Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act (S.C. 2000, c. 24) [Link]

Reasonable Grounds Defined

Measuring Police Response Against Case Law

February 7th, 2025

LEGAL STANDARDS FOR POLICE INVESTIGATION DUTIES

REASONABLE GROUNDS, REASONABLE SUSPICION, AND THE DUTY TO INVESTIGATE

Constitutional Foundation

Constitution Act, 1982, Preamble and Section 7:

"Whereas Canada is founded upon principles that recognize the supremacy of God and the rule of law: [...] Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice."

Significance: Constitutional rights to liberty and security impose corresponding duties on state actors—including police—to act reasonably, diligently, and in accordance with fundamental justice when investigating crimes and responding to complaints.

I. THE POLICE DUTY TO INVESTIGATE

A. The Overarching Standard: Reasonableness in the Circumstances

Hill v. Hamilton-Wentworth Regional Police Services Board, [2007] 3 S.C.R. 129, 2007 SCC 41, para 58 (McLachlin C.J.):

"All the tort of negligent investigation requires is that the police act reasonably in the circumstances. It is reasonable for a police officer to investigate in the absence of overwhelming evidence—indeed evidence usually becomes overwhelming only by the process of investigation. Police officers can investigate on whatever basis and in whatever circumstances they choose, provided they act reasonably. [...] They may arrest or demand a breath sample if they have reasonable and probable grounds. And where such grounds are absent, they may have recourse to statutorily authorized roadside tests and screening."

Principle: The duty to investigate is governed by an overarching standard of reasonableness, not a single fixed evidentiary threshold. The reasonableness of investigating—or declining to investigate—depends on what information the police possess and what investigative powers that information authorizes.

B. The Non-Abdicable Duty

R. v. Beaudry, [2007] 1 S.C.R. 190, 2007 SCC 5, para 35:

"There is no question that police officers have a duty to enforce the law and investigate crimes. The principle that the police have a duty to enforce the criminal law is well established at common law."

Hill v. Hamilton-Wentworth, para 44:

"The effective and responsible investigation of crime is one of the basic duties of the state, which cannot be abdicated. [...] The enforcement of the criminal law is one of the most important aspects of the maintenance of law and order in a free society. Police officers are the main actors who have been entrusted to fulfill this important function."

Principle: The police duty to investigate is:

-

Non-abdicable: Cannot be refused or delegated away

-

Fundamental: Central to rule of law and public safety

-

Public interest: Affects not just individuals but societal confidence in justice system

C. The Public Interest in Preventing Negligent Investigations

Hill, para 36 (McLachlin C.J.):

"The personal interest of the suspect in the conduct of the investigation is enhanced by a public interest. Recognizing an action for negligent police investigation may assist in responding to failures of the justice system, such as wrongful convictions or institutional racism. The unfortunate reality is that negligent policing has now been recognized as a significant contributing factor to wrongful convictions in Canada. While the vast majority of police officers perform their duties carefully and reasonably, the record shows that wrongful convictions traceable to faulty police investigations occur. Even one wrongful conviction is too many, and Canada has had more than one. Police conduct that is not malicious, not deliberate, but merely fails to comply with standards of reasonableness can be a significant cause of wrongful convictions."

Referenced Inquiries:

-

The Honourable Peter Cory, The Inquiry Regarding Thomas Sophonow (2001)

-

The Right Honourable Antonio Lamer, The Lamer Commission of Inquiry (2006)

-

Federal/Provincial/Territorial Heads of Prosecutions Committee, Report on the Prevention of Miscarriages of Justice (2004)

-

The Honourable Fred Kaufman, The Commission on Proceedings Involving Guy Paul Morin (1998)

Principle: Police negligence—even without malice or deliberate misconduct—can cause wrongful convictions and systemic failures. Courts recognize actionable duty to prevent such harms through reasonably competent investigations.

II. THE INVESTIGATIVE THRESHOLD: REASONABLE SUSPICION

A. Definition: The Lowest Investigative Standard

R. v. Mann, 2004 SCC 52, [2004] 3 S.C.R. 59, para 34:

"Police officers may detain an individual for investigative purposes if there are reasonable grounds to suspect in all the circumstances that the individual is connected to a particular crime and that such a detention is necessary."

R. v. Chehil, 2013 SCC 49, [2013] 3 S.C.R. 220, para 27:

"Reasonable suspicion is a lower standard than reasonable and probable grounds. [...] It must be based on objectively discernible facts, which can then be subjected to independent judicial scrutiny."

Chehil, para 26:

"In every context, the reasonable suspicion standard ensures courts can conduct meaningful judicial review of what the police knew at the time [...] This standard requires the police to disclose the basis for their belief and to show that they had legitimate reasons related to criminality for targeting an individual."

At paragraphs 32, 35, and 40;

"Thus, while reasonable grounds to suspect and reasonable and probable grounds to believe are similar in that they both must be grounded in objective facts, reasonable suspicion is a lower standard, as it engages the reasonable possibility, rather than probability, of crime. As a result, when applying the reasonable suspicion standard, reviewing judges must be cautious not to conflate it with the more demanding reasonable and probable grounds standard. [...] Finally, the objective facts must be indicative of the possibility of criminal behaviour. While I agree with the appellant’s submission that police must point to particularized conduct or particularized evidence of criminal activity in order to ground reasonable suspicion, I do not accept that the evidence must itself consist of unlawful behaviour, or must necessarily be evidence of a specific known criminal act. [...] The application of the reasonable suspicion standard cannot be mechanical and formulaic. It must be sensitive to the particular circumstances of each case."

What Reasonable Suspicion Requires:

-

Objective facts: Not hunches, intuition, or bare speculation

-

Connection to specific crime: Facts must suggest particular criminal activity

-

Articulable basis: Police must be able to explain the factual foundation

-

Independent scrutiny: Courts assess facts objectively, not deferring to police conclusions

What Reasonable Suspicion Does NOT Require:

-

Proof of probability (suspicion suffices)

-

Complete investigation

-

Elimination of innocent explanations

-

Legal training or expertise to articulate

B. Investigative Powers Available at Reasonable Suspicion

When police have reasonable suspicion, they possess lawful authority to:

-

Investigative detention (Mann): Briefly detain person to investigate

-

Protective searches (Mann): Pat-down search for officer safety

-

Screening devices (Hill): Roadside screening tests, drug-sniffing dogs (Chehil)

-

Questioning: Ask questions, request identification, seek explanations

-

Non-intrusive investigation: Review records, interview witnesses, examine documents

Critical Inference: If reasonable suspicion authorizes intrusive investigative powers (detention, search), then it necessarily triggers a duty to investigate using less intrusive means.

C. Application to Duty to Investigate

The Logical Framework: Police cannot reasonably say, "We had sufficient facts to justify detaining and searching this person, but we chose to do nothing at all."

