned. While it was en route, CAGE’s counsel threatened to strike S-220956 without explanation. No one other than the notary knew of the affidavit’s existence (see Exhibit A to my Aug. 23, 2023 Affidavit). At that time, S-220956 was three months old with an outstanding order for audit discovery. I held back filing the May 20 affidavit linking the director to the events that precipitated the petition. CAGE did not act on the strike threat. When I added the materials in July 2022, CAGE then demanded a seal of the entire file—including public exhibits—which the court granted. In chambers, treatment of these events was muted.

Note: Sealing must satisfy Sherman Estate v. Donovan, 2021 SCC 25 (necessity, proportionality, alternatives). Blanket, file-wide seals—especially over public exhibits—are exceptional and require reasons.

For conceptual clarity, I have referred to the pattern as “Zersetzung” (a term commonly used to describe systematic, psychologically disintegrative harassment). The scope, regularity, and sophistication—digital hijacks, synchronized in-person stalking, impersonation calls using private family idiom, employment and counsel interference, and file-wide sealing—are reasonably expected to preclude an assumption that the CAGE had marshalled these resources to act independently. The consistency and breadth of the pattern make it difficult to assess an isolated actor hypothesis, as does the manner of RCMP posture.

Note: Where unknown persons orchestrate online/offline campaigns, civil tools include Norwich orders to identify wrongdoers: Rogers Communications Inc. v. Voltage Pictures, LLC, 2018 SCC 38; BMG Canada Inc. v. Doe, 2005 FCA 193; and interlocutory injunctions under the RJR-MacDonald test, [1994] 1 S.C.R. 311. Criminal peace-bond relief: s. 810.

Note: Zersetzung (pronounced [t͡sɛɐ̯ˈzɛt͡sʊŋ], German for "decomposition" and "disruption") was a psychological warfare technique used by the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) to repress political opponents in East Germany during the 1970s and 1980s. Zersetzung served to combat alleged and actual dissidents through covert means, using secret methods of abusive control and psychological manipulation to prevent anti-government activities. People were commonly targeted on a pre-emptive and preventative basis, to limit or stop politically incorrect activities that they may have gone on to perform, and not on the basis of crimes they had actually committed. Zersetzung methods were designed to break down, undermine, and paralyze people behind "a facade of social normality" in a form of "silent repression".

PsyOp | Cyber | Mischief | Zersetzung Began Shortly Following the Shareholder Settlement [Link]

"Trust Account"

____________

The RCMP Did Not Respond

They Were Aware

Per the adjacent Affidavit excerpt and a report pulled by local police cited below it, I made multiple attempts to solicit RCMP support in response to the events that began following the 2021 CAGE shareholder dispute. The RCMP appeared to have a priori knowledge of these incidents, and could have taken a few easy steps to address the ongoing and serious crimes involved. Namely, they could have obtained CCTV video footage from the condo building I was living in at the time. These would have demonstrated the ongoing break-ins which were occurring. Likewise, they could have assigned their cyber team. I have not been able to secure any help for almost three years, despite diligent solicitation. The RCMP was not asked to play the role of a judge, notwithstanding the fact that their negligence had occasioned the filing of S-220956, and an emergency relocation across Canada in mid-winter. Having said that, the RCMP must investigate crimes related to civil proceedings, being the same perpetrators, and likewise, investigate the conduct of public registry employees pursuant to CCC 139. Finally, it must recognize a clear matter of criminal interference.

I was Consistently Denied Fiduciary Legal Support, Including ProBono, from November 2021 Onward

VI. - S-220956: Feb 2022 through Nov 2022

In February 2022 at the onset of S-220956, irrespective of the conditions initiating the same, I had a basic expectation of a fair and impartial judicial system. The entirety of this proceeding is chronicled at the Civil page (here). Mindful of negligence by my retained counsel in August 2021 in failing to apply for a seal of the shareholder oppression affidavit at its onset, I had asked the court to temporarily seal the file on submitting the pleadings with a hand-written application on February 8th, 2022, which it agreed to on consent of the parties.

Milestone 1 — Discovery pathway opened (Apr 1, 2022).

My first substantive request was to furnish the evidentiary record with the derecognized and privileged audit data, alongside the shareholder records contradicting the director’s settlement affidavit. I relied on Hawitt v. Campbell (1983), 46 B.C.L.R. 260 (C.A.); re-opening settlements where there is a triable issue of fraud/collusion/limitation/misapprehension; and Justice Iacobucci’s discussion in Slattery (Trustee) v. Slattery, [1993] 3 S.C.R. 430 (Part V) that tax records may be necessary to reach the correct disposition.

On April 1, 2022, Master Cameron agreed and ordered service on CRA with my application for audit disclosure (citing ITA s. 241(3) and related provisions), and further directed that, failing agreement between the Parties, that directions be sought on how (not if) to serve three private, material entities: (i) the CAGE's CPA firm, (ii) the holding company identified in the Sept 2020 share-purchase memo, and (iii) the technology partner said to have triggered cancellation. Opposing counsel vigorously objected, but did not appeal. Shortly after, I was told the adjudicator retired.

Note: Discovery’s truth-seeking role: Spar Aerospace, 2002 SCC 78; “don’t short-circuit discovery where facts are contested”: Boxer Capital, 2005 ONCA; summary process must remain proportionate to justice, not a shortcut around evidence: Hryniak v. Mauldin, 2014 SCC 7.