Where information meets reasonable suspicion:

-

Police possess investigative authority under Mann and Chehil

-

Police must exercise that authority reasonably under Hill

-

Flat declination to investigate becomes difficult to defend: if facts justify intrusion, they justify investigation

The reverse application of R. v. Ahmad, 2020 SCC 11, para 24:

"This standard requires the police to disclose the basis for their belief and to show that they had legitimate reasons related to criminality for targeting an individual."

If police must show "legitimate reasons related to criminality" when they act (detain, search), they must show "legitimate reasons unrelated to criminality" when they decline to act (refuse to investigate), where reasonable suspicion exists (e.g., they have already investigated and charged another suspect conclusively, or, the jurisdiction lies elsewhere and it is not impacting the victim in their policing jurisdiction).

Principle for Complaints: Where a complainant provides objective facts suggesting a person is connected to criminal activity—meeting the Mann/Chehil standard—police cannot decline to investigate without articulating a legitimate, justifiable reason unrelated to the facts themselves.

III. THE COERCIVE THRESHOLD: REASONABLE GROUNDS TO BELIEVE

A. Definition and Unified Terminology

Baron v. Canada, 1993 CanLII 154 (SCC), [1993] 1 S.C.R. 416, at 447:

"As Wilson J. said in R. v. Debot, the standard to be met in order to establish reasonable grounds for a search is 'reasonable probability.' It appears that the normal statutory phrase in Canada is 'reasonable grounds,' and that some of the remaining exceptions requiring 'reasonable and probable grounds' may have been amended in recent years, one imagines for the sake of uniformity, by deleting the words 'and probable'."

Terminology: "Reasonable grounds" and "reasonable and probable grounds" are synonymous—both require "reasonable probability" standard.

B. Reasonable Grounds Distinguished from Reasonable Suspicion

R. v. Phung, 2013 ABCA 63, para 10 (Paperny J.A.):

"As for what 'reasonable grounds' itself means, the standard was first described in Hunter v. Southam, [1984] 2 S.C.R. 145, at 114-115 as 'the point where credibly-based probability replaces suspicion.' It has since been characterized in terms of 'reasonable probability': R. v. Debot, [1989] 2 S.C.R. 1140 at 1166. This is a standard higher than a reasonable suspicion but less than a prima facie case."

The Hierarchy of Standards:

Mere suspicion: Unsubstantiated belief—insufficient for any action.

Reasonable suspicion: Suspicion based on objectively discernible facts—sufficient for investigative detention, protective searches, screening devices, and (as discussed above) sufficient to trigger duty to investigate.

Reasonable grounds to believe: Credibly-based probability—sufficient for arrest, search warrants, breath demands, and (as discussed below) creates a near-absolute duty to investigate.

Prima facie case: Evidence sufficient to establish case absent rebuttal—required for proceeding to trial.

Balance of probabilities: More likely than not (>50% probability)—civil litigation standard.

Beyond reasonable doubt: Proof to moral certainty—criminal conviction standard.

C. The Mugesera Framework for Reasonable Grounds

Mugesera v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), [2005] 2 S.C.R. 100, 2005 SCC 40, para 114:

"The 'reasonable grounds to believe' standard requires something more than mere suspicion, but less than the standard applicable in civil matters of proof on the balance of probabilities. In essence, reasonable grounds will exist where there is an objective basis for the belief which is based on compelling and credible information."

Tripartite Test:

-

Objective basis: Not subjective belief or hunch

-

Compelling information: Substantial, not trivial or speculative

-

Credible information: Reliable, trustworthy sources or evidence

Gordillo v. Canada (Attorney General), 2022 FCA 23, para 112:

"The 'reason to believe' standard [...] requires something more than mere suspicion, but less than the standard applicable in civil matters of proof on the balance of probabilities and [...] reasonable grounds will exist where there is an objective basis for the belief which is based on compelling and credible information."

Principle: Reasonable grounds exist when objective, compelling, and credible information creates reasonable probability—not certainty, not even likelihood on balance of probabilities, but reasonable probability warranting investigation.

D. Investigative Powers and Duties at Reasonable Grounds

When police have reasonable grounds to believe a crime has been or is being committed, they possess authority to:

-

Arrest without warrant (Criminal Code s. 495)

-

Obtain search warrants (Criminal Code s. 487)

-

Demand breath samples (impaired driving)

-

Lay criminal charges

-

Seize evidence

-

Execute all investigative powers available at lower thresholds

Critical Application to Investigation Duty: At reasonable grounds, the duty to investigate becomes virtually non-abdicable:

-

Facts establish credibly-based probability of crime

-

Police possess full coercive authority to investigate

-

Declination conflicts with fundamental duty recognized in Beaudry and Hill

-

Public interest demands investigation (preventing wrongful convictions, maintaining confidence)

The Core Principle: Where information meets reasonable grounds to believe, police cannot reasonably decline to investigate absent extraordinary circumstances (jurisdictional issues, ongoing related investigation, safety concerns requiring alternate approach). The duty is triggered, and the question becomes not "whether to investigate" but "how to investigate competently."

IV. THE UNIFIED FRAMEWORK: WHEN INVESTIGATION IS REQUIRED

A. The Spectrum of Duty

The duty to investigate operates along a spectrum corresponding to the level of information available:

Below Reasonable Suspicion: Police may investigate using minimal powers (observation, consensual interviews). No duty to investigate where information is purely speculative, but police retain discretion to investigate if acting reasonably.

At Reasonable Suspicion (Mann/Chehil threshold): Police possess investigative powers (detention, questioning, screening). Declination difficult to defend: if facts justify intrusion, they justify investigation. Police must provide legitimate reason for declining investigation where reasonable suspicion exists.

At Reasonable Grounds to Believe (Mugesera threshold): Police possess coercive powers (arrest, search, charges). Declination objectively indefensible absent extraordinary circumstances. Duty is non-abdicable at this level—investigation required to fulfill fundamental state function.

B. The Operative Principle for Complainants

Summary Standard: At a minimum, where information supplied by a complainant meets the reasonable suspicion standard recognized in Mann and Chehil—and certainly where it meets reasonable grounds to believe—the police cannot reasonably decline to investigate.

A refusal in those circumstances conflicts with their non-abdicable duty to investigate crime recognized in Hill and Beaudry, because:

-

The information justifies investigative steps under existing law

-

The police possess lawful authority to investigate

-

No legitimate reason exists to decline exercising that authority

-

The overarching duty requires acting reasonably in the circumstances

C. Legitimate vs. Illegitimate Reasons for Declination

Legitimate Reasons (even where thresholds met):

-

Resource constraints: Crime triaged against more serious matters requiring immediate attention

-

Ongoing investigation: Investigation already underway; additional action would interfere

-

Jurisdictional issues: Another agency better positioned (different province, federal vs. provincial)

-

Safety concerns: Investigation would escalate danger to complainant or others; alternate approach required

-

Prosecutorial advice: Crown counsel advises insufficient prospect of conviction after reviewing evidence

-

Evidentiary barriers: Critical evidence legally unavailable (privilege, exclusionary rules)

Illegitimate Reasons (violate duty even if articulated):

-

Institutional solidarity: Protecting colleague, friend, or organization from scrutiny

-

Convenience: "Too much work" or "easier to dismiss than investigate"

-

Animus: "We don't like the complainant" or "complainant is difficult"

-

Prejudgment: "We don't believe it happened" without investigating

-

Improper delegation: "Let the complainant investigate and bring us proof"

-

Circular reasoning: "No reasonable grounds because we haven't investigated, won't investigate without reasonable grounds"

V. ESTABLISHING REASONABLE GROUNDS: OBJECTIVE BASIS AND CUMULATIVE EFFECT

A. The Reasonable Observer Test

Sittampalam v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2005 FC 1211, para 11 (Hughes J.):

"The existence of reasonable grounds must be established objectively, that is, that a reasonable person placed in the same circumstances would have believed that reasonable grounds existed, in the case of an arrest, to make the arrest: R. v. Storrey, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 241, at page 250."