Milestone 2 — The pathway is smothered (May–Aug 2022).

What should have been a straightforward execution of the April 1 2022 order was then suppressed through a sequence of short chambers appearances. Two hearings immediately after April 1 were held in private rooms, contrary to BCSC Civil Rules 22-1(5) and the open-court principle (Vancouver Sun; Sherman Estate). On June 27, 2022, over my objection and with no evidentiary foundation of necessity, a chambers judge granted a blanket protection order over an already-sealed file, justified on speculation that I might disclose sealed materials before directions on mode of service—despite a April 27, 2022 letter confirming directions would be sought on service method, pursuant to the order. The judge stated the order was “reasonably required” so the seal could “properly function,” refused to address mode of service on the three third parties, and then required me to seek permission to execute the April 1 2022 undertaking. That became the template for later protection extensions.

Note: Sealing/protection requires necessity, proportionality, and rejection of workable alternatives with reasons; blanket/file-wide orders are exceptional: Sherman Estate; Dagenais/Mentuck. Converting a subsisting discovery order into a leave-to-act regime without reasons invites re-litigation/relitigation abuse concerns: Toronto (City) v. C.U.P.E., 2003 SCC 63.

Milestone 3 — CRA disclosure squeezed into short chambers; referral judge signs pre-drafts (Aug 2022).

CRA counsel opposed the April 1 disclosure route and, together with opposing counsel, faxed the court to shoehorn my CRA motion into a 30-minute short-chambers list in August 2022 alongside a CAGE motion for a proximate summary hearing. I wrote the court explaining the application was not ready (mode-of-service directions were still outstanding) and that a short-chambers slot was disproportionate to the issues’ importance. Despite registry staff lacking authority to dictate an applicant’s dates, the request was granted. A referral judge—who admitted unfamiliarity with the file—cut off my ITA 241/222 submissions and dismissed the CRA route, then signed pre-drafted orders authorizing the petition to proceed by summary judgment, effectively relitigating the April 1 2022 discovery structure.

Note: Process must be proportionate and reasons must grapple with the live constraints: Hryniak; Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, paras 86, 105, 126–128. When material credibility/document conflicts exist, summary determination is inappropriate: Inspiration Management, 36 B.C.L.R. (2d) 202 (C.A.).

Milestone 4 — Stay refused; April 1 order ignored (Sept 2022).

I appealed the short-chambers/summary turn and sought a stay so the April 1 order could be executed first. The appeal chambers judge dismissed the stay and ended the hearing abruptly when I turned to ITA 241(3) and 222 and the Iacobucci rationale for audit disclosure, including ITA 241(3.1) concerning the related criminal activity (see Guide).

Note: Stays are assessed under RJR-MacDonald, [1994] 1 S.C.R. 311; where a prior, subsisting discovery order is being functionally nullified without reasons, there is at least a serious issue to be tried. The duty to give responsive reasons remains: Vavilov.

Milestone 5 — Summary hearing granted in my absence; petition dismissed.

I notified opposing counsel that, per April 1, the petition could not be properly tried without lawful audit data (ITA s. 241(3)(b)) and that key action items remained outstanding. Opposing counsel moved to proceed in my absence. I filed a response: appearing at a summary hearing would validate re-litigating a subsisting order in the same court (R. v. Babos, 2014 SCC 16, [2014] 1 S.C.R. 309 at paragraphs 76-78). In a five-minute appearance, the court ignored the April 1 requirements and granted a summary hearing before opposing counsel alone. The petition was later dismissed as a “fishing expedition,” even though the same judge had recently endorsed robust investigation in A Lawyer v. Law Society of British Columbia, 2021 BCCA 437 (arising from routine audit triggers). The transcript shows the shareholder record conflicts were not engaged, nor the procedural foreclosures, nor the related criminal element.

Bottom line.

A reasoned discovery pathway opened on April 1, 2022 was then choked off by protection/sealing expansions, private-room hearings contrary to Rule 22-1(5), short-chambers compression, pre-drafted orders, and a summary determination that never grappled with the CSR/audit contradictions or the CRA+CPA disclosure route. On any fair application of Sherman Estate, Hryniak, Vavilov, Wolkins, Tayo Tompouba, Spar Aerospace, and C.U.P.E., that sequence does not meet the standard of transparent, proportionate, intelligible adjudication. Severe optics (R v. Wolkins).

S-220956: Former Deputy AG & Minister of Justice Frank Iacobucci Authored the Audit Test

Charitable Donations

An actionable vector toward resolving the scandal resides in a CRA tax audit. As shown earlier in the page, the CAGE Settlement Affidavit contains two accounts of perjury, one of which triggers an immediate consideration of section 222 of the Income Tax Act. Forensic audit is likewise expected to address the criminal interference components. The legal test is below.

Audit Discovery

Former Deputy Attorney General and Deputy Minister of Justice Frank Iacobucci set forth the legal test for the authorization of testimony by CRA officials in civil proceedings, using the legislation in section 241(3) of the Income Tax Act as a basis. Section 241(3.1), which provisions testimony without a legal test, is viable by means of the criminal element involved. Per the account in the Litigation page, the BCSC and BCCA suppressed the initial order by a now-retired adjudicator made April 1st, 2022 to introduce testimony by CRA officials. This was obstructed in a manner that ignored relevant legal tests in addition to the framework presented by the former Deputy Attorney General as shown.

ITA Section 241(3), (3.1)

The jurisprudence in Slattery (Trustee of) v. Slattery, [1993] 3 S.C.R. 430 outlines a legal test which refutes the notion that testimony by CRA officials in civil proceedings is limited to matters brought under the Income Tax Act itself. The test is exceptionally broad insofar as a matter need only have some measure of relationship to the enforcement of the Income Tax Act. Per the Litigation page testimony and in the redacted Affidavits, this test was pushed aside in a series of proceedings in 2022 in favor of pre-drafted orders provided by counsel.

Settlement Affidavit

Absent consideration of ITA 241(3.1) as it relates to the criminal mischief surrounding the proceeding, the Settlement Affidavit sworn by the CAGE Director on September 22nd, 2021 contains two accounts of perjury. One involves shareholder materials and CAGE shareholders, and the other involves two conflicting tax accounts concerning a partner entity that the BCSC initially asked to be joined. To that end, the legal test in Slattery is met with respect to the civil matter relating to the enforcement of the Act. That same insight occasioned the initial BCSC order on April 1st, 2022.

“To comply with section 7 of the Charter, the magistrate must make a decision based on the facts and the law. In the extradition context, the principles of fundamental justice have been held to require, “at a minimum, a meaningful judicial assessment of the case on the basis of the evidence and the law. A judge considers the respective rights of the litigants or parties and makes findings of fact on the basis of evidence and applies the law to those findings. Both facts and law must be considered for a true adjudication. Since Bonham’s Case [(1610), 8 Co. Rep. 113b, 77 E.R. 646], the essence of a judicial hearing has been the treatment of facts revealed by the evidence in consideration of the substantive rights of the parties as set down by law” (Ferras, at para. 25). The individual and societal interests at stake in the certificate of inadmissibility context suggest similar requirements.”

Charkaoui v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), [2007] 1 S.C.R. 350, 2007 SCC 9 at paragraph 48

"Thus, in my view, the powers granted to the Law Society by s. 36(b) of the LPA, and as operationalized by R. 4-55 of the Law Society Rules, should be read broadly to permit the investigation of a member’s entire practice, as that may in certain circumstances be the best means to uncover the truth and protect the public and to determine whether disciplinary action should be taken."

BCSC Chambers Judge Andrew Majawa in A Lawyer v The Law Society of British Columbia, 2021 BCSC 914 at paragraph 63

“Justice is not only about results, it is about how those results are obtained”.

R. v. Babos, 2014 SCC 16, [2014] 1 S.C.R. 309 at paragraph 85

The BCSC Agreed With Privileged Discovery. The Proceedings Went Awry Following the Order.

CAGE Counsel sought special costs in their response to S-220956 in March 2022, claiming the matter was frivolous. The BC Supreme Court disagreed on April 1st, 2022, acknowledging that allegations of fraud, perjury, and collusion were evident at face value. Service was ordered on CRA and private entities related to the 2021 dispute. The file was later compromised.

At a Hearing Unlawfully Held in Private [Rule 22-1(5)], a BCSC Judge Encumbered the Discovery Order.

CRA Vigorously Opposed Discovery, Despite a Tax Enforcement Issue in the File [ITA, Section 222]. CRA Counsel Did Not Address the Iacobucci Legal Test. Citizens Understand the CRA to be an Objective Public Agency. BCSC Registry Staff Booked an Early Hearing Date Without the Consent of the Applicant.

There is No Analogue for the CRA Response, nor the Aggressive Pushback and Insistence on Urgency.

Res Judicata: CAGE Pre-Drafted Order Templates Seeking a Proximate Summary Hearing Were Signed

Following the April 1st, 2022 order, a series of chambers appearances were held in private rooms in violation of BSCS Rule 22-1(5). The proceedings were then guided by dishonest and false narratives which the court accepted at face value, ignored legal tests, abuse of process, and the approval of pre-drafted orders which held contempt for the discovery order, and sought to relitigate the matter of audit testimony (Res Judicata). These actions sought to re-write the overarching narrative.

The BC Appellate Court Blocked an Appeal of the Draft Orders Prior to the Summary Hearing

The matter of ongoing criminal interference was precluded from treatment in the file despite the same being obvious. The BCCA replicated the same manner of obstruction. The adjacent transcript depicts an instance where a BCCA judge closed chambers when the issue of CRA testimony was raised in accord with the April 1st, 2022 order, and ITA 241(3.1) concerning criminal offenses.

Abuse of Process, and Indeed, the Prejudicial Disposition of Authority, is a Heinous Violation of Charter Rights in the

Section 7 Level of Analysis. An Incomplete but Relevant List of Applicable Caselaw is Cited in the Authorities Page [Here].

Related & Ongoing PsyOp-Style Harassment | Pop-Ups, Algorithms, & CIMIC Mischief [see Guide]

CAGE Director

Scandal in the S-220956 Dismissal by BCSC Justice Andrew Majawa

Majawa Decision. S-220956 dismissed as a "fishing expedition", despite proof of fraud, perjury, and an outstanding order for audit data. The Decision text is Suffused with glaring falsehoods like this.

As compared to the decision text, there was no service of materials. An order to seek direction on service modality to related entities had already been made on April 1st, 2022, and the Parties had Agreed on the Roadmap (below). The manner of scandal evidenced is not limited to Majawa J.