Standard: Reasonable public scrutiny—would a reasonable, informed person in the same circumstances believe grounds existed?

Not Required:

-

Legal training or expertise

-

Certainty that crime occurred

-

Complete investigation showing overwhelming evidence

Required:

-

Objective assessment (not subjective belief)

-

Rationality (logical connection between facts and conclusion)

-

Information about circumstances (context matters)

B. Cumulative Effect and Coherence of Facts

R. v. Harding, 2010 ABCA 180, para 10 (Slatter J.A.):

"The trial judge held that Sgt. Topham had experience in enforcing drug laws, the vehicle had British Columbia plates (a province notorious for drug production), two large bags were seen in the back of the vehicle, the officer smelled a strong odour of raw marijuana, and the vehicle was a rental car (commonly used in the drug trade to avoid identification and detection). The cumulative effect of all these circumstances was sufficient to provide the objective basis for the arrest which then ensued."

Principle of Coherence:

-

Individual facts may be innocent when viewed in isolation

-

When multiple facts cohere—creating pattern suggesting criminal activity—cumulative effect establishes reasonable grounds

-

Epistemology of coherence: Multiple consistent indicators, each supporting the others, create objective basis even where no single fact would suffice alone

Application to Complaints: When citizen complaint contains multiple corroborating facts—documents, timing correlations, witness statements, physical evidence—police must consider cumulative effect, not dismiss each fact individually as insufficient.

Example from Harding:

-

BC plates alone: Common, innocent

-

Large bags alone: Common, innocent

-

Marijuana smell: Requires investigation

-

Rental car alone: Common, innocent

-

Cumulative effect: Reasonable grounds to believe drug transportation

Analogous Application to Institutional Misconduct:

-

Single procedural irregularity: Could be error

-

Timing correlation: Could be coincidence

-

Documentary contradiction: Could be mistake

-

Pattern of declinations: Could be resource constraints

-

Cumulative effect: Reasonable grounds to investigate coordination or misconduct

C. The Appearance Test for Serious Misconduct

R. v. Kahsai, 2023 SCC 20, para 67, citing R. v. Wolkins, 2005 NSCA 2, para 89:

"Scandals are predominantly ascertained by way of appearance, as deduced by reasonable and objective persons having insight into their context. The test does not require that the observers have any legal training; only that the observers be objective, rational, and informed of the circumstances."

Application to Police Conduct: Where citizen complaint alleges serious police misconduct (fabricated reports, investigation declination without legitimate reason, coordination with subjects of investigation), reasonable grounds exist if:

-

Reasonable, objective observers

-

Informed of circumstances

-

Would conclude misconduct likely occurred

This does not require complainant to prove misconduct occurred—only that circumstances create reasonable appearance justifying investigation.

VI. INFERENCE FROM CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE

A. The Bedford Standard: Reasonable Inference on Balance of Probabilities

Canada (Attorney General) v. Bedford, 2013 SCC 72, para 76 (McLachlin C.J.):

"A sufficient causal connection standard is satisfied by a reasonable inference, drawn on a balance of probabilities: Canada (Prime Minister) v. Khadr, 2010 SCC 3, [2010] 1 S.C.R. 44, at para. 21."

Civil Standard: In civil matters (including actions against police for negligent investigation), reasonable inferences drawn on balance of probabilities are sufficient to establish facts.

B. Sherman Estate: Inference vs. Speculation

Sherman Estate v. Donovan, 2021 SCC 25, paras 97-98:

"This Court has held that it is possible to identify objectively discernible harm on the basis of logical inferences. But this process of inferential reasoning is not a license to engage in impermissible speculation. An inference must still be grounded in objective circumstantial facts that reasonably allow the finding to be made inferentially. Where the inference cannot reasonably be drawn from the circumstances, it amounts to speculation. Where the feared harm is particularly serious, the probability that this harm will materialize need not be shown to be likely, but must still be more than negligible, fanciful or speculative."

Inference Standard:

-

Permissible: Logical inference grounded in objective circumstantial facts

-

Impermissible: Speculation not reasonably supported by circumstances

Threshold:

-

Need not show harm/crime is likely (>50% probability)

-

Must show harm/crime is more than negligible, fanciful, or speculative

-

Where harm particularly serious, even lower probability sufficient if reasonable basis exists

C. Lower Standard for Police Initiating Investigation

Gordillo v. Canada (Attorney General), 2022 FCA 23, para 112:

The "reasonable grounds" standard for police initiating investigation is "something more than mere suspicion, but less than the standard applicable in civil matters of proof on the balance of probabilities."

Implication: When citizen presents evidence to police:

-

Police need reasonable grounds to investigate (lower than balance of probabilities)

-

Citizen need not prove case (balance of probabilities standard)

-

Police must investigate where objective, compelling, credible information creates reasonable probability

-

Standard deliberately low to ensure crimes investigated before evidence lost or witnesses intimidated

VII. INVESTIGATION REQUIRED, NOT CONVICTION-READY CASE

A. The Fundamental Principle

R. v. Loewen, 2010 ABCA 255, para 32:

"To establish objectively reasonable grounds, the Crown needed only to show that it was objectively reasonable to believe that an offence was being committed, not that it was probable or certain."

R. v. Tim, 2022 SCC 12, para 24:

"The police are not required to have a prima facie case for conviction before making an arrest."

Principle: Police must investigate based on reasonable grounds—not proof beyond reasonable doubt, not even prima facie case, but reasonable probability warranting investigation.

B. Evidence Develops Through Investigation

Hill v. Hamilton-Wentworth, para 58 (McLachlin C.J.):

"It is reasonable for a police officer to investigate in the absence of overwhelming evidence—indeed evidence usually becomes overwhelming only by the process of investigation. [...] The lack of evidence of a chilling effect despite numerous studies is sufficient to dispose of the suggestion that recognition of a tort duty would motivate prudent officers not to proceed with investigations 'except in cases where the evidence is overwhelming.'"

Key Insights:

-

Evidence develops through investigation: Police cannot refuse investigation because evidence not yet "overwhelming"—investigation is the process by which evidence becomes overwhelming

-

Reasonableness, not certainty: Standard is reasonableness in circumstances, not certainty of guilt

-

Low threshold by design: System designed to enable investigation based on reasonable grounds, recognizing that investigation will develop fuller picture

C. Limited Pre-Investigation Requirements

495793 Ontario Ltd. (Central Auto Parts) v. Barclay, 2016 ONCA 656, para 51 (Juriansz J.A.):

"The function of police is to investigate incidents which might be criminal, make a conscientious and informed decision as to whether charges should be laid and present the full facts to the prosecutor. Although this requires, to some extent, the weighing of evidence in the course of investigation, police are not required to evaluate the evidence to a legal standard or make legal judgments. That is the task of prosecutors, defense lawyers and judges."

Barclay, para 52:

"Nor is a police officer required to exhaust all possible routes of investigation or inquiry, interview all potential witnesses prior to arrest, or to obtain the suspect's version of events or otherwise establish there is no valid defense before being able to form reasonable and probable grounds."

Principle: Police need not conduct exhaustive investigation before initiating formal investigation or arrest—reasonable grounds sufficient to begin investigation, which will then develop more complete picture.

Application to Complaints: When citizen files complaint with documentary evidence, police cannot refuse investigation on grounds that:

-

Not all witnesses interviewed yet (investigation will interview witnesses)

-

Subject's explanation not yet obtained (investigation will obtain it)

-

Some facts remain unclear (investigation will clarify)

-

Legal issues are complex (prosecutors and courts will resolve legal issues)

Police must investigate where reasonable grounds exist—investigation develops fuller picture.

VIII. JUDICIAL REVIEW STANDARDS

A. Careful Scrutiny Where Constitutional Rights at Stake

R. v. Araujo, 2000 SCC 65, [2000] 2 S.C.R. 992, para 29:

"The authorizing judge must look with attention at the affidavit material, with an awareness that constitutional rights are at stake and carefully consider whether the police have met the standard."

Principle: Where constitutional rights affected (liberty, security, privacy), courts apply heightened scrutiny to police conduct—not deferential review but careful examination of whether standards met.

B. Meaningful Judicial Review Through Objective Standards

R. v. Ahmad, 2020 SCC 11, para 24 (Karakatsanis J.):

"In every context, the reasonable suspicion standard ensures courts can conduct meaningful judicial review of what the police knew at the time [...] This standard requires the police to disclose the basis for their belief and to show that they had legitimate reasons related to criminality for targeting an individual.

An objective standard like reasonable suspicion allows for exacting curial scrutiny of police conduct for conformance to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and society's sense of decency, justice, and fair play because it requires objectively discernible facts. As is the case with warrantless searches, 'the trial judge [must be] . . . in a position to ascertain [these objective facts], and not bound by the personal conclusions of the officer who conducted the [investigation]' [...] This is essential to upholding the rule of law and preventing the state from arbitrarily infringing individuals' privacy interests and personal freedoms."

Review Standards:

-

Objective facts required: Police cannot rely on subjective belief—must provide objectively discernible facts

-

Courts not bound by police conclusions: Independent judicial assessment required

-

Exacting scrutiny: Review must be rigorous where constitutional rights at stake

-

Legitimacy test: Police must show legitimate reasons related to criminality (or, conversely, legitimate reasons for declining investigation)

C. Enhanced Procedural Protection for Significant Harms

Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, para 133:

"It is well established that individuals are entitled to greater procedural protection when the decision in question involves the potential for significant personal impact or harm."

Application: Where police declination to investigate involves:

-

Ongoing serious crimes (harassment, fraud, privacy violations)

-

Significant personal harm (financial ruin, safety risks, health consequences)

-

Constitutional rights (liberty, security, expression, privacy)

Courts apply enhanced scrutiny—requiring clear reasons, engagement with evidence, and justification for declining investigation.

IX. UNREASONABLE CONCURRENCE IS NO DEFENSE

A. Consensus Among Officers Does Not Cure Unreasonableness

Sittampalam Principle (established in Section V.A): Consensus among peace officers, should it fail objective reasonableness tests and fail to withstand reasonable public scrutiny, is no adequate defense.

R. v. Bellusci, 2012 SCC 44, [2012] 2 S.C.R. 509, para 24:

"The integrity of the justice system was further tarnished, in the judge's view, by the reticence and [translation] 'sclerotic solidarity' that characterized the testimony at trial of Mr. Asselin's fellow prison guards."

"Sclerotic Solidarity": Rigid, unthinking loyalty among institutional actors that protects colleagues despite misconduct—recognized by courts as undermining justice system integrity.

Principle: Where multiple officers or institutional actors coordinate to decline investigation, dismiss complaint, or characterize evidence as insufficient, their agreement does not establish reasonableness. Courts assess:

-

Whether objective, reasonable person would agree

-

Whether solidarity reflects institutional protection rather than independent assessment

-

Whether coordinated response serves justice or institutional interests

B. Institutional Coordination Justifying Stay of Proceedings

R. v. Bellusci, para 25:

"Having found that Mr. Bellusci had been provoked and subjected by a state actor to intolerable physical and psychological abuse, it was open to the trial judge to decline to enter a conviction against him. As the Court explained in Tobiass, 'if a past abuse were serious enough, then public confidence in the administration of justice could be so undermined that the mere act of carrying forward in the light of it would constitute a new and ongoing abuse sufficient to warrant a stay of proceedings.'"

Application: Where police conduct (or coordinated institutional conduct) involves:

-

Serious abuse of process

-

Intolerable treatment of complainant

-

Institutional coordination to prevent investigation

Such conduct may warrant extraordinary remedies (stay of proceedings, exclusion of evidence, civil damages) because continuing despite abuse would further undermine public confidence.

X. PRACTICAL APPLICATION FRAMEWORK

When Does the Duty to Investigate Arise?

Step 1: Identify the Information Provided

-

Documentary evidence (records, correspondence, recordings)

-

Witness statements or complainant account

-

Physical evidence

-

Expert analysis or opinions

-

Timing correlations or patterns

Step 2: Assess Against Reasonable Suspicion Standard

Does information meet Mann/Chehil reasonable suspicion? Required Elements:

-

Objective facts (not speculation or hunch)

-

Connection to specific criminal activity (not general wrongdoing)

-

Articulable basis (can be explained to court)

-

Contextual coherence (facts make sense together)

If YES: Police possess investigative authority (Mann detention, Chehil techniques). Declination requires legitimate justification. At this level, police cannot reasonably say "we had grounds to detain and question, but we chose to do nothing". The information that authorizes intrusive investigation mandates non-intrusive investigation.

Step 3: Assess Against Reasonable Grounds Standard

Does information meet Mugesera reasonable grounds to believe?

Three-Part Test:

-

Objective basis: Would reasonable observer in same circumstances believe grounds exist?

-

Compelling information: Is information substantial (not trivial)?

-

Credible information: Are sources reliable and trustworthy?