S-220956 Majawa Decision: "The Evidence Does Not Matter."

Legal counsel was retained to establish a precedent for the Affidavit, review it multiple times, critique it, commission it, file it, and serve it on the CAGE Director. Counsel was aware of confidential information beginning at page 674 of the Affidavit, but did not file an Application for a sealing order. I am not legally trained, and whereas, counsel was retained to act independently on my behalf. Trained lawyers are not expected to make such mistakes in gross negligence. Justice Majawa was aware of these details.

Per Affidavit records, my governing Shareholder Agreement is dated July 27th, 2016. A different governing Agreement for other CAGE shareholders is dated July 25th, 2016. Notwithstanding, an unbiased judge would not claim that a loss of a quarter-million dollars, as a result of an act of gross negligence by retained counsel, following the execution a remedy the Parties agreed on, is germane to the object and proportion of justice.

Per Groberman J., Coast Foundation v. Currie, 2003 BCSC 1781 at paragraphs 13, 15;

“The question of when the court ought to give judgment on an issue, as opposed to on the claim generally, is more complex. The court is justifiably reluctant to decide cases in a piecemeal fashion. In addition to all of the concerns that arise when the entire claim is before the court, there is a multitude of others. The result is that the court must exercise considerable caution before coming to the conclusion that it should grant judgment on an issue in a summary trial [...] The court must also be wary of making determinations on particular issues on a Rule 18A application when those issues are inexorably intertwined with other issues that are to be left for determination at trial: Prevost v. Vetter, 2002 BCCA 202, 210 D.L.R. (4th) 649; inter-relatedness of issues is not always obvious, and caution is necessary whenever a party seeks judgment on an issue as opposed to Judgment generally under Rule 18A: B.M.P. Global et al v. Bank of Nova Scotia, 2003 BCCA 534, [2003] B.C.J. No. 2383”

This is the only mention in the Majawa decision that makes any reference to the Zersetzung components related to the file. Likewise, no consideration was made regarding the conditions that occasioned the opening of S-220956 to begin with. Numerous legal tests apply concerning matters substantially related to the proceedings, and the encumbrances imposed on litigants in the absence of fiduciary support;

-

Pintea v. Johns, 2017 SCC 23, [2017] 1 S.C.R. 470 at paragraph 4;

-

Girao v. Cunningham, 2020 ONCA 260 at paragraphs 156, 174, 177;

-

Jonsson v Lymer, 2020 ABCA 167 at paragraphs 14, 60, 71, 85, 86.

Macfarlane J.A. promulgated the standard settlement test in Hawitt v. Campbell, [1983] CanLII 307 at paragraph 19;

The judge may refuse the stay if:

1. There was a limitation on the instructions of the solicitor known to the opposite party;

2. There was a misapprehension by the solicitor making the settlement of the instructions of the client or of the facts of a type that would result in injustice or make it unreasonable or unfair to enforce the settlement;

3. There was fraud or collusion;

4. There was an issue to be tried as to whether there was such a limitation, misapprehension, fraud or collusion in relation to the settlement.

The CSR (Central Securities Register) demonstrates that the CAGE Director committed an act of perjury in his Settlement Affidavit. The same Affidavit likewise contains two conflicting tax accounts concerning a company the CAGE entity was formerly partnered with. The remainder of evidence forms a broad compendium including shareholder agreements, communications, audit reports, behaviors, and more (Redacted November 22nd, 2023 Affidavit, pages 98 through 153, as linked here). This is why a (now-retired) BCSC adjudicator ordered service on CRA and related private entities on April 1st, 2022, according to the legal test in Hawitt.

The derecognition of assets clause in the CAGE entity's FY2020 Fiscal Report as shown on page 121 of the Redacted Affidavit reads as follows:

"The Company derecognizes financial assets only when the contractual rights to cash flows from the financial assets expire, or when it transfers the financial assets and substantially all of the associated risks and rewards of ownership to another entity. Gains and losses on derecognition are generally recognized in the consolidated statements of operations."

This would conceal any share transfers in the relevant year (see page 108). The consolidated statements themselves likewise yield relevant deltas (page 122).

This statement by a Federally-Appointed judge concerning the size of a Petition Record binder as a vetting mechanism is as reckless as it is antagonistic to the object and proportion of justice. Likewise, this judge ignored an outstanding mandate set previously in the same court concerning the introduction of audit data by CRA and three private entities related to the shareholder dispute. Section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and Section 2(e) of the Bill of Rights require fair proceedings, which require a court to adjudicate matters on all relevant facts and law, and to ensure a fair process;

-

Ruffo v. Conseil de la magistrature, [1995] 4 S.C.R. 267 at paragraph 38;

-

New Brunswick (Minister of Health and Community Services) v. G. (J.), [1999] 3 S.C.R. 46 at paragraphs 73 through 75 and 119;

-

Charkaoui v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), [2007] 1 S.C.R. 350, 2007 SCC 9 at paragraphs 29, 41, 48;

-

United States of America v. Cobb, [2001] 1 S.C.R. 587, 2001 SCC 19 at paragraph 53.

Charkaoui v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), [2007] 1 S.C.R. 350, 2007 SCC 9 at paragraph 29;

“This basic principle has a number of facets. It comprises the right to a hearing. It requires that the hearing be before an independent and impartial magistrate. It demands a decision by the magistrate on the facts and the law. [...] Precisely how these requirements are met will vary with the context. But for section 7 (of the Charter) to be satisfied, each of them must be met in substance.”