Cumulative Assessment:

-

Do multiple facts cohere, creating pattern?

-

Does combination of facts strengthen inference?

-

Would reasonable observer see connection between facts?

Probability Assessment:

-

Does information create reasonable probability that crime occurred/is occurring?

-

Is probability more than negligible, fanciful, or speculative?

-

Would reasonable person in same circumstances believe investigation warranted?

If YES: Police possess coercive authority (arrest, search). Declination objectively indefensible absent extraordinary circumstances.

At this level, the duty is non-abdicable. Investigation is required to fulfill fundamental state function recognized in Beaudry and Hill.

Step 4: Consider Legitimate Reasons for Declination

Even where reasonable suspicion or reasonable grounds exist, declination may be justified by:

-

Resource constraints (more serious crimes requiring immediate attention)

-

Ongoing investigation (would interfere with existing investigation)

-

Jurisdictional issues (another agency better positioned)

-

Safety concerns (investigation would escalate danger)

-

Prosecutorial advice (Crown advises insufficient prospect)

-

Evidentiary barriers (critical evidence legally unavailable)

But declination is not justified by:

-

Institutional solidarity (protecting colleagues/organization)

-

Convenience ("too much work")

-

Animus ("we don't like complainant")

-

Prejudgment ("we don't believe it" without investigating)

-

Circular reasoning ("no grounds because haven't investigated")

What Investigation Does NOT Require:

❌ Proof beyond reasonable doubt

❌ Prima facie case for conviction

❌ Balance of probabilities showing crime occurred

❌ Overwhelming evidence

❌ Complete investigation before beginning investigation

❌ All witnesses interviewed

❌ Suspect's explanation obtained

❌ All possible defenses explored

❌ Legal judgment that charges will succeed

❌ Certainty that crime occurred

What Investigation DOES Require:

✓ Objective basis for belief (reasonable observer test)

✓ Compelling and credible information

✓ Reasonable probability (more than negligible/speculative)

✓ Conscientious and informed decision-making

✓ Acting reasonably in the circumstances

✓ Consideration of cumulative effect of facts

✓ Independent assessment (not bound by institutional solidarity)

✓ Legitimate reasons related to criminality (or legitimate reasons for declining)

XI. SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

A. When Complaint Involves Police Misconduct

Where citizen complaint alleges police misconduct (fabricated reports, investigation declination without legitimate reason, coordination with subjects of investigation):

Enhanced Duty: Courts recognize particular public interest in investigating police misconduct due to:

-

Erosion of public confidence if police investigate themselves inadequately

-

Risk of institutional protection ("sclerotic solidarity")

-

Power imbalance between complainant and police

-

Deterrent value of accountability

Standards Apply Equally: Same reasonable grounds standard applies—but courts will scrutinize whether:

-

Investigation was actually conducted or merely appeared to be conducted

-

Declination was based on legitimate assessment or institutional protection

-

Multiple officers' agreement reflects independent assessment or coordinated deflection

B. When Complaint Contains Multiple Corroborating Elements

R. v. Harding coherence principle applies: Where complaint contains:

-

Documentary evidence (showing contradictions, timing patterns, coordination)

-

Multiple independent facts cohering into pattern

-

Timing correlations suggesting coordination or causation

-

Witness accounts corroborating documentary evidence

Police cannot dismiss each element individually—must assess cumulative effect.

Example from Harding: Individual elements viewed in isolation:

-

BC plates: Common, innocent

-

Large bags: Common, innocent

-

Marijuana smell: Requires investigation

-

Rental car: Common, innocent

Cumulative effect when viewed together: Reasonable grounds to believe drug transportation

Analogous Application to Institutional Misconduct: Individual elements viewed in isolation:

-

Single procedural irregularity: Could be error

-

Timing correlation: Could be coincidence

-

Documentary contradiction: Could be mistake

-

Pattern of institutional declinations: Could be resource constraints

Cumulative effect when viewed together: Reasonable grounds to investigate coordination or misconduct

C. When Institutional Actors Provide Contradictory Accounts

Where police/institutional records contradict:

-

Officer's statements during meeting with complainant

-

Written reports filed afterward

-

FOIPOP-obtained internal communications

-

Public statements about investigation

R. v. Stinchcombe disclosure principles and Vavilov reasonableness review require:

-

Contradictions must be addressed, not ignored

-

Preference for contemporaneous records over later accounts

-

Explanation required where material contradictions exist

-

"Sclerotic solidarity" scrutinized where multiple actors provide mutually supporting but individually contradictory accounts

XII. REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENT INVESTIGATION

A. Civil Action for Damages

Hill v. Hamilton-Wentworth Regional Police Services Board establishes: Police owe duty of care in investigation; negligent investigation actionable where:

-

Duty owed to complainant/suspect

-

Breach of standard of care (failed to act reasonably)

-

Causation (breach caused harm)

-

Damages (actual harm suffered)

Standard: Reasonableness in the circumstances—did police act as reasonable officers would in same situation?

B. Stay of Proceedings / Abuse of Process

R. v. Babos, 2014 SCC 16: Where police conduct involves abuse of process:

-

Oppressive or vexatious conduct

-

Conduct offending court's sense of fair play and decency

-

Undermining integrity of judicial process

Courts may grant stay of proceedings—even if prosecution otherwise valid—because continuing despite abuse would further undermine justice system.

C. Administrative Remedies

-

Complaints to police oversight bodies (disciplinary proceedings)

-

Judicial review of police decisions (mandamus, certiorari)

-

Ombudsman complaints (systemic review)

-

Human rights complaints (Charter violations)

XIII. SUMMARY: KEY PRINCIPLES

1. Police Duty Non-Abdicable: Duty to investigate is fundamental state function that cannot be refused where reasonable suspicion or reasonable grounds exist.

2. Reasonable Suspicion Triggers Investigation Duty: Where objective facts suggest connection to criminal activity (Mann/Chehil standard), police cannot reasonably decline to investigate—the information that authorizes intrusive powers mandates non-intrusive investigation.

3. Reasonable Grounds Creates Near-Absolute Duty: Where objective, compelling, credible information creates reasonable probability (Mugesera standard), duty is non-abdicable absent extraordinary circumstances.

4. Low Threshold by Design: Standards deliberately lower than civil/criminal proof standards—enables investigation to develop evidence before it is lost or destroyed.

5. Objective Assessment Required: Not subjective police belief but whether reasonable observer would believe grounds exist; courts conduct independent review.

6. Cumulative Effect Matters: Multiple coherent facts establish grounds even where each fact individually insufficient (Harding coherence principle).

7. Investigation Develops Evidence: Police cannot refuse investigation because evidence not yet "overwhelming"—investigation creates overwhelming evidence (Hill).

8. Limited Pre-Investigation Requirements: Police need not exhaust all inquiry, interview all witnesses, or obtain suspect's version before investigating (Central Auto Parts).

9. Meaningful Judicial Review: Courts conduct exacting scrutiny—not bound by police conclusions, must independently assess objective facts (Ahmad).