Shareholder records account for a fraction of filed materials. Specifically, they furnish 18.3% of the November 22nd, 2023 compendium Affidavit, and smaller proportions in other documents. Some Affidavits contained none, but were nonetheless sealed. A blanket sealing order over these materials is a violation of settled Constitutional law. Likewise, settlement privilege does not apply when the settlement itself is an issue. An overarching concern in a permanent complete seal is preclusion of this scandal from the public, whereas the same censorship precludes intervention because people are not properly informed about the file. Most importantly, the sealing orders concealed the conditions that occasioned the opening of S-220956, the obstruction of justice within the file, and the external criminal activities related to and impacting it. The sealing orders were made to conceal the scandal.

-

Sherman Estate v. Donovan, 2021 SCC 25 at paragraph 1, 35, 75, 79, 85, 87, 91, 94,

-

United States v. Meng, 2021 BCSC 1253 at paragraph 33

-

Nguyen v. Dang, BCSC 1409 at paragraph 23

I filed a basket of evidence concerning two accounts of perjury in the CAGE Director's Settlement Affidavit, a basket of shareholder evidence (pages 98-153 in the November 22nd, 2023 Redacted Affidavit), and an order made on April 1st, 2022 in the same court to adduce privileged audit data accordance to the legal test in Hawitt v. Campbell, [1983] CanLII 307 at paragraph 19, as predicated on the merit in the file. More importantly, I gave an account of the conditions that occasioned the inception of the file, and whereas the same events breach section 3.2 of the Settlement Agreement as shown on the Zersetzung page. Yet, this miscarriage of justice resulted in a half-million dollars in special costs awarded to the perpetrators. How, and why?

Justice Majawa Had Set an Opposite Precedent in His Other Rulings

The foregoing closing comments in the S-220956 Majawa decision are diametrically opposed to the precedents he has set in other matters concerning access to justice. S-220956 was no fishing expedition; it was supported with hard evidence including two separate accounts of perjury in the CAGE Director's Settlement Affidavit. This was likewise recognized through an order to obtain privileged audit testimony. With respect to the initial shareholder dispute, the CAGE Director issued a default notice made possible through an act of gross negligence by my retained legal counsel, following the execution of the remedy for the same breach. Whereas this act by counsel is palpable gross negligence, and by means of the behavior of retained counsel following this act, collusion cannot be ruled out. The same likewise would align with the remainder of evidentiary components in this scandal. Notwithstanding that I had no intention to open S-220956 as an unrepresented and unemployed litigant beset by ongoing criminal mischief substantially related to the same Respondents, the file exactly met the criteria set forth in Hawitt. The thesis of third-party interference set forth in this website is supported through a comparison of other precedents set by the same judge. One such example I would cite here is A Lawyer v. The Law Society of British Columbia, 2021 BCSC 914.

In Lawyer, justice Majawa ordered a sweeping investigation of an entire law practice on the basis of a hypothesis by the LSBC. Anneke Driessen, a LSBC staff lawyer, wrote on February 11th, 2022;

"The auditor identified, among other things, that you may have allowed clients to use your trust accounts for the flow of funds in the absence of substantial legal services related to those funds and/or in the absence of making reasonable inquiries," wrote Anneke Driessen, a law society staff lawyer on Feb. 11, 2020.”

The foregoing hypothesis is compared with hard evidence presented in my first Affidavit of S-220956, which BSCS Master Cameron acknowledged on April 1st, 2022 as compelling enough to serve on Canada Revenue Agency, a CPA firm, a former partner company of the CAGE entity, and the holding company contemplated in the 2020 M&A action. Lawyer much more closely resembles a "fishing expedition" by comparison.

In Lawyer at paragraph 63, justice Majawa positioned the principle of fundamental justice as being vectored toward "uncovering the truth" and "protecting the public". He called for a broad rather than narrow disposition of investigative powers, similar to the jurisprudence of Iacobucci J. in Slattery (Trustee of) v. Slattery, [1993] 3 S.C.R. 430 as it relates to the testimony of CRA officials in civil matters (pages 161-162 in the Redacted November 22nd, 2023 Affidavit). With respect to relevant analysis, one must highlight a theme of using the "best means" to enable an outcome consistent with relevant key principles. The BCSC has a different mandate than the LSBC. The question being, did the BCSC use the best means available at its disposal to adjudicate in accordance with fundamental justice, germane to BCSC Rule 1-3? Or, were the powers of the bench used in a capacity opposite to its mandate? S-220956 began on solid footing, but the proceedings were severely and consistently derailed in a way that can only be described as unnatural, and subject to criminal interference which was never addressed in any capacity.

In S-220956, Justice Majawa obstructed justice by ignoring a previous order made in the same court, ignoring hard evidence, ignoring customary jurisprudence and legal tests, ignoring his own jurisprudence, insulating wrongdoers from prosecution, violating Constitutional Law, and awarding special costs to the CAGE Director against every legal test concerning it. Justice Majawa suppressed the truth, and endangered the public, allowing palpable wrongdoing to remain unaddressed, and in fact, rewarding it. As detailed in the Zersetzung page, matters germane to this scandal will and do inexorably victimize other people. Justice Majawa presided over a weaponized bench in S-220956.

At the request of counsel for the Attorney General of Canada, as is detailed in the forthcoming sections, justice Majawa, a BCSC chambers judge, and in violation of nine (9) rules of procedure concerning the BCSC and the Class Proceedings Act, dismissed S-229680 similar to S-220956. He likewise imposed severe and unfounded encumbrances affecting access to justice concerning the matters of this scandal. His actions made it nigh impossible to uncover the truth and protect the public, absent the actions of whistleblowers.

Finally, the jurisprudence in Lawyer is applicable to an investigation of the CAGE Director's trust accounts, as is contemplated further on.

For reasons unbeknownst to me, the court proceedings were not only choreographed; they were politicized. A normal court stamp appears on the left. To its right, the stamp for my motion to justice Majawa contains a feather. Not a smudge; a feather.

Test Criteria: Institutional & Judicial Impartiality

R. v. Lippé, [1991] 2 S.C.R. 114 sets forth a legal test concerning bias, impartiality, and integrity is understood to be a matter of perception by reasonable, fair-minded, and informed persons, which has not been set aside.

R. v. Lippé, [1991] 2 S.C.R. 114 on institutional impartiality;

“If a judicial system loses the respect of the public, it has lost its efficacy."

VII. - S-228567 & S-229680:

Oct 2022 through April 2023

By September 2022, it was clear that I was facing a systemic and structural problem. Contemporaneous to an appeal of S-220956, I commenced a new class proceeding addressing the CAGE, the Government of Canada, and a coordinated cohort of harassment actors (I pleaded them collectively as “Defendant4” to reflect an aggregated wrongdoer group, cf. representational/aggregation dynamics discussed in Salna v. Voltage Pictures, LLC, 2021 FCA 176). The claim sought a basket of remedies for Charter (ss. 2(a), 2(b), 7), privacy, and human-rights violations, systemic justice obstruction/negligence, and for the costs initially awarded to the director in S-220956.

S-228567 → S-229680 (Class Proceedings track).

I filed S-228567 in October 2022 as a bridge to what became S-229680. Throughout 2022, I could not secure counsel—even government-sponsored pro bono programs for which I met criteria—and private firms disengaged a priori, before subject matter was discussed (find the complete account of this here). Both opposing counsel correctly noted that the relief I sought in S-228567 could not proceed by petition, so I discontinued and re-filed as S-229680 under the Class Proceedings Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 50 (CPA)—the proper vehicle for the scope and issues I pleaded.

Sealing spread to files that contained only public material.

My affidavit in S-228567 contained no sworn narrative—only public social-media and web content already in the public domain. Yet the same judge who allowed S-220956 to go forward as a summary matter (ignoring the April 1, 2022 discovery order) sealed S-228567—including that public-domain exhibit set. The Application Record for that hearing even misidentified CAGE’s counsel as counsel for the Government of Canada. The Government’s official counsel did not attend and “took no position,” despite the open-court and freedom-of-expression interests directly engaged by a sealing order (Vancouver Sun (Re), 2004 SCC 43; Canadian Broadcasting Corp. v. New Brunswick (AG), [1996] 3 S.C.R. 480; Sherman Estate v. Donovan, 2021 SCC 25 (necessity, proportionality, and workable alternatives). The effect was censorship of public materials via court order.

S-229680 was sealed before service—and later scrubbed from the e-registry.

On December 13th, 2022, S-229680, the properly-filed replacement of S-228567, was sealed prior to the CAGE accepting service of the pleadings, and prior to a court hearing. This discovery was made that day while logged into BC Court Services Online, and whereas, CAGE counsel had emailed acceptance of service within thirty seconds of me making that discovery online (one of the many contributing evidentiary components concerning surveillance). Counsel for AG Canada was silent. My supporting affidavit in S-229680 likewise relied on overlapping public materials. In January 2023, I discovered that my originating pleadings had likewise been removed from the electronic court registry entirely.

Note: Open-court principle applies to civil filings absent justified, tailored restrictions; scrubbing core pleadings from public access demands reasons addressing Sherman Estate’s test; publication bans/seals cannot be a default, Dagenais/Mentuck.

Case management was acknowledged—then quietly sidestepped.

Also in January 2023, the BCSC acknowledged my request for a case-management judge and case-planning conference in S-229680, as contemplated by Practice Direction 5 (class proceedings management), which interfaces with the CPA and related Rules. Three days later, counsel for the Attorney General of Canada wrote that S-229680 would instead be sent to the same chambers judge who had handled S-220956 in the manner I say obstructed justice. Over the next ten weeks, no fewer than nine serious, categorical procedural departures followed; the court ignored my written requests to correct course and declined to discuss by phone. In April, the Chief Justice replied that an order made outside the proper procedural parameters was nonetheless “in effect,” without engaging the detailed account of obstruction I provided (cf. Criminal Code s. 139). The practical result was to block a trial of common issues from proceeding in the BCSC.

Note: Courts must provide transparent, intelligible, and justified reasons that grapple with the governing legal constraints: Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, paras 86, 105, 126–128. Class matters are ordinarily case-managed to safeguard fairness and proportionality; departures from the structure contemplated by PD-5/CPA should be explained. Where sealing/publication limits are sought, courts must consider alternatives and tailoring, not adopt blanket secrecy, per Sherman Estate; see also duty to facilitate access to justice and not erect process barriers: Trial Lawyers Assn. of BC v. BC (AG), 2014 SCC 59.