10. Institutional Solidarity No Defense: Consensus among officers does not establish reasonableness if objective assessment would reach different conclusion (Bellusci "sclerotic solidarity").

11. Enhanced Protection for Serious Harms: Greater procedural protection and careful scrutiny where decision involves significant personal impact (Vavilov).

12. Accountability Essential: Public confidence requires police investigate complaints conscientiously—negligence actionable even without malice (Hill).

XIV. CONCLUSION

The legal framework establishes clear thresholds for police investigation duties operating along a spectrum of information quality. At Reasonable Suspicion Level, where citizen provides:

-

Objective facts (not speculation)

-

Suggesting connection to specific criminal activity

-

That can be articulated and subjected to judicial review

Police must:

-

Recognize they possess investigative authority (Mann/Chehil)

-

Exercise that authority reasonably or provide legitimate justification for declining

-

Cannot reasonably say "we had grounds to investigate intrusively but chose to do nothing"

At Reasonable Grounds Level, where citizen provides:

-

Objective, compelling, credible information (Mugesera test)

-

Creating reasonable probability (more than negligible/speculative)

-

That crime occurred or is occurring

Police must:

-

Investigate conscientiously and reasonably

-

Consider cumulative effect of facts (Harding)

-

Not require overwhelming evidence before investigating (Hill)

-

Provide legitimate reasons if declining investigation

-

Act independently (not through institutional solidarity)

Courts Will:

-

Conduct meaningful, exacting review (Ahmad)

-

Assess objective facts independently (Araujo)

-

Not defer to police subjective conclusions

-

Apply enhanced scrutiny where serious harms involved (Vavilov)

-

Recognize accountability essential to public confidence (Hill)

Failure to Investigate Despite Satisfied Thresholds:

-

Breaches police duty under common law (Beaudry)

-

May constitute negligence (civil liability under Hill)

-

May warrant administrative remedies

-

May justify abuse of process findings (Bellusci)

-

Undermines public confidence in justice system

Finally, the Supreme Court of Canada held that the state should accept responsibility for miscarriage due in part to errors and/or negligence in investigation. Per McLachlin C.J. in Hill, Supra, at paragraph 37;

‘As Peter Cory points out, at pp. 101 and 103: If the State commits significant errors in the course of the investigation and prosecution, it should accept the responsibility for the sad consequences. Society needs protection from both the deliberate and the careless acts of omission and commission which lead to wrongful conviction and prison.”

XV. THE PRACTICAL TEST: A SUMMARY

For any complaint, ask these questions in order:

Question 1: Does the information contain objective, articulable facts suggesting someone is connected to specific criminal activity?

-

If NO: No duty to investigate (but police retain discretion)

-

If YES: Proceed to Question 2

Question 2: Would a reasonable, informed observer believe these facts justify at least preliminary investigative steps?

-

If NO: Declination may be reasonable (but must be explicable)

-

If YES: Reasonable suspicion exists—duty to investigate triggered

At this point, police must investigate or provide legitimate justification for declining. The question shifts from "are there grounds?" to "why aren't you investigating?"

Question 3: Does the information go further—creating not just suspicion but reasonable probability through objective, compelling, credible evidence?

-

If NO: Remain at reasonable suspicion level (investigation still required)

-

If YES: Reasonable grounds exist—duty becomes non-abdicable

At this point, declination is objectively indefensible absent extraordinary circumstances (jurisdiction, ongoing investigation, safety, prosecutorial advice).

Question 4: Do multiple facts cohere, creating a pattern that strengthens the inference?

-

Consider cumulative effect (Harding)

-

Assess whether facts support each other

-

Determine whether whole exceeds sum of parts

Question 5: Has police provided legitimate, articulated reason for any declination?

-

Resource constraints (triaged against more serious matters)?

-

Jurisdictional issues (another agency better positioned)?

-

Safety concerns (investigation would escalate danger)?

-

Prosecutorial advice (Crown advises insufficient prospect)?

Or an illegitimate reason?

-

Institutional solidarity (protecting colleagues)?

-

Convenience ("too much work")?

-

Animus ("don't like complainant")?

-

Circular reasoning ("no grounds because we haven't investigated")?

State-Adjacent Coordination

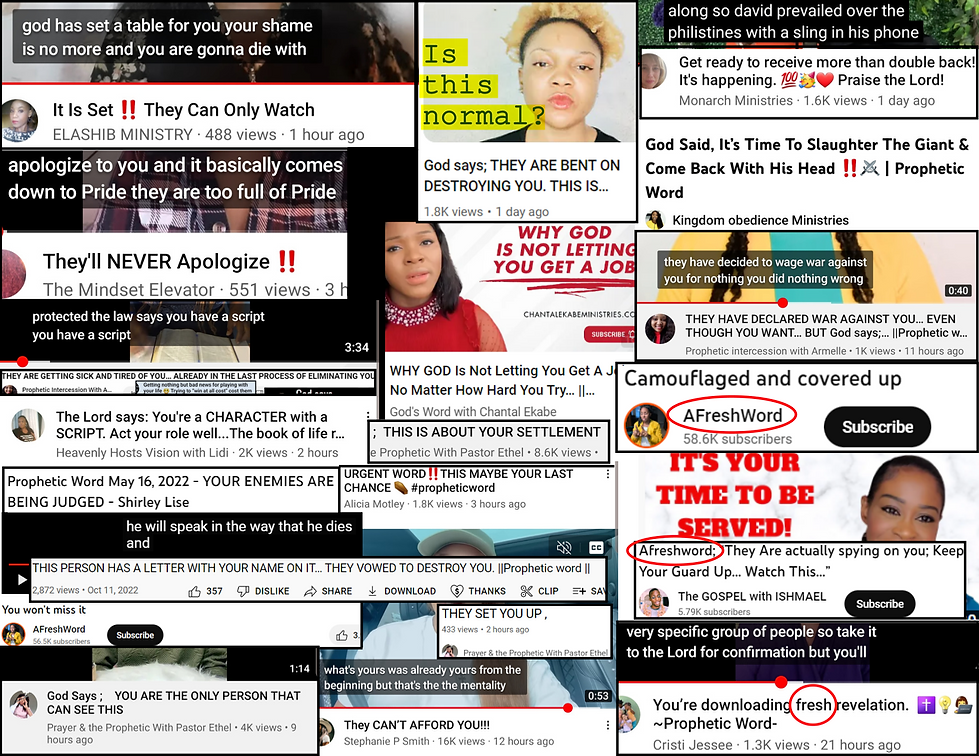

Might These Visuals Engage Police Thresholds, or do they Seem Benign..? (R v. Loewen)

_1.png)

_2.png)

_1.png)

_3.png)

Twenty Million Online Citations

Sheridan does not explore a question of subject credibility in reviewing this data. It does not inquire whether or not the 50 subjects considered in the report are legitimate, or conversely, if the subjects might be delusional. Sheridan achieved its objective insofar as it had identified a glaring data point that, in the opinion of its researchers, merits further study. It can be inferred by the conclusion of the research group that the study's initial dataset of over 20 million citations is robust enough to suggest that there is most likely a significant number of genuine victims.