Bottom line.

Across S-228567 and S-229680, the court extended sealing/protection from S-220956 to public-domain materials, pre-service pleadings, and even e-registry visibility, while ignoring rules that governed the style of proceeding. Those moves run head-on into the open-court and proportionality jurisprudence (Vancouver Sun; CBC v. New Brunswick; Sherman Estate; Dagenais/Mentuck) and the reason-giving and fair-process requirements (Vavilov). The cumulative effect was to foreclose a principled adjudication of the common issues in a forum designed by statute to hear them.

An Overt and Palpable Violation of Procedure Requested by the Attorney General of Canada

Charter Matter S-229680 Was Sealed Extrajudicially at Inception

Pleadings Scrubbed From Registry Database

Declared a Vexatious Litigant for Filing Charter Matter S-229680

The Merit in the File

The excerpts above this section touch on the compelling issues brought before the BCSC. A prima facie account of shareholder fraud exists by means of the materials presented, as well as compelling evidence of collusion with the legal counsel I had retained to manage the 2021 dispute. The CAGE settlement affidavit likewise contains two accounts of perjury. The intent of the CAGE CEO is visible in records dating back to September 2020 both within and beyond courtrooms. This was first acknowledged by the BCSC on April 1st, 2022 per the adjacent, and later by local police prior a false report being filed. The existence of bias and collusion in the proceedings is evidenced through the disposition of litigation in response to the evidentiary record and its applicable legal tests. When the wrong judgments are issued, it evidences corruption. When they are issued repeatedly, it indicates scandal.

PD-27 Corrective Letters

The BCSC ignored five (5) letters sent over ten (10) weeks under Practice Direction 27, in response to the serious Rule violations cited earlier in the page. Each letter was less than five (5) pages. In the adjacent excerpt, Majawa J. treats reasonable corrective efforts as vexatious in character.

An Assertion of Prolix & Convoluted Filings

S-220956 and S-229680 are distinctly different files. The latter is a Charter matter that sought different relief, which counsel from both the CAGE and AG Canada advised could not be brought by Petition, as was the case with S-220956. As a result, S-228567 was discontinued and replaced by S-229680. In scandalous fashion, the latter file was sealed extrajudicially, and dismissed amid rule violations, at the request of AG Canada.

Majawa's assertion of convoluted filings is disingenuous, and is inconsistent compared with the observation of other adjudicators, as is exampled in the adjacent transcript excerpt. Further evidence of the same may be gleaned through CAGE Affidavits filed in an out-of-province court. By means of the excerpt below, it required just thirty-six (36) minutes for CAGE counsel to review a 143-page Affidavit I filed, thus suggesting an ease of review. It likewise underscores the felonious character of the cost scandal which had originated in British Columbia through a CAGE Affidavit in filed in BC. Finally, my academic background should be noted. It is difficult for an accredited institution to sign a postgraduate certificate if the student habitually produces indiscernible trash. Reasonable persons can glean, through the excerpts on this page, that the court had acted in a prejudicial capacity.

Self-Represented Litigants

From November 2021 onward, I was without fiduciary legal counsel despite best efforts to obtain the same. As shown earlier in this page, my retained counsel in the 2021 CAGE dispute had jeopardized the file through disclosing materials without my knowledge nor consent. The SCC held that self-represented litigants are afforded additional protections. In consideration of the same, a series of applicable legal tests are detailed below, and also in the Authorities Page.

Vexatious Declaration as a Procedural Foreclosure Mechanism

Unfounded Tools to Affect Foreclosure

Concerning the consideration that must be afforded to self-represented litigants (and notwithstanding the fact that I was forced to represent myself at all times), the Supreme Court of Canada held in Pintea v. Johns, 2017 SCC 23, [2017] 1 S.C.R. 470 at paragraph 4;

“We would add that we endorse the Statement of Principles on Self-represented Litigants and Accused Persons (2006) (online) established by the Canadian Judicial Council.”

Girao v. Cunningham, 2020 ONCA 260 (“Girao”), Lauwers J.A underscores the foregoing precedent set in Pintea concerning the Statement of Principles on Self-represented Litigants and Accused Persons, at paragraphs 156 , 176, and 177;

“The impression left by the limited trial record is that the trial judge allowed himself to be led by trial counsel’s arguments. Ms. Girao, a self-represented, legally unsophisticated plaintiff who struggled with the English language, was left to her own devices. Fairness required more, consistent with the expectations placed on the trial judge by Statement of Principles on Self-represented Litigants and Accused Persons.” [...] “Ms. Girao was entitled to but did not get the active assistance of the trial judge whose responsibility it was to ensure the fairness of the proceeding. As a self-represented litigant, she was also entitled to, but did not get, basic fairness from trial defense counsel as officers of the court. The trial judge was also entitled to seek and to be provided with the assistance of counsel as officers of the court, in the ways discussed above. This did not happen." [...] I would allow the appellant’s appeal, set aside the judgment and orders, and order a new trial. I would award the costs of this appeal and of the trial to the appellant, including her disbursements.”