A Family Connection.

Criminal Mischief, via Algorithm, is Meaningfully Related to Every Event Milestone.

As above per the embellished HRP report that was provided to EHS.

Full details at the HRP Page (Here).

An Example of Finding Reasonable Grounds Concerning the CAGE Entity, and the Likelihood that the CAGE was, and is, the Unlawful Beneficiary of State Interference in the Civil Proceedings.

Irrespective of the choreographed CAGE proceedings (here),

the related criminal mischief (here), and the shareholder scandal (here), a scandal involving retainer fees is among the strongest indicators of third-party interference. The CAGE CEO did not agree to a "reasonable retainer" in the amount of $376,201.97, at 737.7 billable hours (like the passenger jet) to service just nine (9) short hearings under sixty minutes of modest complexity, as paragraph 10 at the October 17th, 2023 Affidavit of counsel Emily MacKinnon had claimed (here). This is satisfied on the fact of its absurdity alone (Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, [2019] 4 S.C.R. 653 at paragraph 104). The Clerks Notes, shown at the same page, invites a customary cost continuum between $7,250 and $12,000 CAD for the entire footprint in BC.

Since this happened to begin with, and because recourse through customary avenues was precluded, one has reasonable grounds then to infer the existence of external tampering, which would likewise require assurances to be provided by stakeholders in position to offer it.

Succinctly, the MacKinnon Affidavits implicate the following persons and entities in a felony crime;

-

The CAGE CEO, because no rational litigant would agree to be billed that retainer, let alone pay it, instead of choosing a different law firm;

-

The CAGE’s BC law firm Osler, Hoskin, & Harcourt LLP, as no reputable law firm would offer an outrageous retainer disproportionate to scope;

-

The adjudicators who signed counsel’s draft certificates in BC, and enforced those costs out of Province, given the legal test in Bradshaw Construction Ltd. v. Bank of Nova Scotia (1991), 54 B.C.L.R. (2d) 309 (S.C.), paragraph 44;

“Special costs are fees a reasonable client would pay a reasonably competent solicitor to do the work described in the bill”;

-

And a plethora of other legal tests concerning fees such as Gichuru v. Smith, 2014 BCCA 414 at paragraph 155;

“When assessing special costs, summarily or otherwise, a judge must only allow those fees that are objectively reasonable in the circumstances”.

-

The Supreme Court of Canada Registry Staff who violated SCC rules 51(1) and 54(4) rules concerning the motions filed in response to stay those costs, and justice Suzanne Côté, for precluding docket entry concerning the leave application without explanation, irrespective of the satisfied test in R. v. C.P., 2021 SCC 19 at paragraph 137;

“There is no basis to believe that a serious argument pointing to a miscarriage of justice would not meet the public interest standard for leave to appeal to the Court [...] The Supreme Court would and does exercise its leave requirement in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.”

An unbiased judge would further recognize that these characteristics are expected to be impossible under ordinary conditions, without the same persons and entities receiving assurances from other persons and/or entities capable of offering them. It is satisfied that the assuring stakeholders would need to occupy a position of overarching power and influence. The remainder of the proceedings exhibit a miscarriage of justice that was likewise denied corrective recourse in every venue. The cost scandal was likewise telegraphed by the online cohort as is shown above. A scandal demonstrating these characteristics across time and venue invites consideration of a post-democratic institutional fabric (here).

A Discovery Avenue is Available Through Tracing Money, Which May Involve Other Assets Like Crypto.

Legitimate Authorities Have Routinely, Unreasonably, & Unlawfully Protected These Criminal Actors.

Courts & Police

Avenues for discovery are available to properly address a framework of transnational organized crime. Access to justice was denied again and again, in every venue, and an Order to introduce the same discovery by a now-retired judge on April 1st, 2022 was obstructed. Canada is a post-democratic state, and powerful interests drive this.

True Audio Transcript

"BEAUTIFUL EVIDENCE" | Implication of CAGE CEO in Criminal Interference & Mischief | Articulation of Next Steps

Official Police Report Obtained via Freedom of Information Request

"LACK OF EVIDENCE" | Pejorative Mischaracterization of Participants | Closure of File

That's what Stakeholder Interference Looks Like.

Case Study: Applying the Tests

R. v. J.F., 2013 SCC 12 at paragraph 53;

“In so concluding, I note that conspiracies are often proved by way of circumstantial evidence. Direct evidence of an agreement tends to be a rarity. However, it is commonplace that membership in a conspiracy may be inferred from evidence of conduct that assists the unlawful object. Justice Rinfret made this basic point in Paradis v. The King, [1934] S.C.R. 165, some eight decades ago: Conspiracy, like all other crimes, may be established by inference from the conduct of the parties. No doubt the agreement between them is the gist of the offence, but only in very rare cases will it be possible to prove it by direct evidence. [p. 168]”

POLICE DUTY TO INVESTIGATE THIS CASE: WHY THE THRESHOLD IS MET AND DISCRETION IS EXHAUSTED

I. QUESTION AND SHORT ANSWER

Question: Do police have a statutory and legal obligation to investigate the facts of this case, and if so, why?

Short Answer: Yes. On the evidence summarized here, the legal threshold of reasonable grounds to believe that multiple Criminal Code offences may have been committed is not just met but substantially exceeded across five interlocking domains:

-

State-adjacent coordination

-

Interference with the administration of justice

-

Psychological operations (PSYOP)

-

Institutional capture

-

Emerging dual-use / neurotechnology concerns as a sensitive, high-risk dimension

Once the customary thresholds are engaged, police discretion concerns how to investigate, not whether to investigate at all. Under the RCMP Act, analogous provincial statutes, and the common-law duty in Hill v. Hamilton-Wentworth, police cannot decline to investigate simply because the pattern is systemic, complex, or implicates institutions.

The combination of:

-

documentary evidence,

-

timing correlations, and

-

statistically implausible patterns

creates a compelling, credible, objective basis that makes investigation a legal obligation, not a discretionary favour.

II. LEGAL FRAMEWORK: WHEN DOES A DUTY TO INVESTIGATE ARISE?

1. Statutory Duty (RCMP Act and Peace Officer Role)

RCMP Act, s. 18 requires RCMP members to:

“perform all duties that are assigned to peace officers in relation to the preservation of the peace, the prevention of crime and of offences against the laws of Canada and the laws in force in any province.”

In plain terms: once there is a reasonable basis to believe Criminal Code offences may have been committed, police are under a duty to take reasonable investigative steps. This is not optional where life, liberty, or serious systemic-integrity issues are at stake. Municipal and provincial forces operate under analogous statutory and common-law duties.

2. “Reasonable Grounds”

Two key authorities define the threshold:

-

R. v. Loewen – Reasonable grounds exist where there is an objectively reasonable belief that an offence was being or had been committed; certainty is not required at that stage.