Concerning vexatious declarations specifically, Slatter J. wrote in Jonsson v Lymer, 2020 ABCA 167 at paragraph 14;

“Vexatious litigants must be distinguished from self-represented litigants. Merely because a self-represented litigant uses a process that is not in accordance with the Rules of Court, or advances a claim without merit does not mean that they are vexatious. Many self-represented litigants are unfamiliar with court procedures, and are inadequately or inaccurately informed about their legal rights and the limitations on them. Merely because the self-represented litigant excessively or passionately believes in the merit of his or her cause does not make them vexatious.”

At paragraphs 85 and 86 in Lymer, the court concludes that self-represented litigants should not be denied access to justice through onerous orders limiting their participation, in an absence of more reasonable and customary provisions;

“Parties are entitled to self-represent, and the court should be sensitive to the challenges faced by self-represented litigants. Vexatious litigant orders should only be made when other procedural techniques have proven to be inadequate and the offensive conduct is persistent. [...] In conclusion, the appeal is allowed. The vexatious litigant order should not have been granted in these circumstances, and in any event the form of order granted was overbroad. The sanction for contempt cannot stand given the failure to afford the appellant a fair hearing. The question of sanction for contempt is referred back to the trial court for a fresh hearing before a different judge."

Duties owed to a self-represented litigant (SRL).

I was forced to be self-represented throughout. The Supreme Court in Pintea v. Johns, 2017 SCC 23 (para 4) endorsed the CJC’s Statement of Principles on SRLs, requiring judges and counsel to actively facilitate a fair process. The Ontario Court of Appeal in Girao v. Cunningham, 2020 ONCA 260 (paras 156, 176–177) reinforces that duty: SRLs are entitled to active judicial assistance and basic fairness from opposing counsel as officers of the court. Where that support is absent, the remedy can be a new trial with costs to the SRL. My experience was the opposite—procedural traps, silence to corrective requests, and orders issued without reasons that engaged the live constraints.

Vexatious-litigant rhetoric is not a substitute for case management.

On “vexatiousness,” Jonsson v. Lymer, 2020 ABCA 167 draws a bright line: an SRL’s missteps or weak claims do not make them vexatious, albeit, the BC files were extremely substantial, as this website should indicate. Lymer also stresses proper case management as the proportionate response to complexity and friction (para 60): courts should craft tailored management orders or a litigation plan rather than impose boilerplate restrictions. And at paras 85–86, the court holds SRLs must not be denied access to justice through overbroad participation limits; draconian orders require proof that lesser techniques failed. What had happened is in direct opposition to these guardrails. In my proceeding, case management mandated by BCSC Practice Direction 5 (acknowledged by BCSC Scheduling on Jan. 27, 2023) was then displaced after the Attorney General’s counsel asserted—extra-procedurally and via email—that the file would return to the same chambers judge who had dismissed S-220956. Over the next ten weeks, nine categorical procedural departures followed; staff did not engage with my written corrections and declined phone discussion. When I raised this with the Chief Justice in April, I was told an order made outside proper parameters nevertheless “stood,” without addressing the obstruction concerns I identified (Criminal Code s. 139). The effect was to block a trial of common issues under the Class Proceedings Act, which likewise blocks any provincial (Criminal) actions. The result was a foreclosure of justice avenues.

Applying the standards to what happened.

-

Bias (Lippé / Wewaykum / Yukon Francophone): repeated routing to the same judge despite PD-5, sealing/publication controls expanding without tailored necessity, and pre-service, file-wide protection orders together create the perspective of an objective, informed observer that the playing field was tilted.

-

Reasonableness (Vavilov para 104): reasons repeatedly did not grapple with the governing legal constraints (PD-5, open court, proportionality), and justified outcomes through circular premises (“seals are necessary so the seal can function”).

-

SRL fairness (Pintea / Girao): I did not receive active assistance; opposing counsel did not supply the cooperative candour expected of officers of the court; and the remedy track chosen amplified rather than reduced asymmetry.

-

Proportional case control (Lymer): instead of a tailored management order and litigation plan, I faced overbroad restrictions and scheduling maneuvers that foreclosed a merits hearing.

Bottom line.

Even if one charitably chalks up isolated missteps to “honest mistakes,” the concurrence of events—inside and outside the courtroom—meets the definition of a scandal: a sequence that an informed person, viewing matters practically, would read as compromising impartiality and reasonableness, contrary to Lippé, Vavilov, Pintea, Girao, and Lymer. Per the case law in R. v. Tayo Tompouba, 2024 SCC 16 at paragraph 73;

"Courts have found a miscarriage of justice in a wide range of circumstances (see A. Stylios, J. Casgrain and M.‑É. O’Brien, Procédure pénale (2023), at paras. 18‑87 to 18‑81). Examples of a miscarriage of justice include the ineffective assistance of counsel (see White), a breach of solicitor‑client privilege by defence counsel (Kahsai, at para. 69, citing R. v. Olusoga, 2019 ONCA 565, 377 C.C.C. (3d) 143) and a misapprehension of the evidence that, though not making the verdict unreasonable, nonetheless constitutes a denial of justice (R. v. Lohrer, 2004 SCC 80, [2004] 3 S.C.R. 732, at para. 1; Coughlan, at pp. 576‑77). Unfairness resulting from the exercise of a “highly discretionary” power, related to proceedings leading to a conviction and attributable to a judge will also generally be analyzed under the miscarriage of justice framework (Fanjoy, at pp. 238‑39; Kahsai, at paras. 72 and 74)."

VIII. - Meeting with Halifax Regional Police (“HRP”), December 8th, 2022