-

Mugesera v. Canada – Reasonable grounds exist where there is an objective basis for the belief, grounded in compelling and credible information.

This standard is:

-

lower than balance of probabilities;

-

much lower than proof beyond reasonable doubt;

-

a gateway that, once crossed, triggers investigative obligations.

3. Duty to Investigate vs. Negligence

In Hill v. Hamilton-Wentworth, the Supreme Court of Canada:

-

recognized the tort of negligent investigation; and

-

confirmed that once reasonable grounds exist, police must act as a reasonable investigator would in the circumstances.

Police are not entitled to refuse to investigate until evidence is overwhelming. Investigation is the mechanism by which overwhelming evidence is developed.

4. Cumulative Effect and Pattern Recognition

Canadian criminal law recognizes that patterns of circumstantial evidence can be more probative than any single fact:

-

R. v. Harding – The cumulative effect of individually innocuous facts may create a compelling inference of wrongdoing.

-

R. v. Villaroman – Fact-finders must consider whether innocent explanations remain reasonably plausible once the entire pattern is considered.

At the investigative stage, the question is not: “Is guilt proven?”, but: “Does this pattern, taken as a whole, require further investigation by a reasonable officer?”

This is the question this memorandum answers.

III. OVERVIEW OF THE FACT PATTERN

The evidence—largely documentary and independently verifiable—converges in five domains:

-

State-adjacent coordination

Highly anomalous, synchronized responses by courts, regulators, police, and media that consistently prevent examination of shareholder evidence and related irregularities, while enabling enforcement of manifestly disproportionate costs.

-

Interference with the administration of justice

A sustained sequence of judicial and procedural decisions that systematically block discovery, seal records without applying Sherman Estate, and enforce an approximately 9,000% costs markup without scrutiny.

-

Psychological operations / harassment (PSYOP)

A multi-domain campaign (online, physical, cyber, break-ins, “algorithmic” content) that escalated until the complainant was forced into an emergency cross-country evacuation, consistent with patterns identified in cybertorture and “organized stalking” literature.

-

Institutional capture

Over twenty institutions, across multiple jurisdictions and mandates, respond in ways that produce a 100% rate of declination or non-examination of core evidence over four years.

-

Emerging dual-use / neurotechnology concerns

A set of medical, behavioural, timing, and institutional-response anomalies closely tracking risk indicators identified in recent UN reports on neurotechnology, cognitive liberty, and institutional integrity (A/HRC/57/61, A/HRC/58/58, A/HRC/RES/58/6).

Individually, each fact might be explained away. Taken together, they form a pattern that no reasonable police officer can dismiss without investigation.

IV. STATE-ADJACENT COORDINATION

Potential Criminal Code provisions engaged

-

s. 139(2) – Obstructing justice

-

s. 122 – Breach of trust by public officer

-

ss. 423, 423.1 – Intimidation (public or justice-system participant)

-

s. 465 – Conspiracy

-

s. 426 – Secret commissions (if assurances involved financial or professional inducements)

1. Key Facts (Each Arguably Innocent Alone)

Across four years and two provinces, more than twenty touch points (judges, registries, police, regulators, media) produce a uniform practical outcome: probative evidence is never examined, while facially impossible billing is certified and coercively enforced. Core elements include:

-

Massive billing markup

-

~737.7 hours billed for ~14.5 hours of actual court time across nine short BC hearings, plus 89 hours billed for a single 20-minute NS hearing.

-

Aggregate uplift on the order of 9,000% compared to tariff-like expectations.

-

Those amounts were later certified and enforced.

-

-

Court certification without proportionality analysis

-

Certification of this quantum with no meaningful assessment under Bradshaw, Boucher, Gichuru, Okanagan, etc.

-

No attempt to reconcile the billing with the actual procedural simplicity and short hearing times.

-

-

Discovery deflection

-

A proper discovery route opened by Master Cameron (CRA evidence, third-party records) is systematically reversed and then shut down through referral-judge orders, blanket sealing, and summary-hearing acceleration.

-

As a result, shareholder records, FY2020 derecognition, and contradictory affidavits are never independently tested.

-

-

Police declination

-

RCMP non-responsiveness, non-engagement with record, apology but no willingness to correct, subsequent engagement characterized as "harassing communications".

-

Preemptive mental health framing.

-

A 79-minute meeting with HRP where an officer praised the PsyOp evidence as serious and well organized is followed, within five days, by a form-letter declination (“civil matter / insufficient evidence”) and no investigation, with a pejorative mental health tag.

-

Subsequent nonengagement with record, key evidence omitted from FOIPOP reports.

-

Police regulators (CRCC, POLCOM) insulate misconduct.

-

-

Sealing orders beyond the Sherman Estate framework

-

Multiple courts impose blanket or pre-service sealing with no genuine necessity or minimal-impairment analysis, and no serious consideration of redaction, contrary to Sherman Estate, Vancouver Sun, CBC v. New Brunswick, CBC v. Named Person.

-

-

Media removal

-

A Vancouver Sun article referencing aspects of the case is first published, then quietly removed from the website, with no explanation and no further reporting despite repeated outreach.

-

Post Media (Canada-wide) approved creative visuals for RefugeeCanada.Net newspaper ads, signed an ad contract, and accepted payment, but subsequently cancelled the engagement prior to publication through managerial intervention.

-

References to this website appear to be blacklisted and shadow-banned in online forms and social media (test them).

-

Radio stations refusing to air paid advertisements after signing contracts.

-

-

Timing correlations and anticipatory responses

-

Rapid (many < 24-hour) institutional responses that presuppose knowledge of sealed filings or non-public events—for example, affidavits and orders that respond to new sealed content on timelines inconsistent with ordinary internal process.

-

-

Health disregard until external visibility

-

Detailed medical evidence of a serious autoimmune condition is filed and ignored for roughly ten months in the contempt/enforcement track, only to be acknowledged and accommodated the day after a public broadcast email surfaces the same evidence outside the sealed record.

-

-

Registry cooperation in irregular steps

-

Registry staff rubberstamp facially egregious orders, refuse to provide record copies, and violate procedural rules. No whistleblowers.

-

-

Across-the-board institutional declination

-

Every venue contacted—police, securities regulators, law societies, privacy and human-rights bodies, ombuds, courts, politicians, media—either:

-

declines jurisdiction,

-

dismisses without real investigation, or

-

affirms the existing trajectory without engaging the underlying record.

-

-

Alone, each item might be put down to error, editorial choice, resource pressure, or misunderstanding. Together, they form a coherent pattern.

2. Cumulative Pattern and Statistical Improbability

Three features stand out when these events are viewed together:

-

Directional uniformity

Every key decision tends in the same direction: blocking or discouraging examination of the shareholder evidence, billing arithmetic, and PSYOP/neurotech indicators, while enabling and escalating enforcement of the contested judgments (up to and including custody risk).

-

Cross-institutional and cross-jurisdictional persistence. The pattern persists across:

-

time (2021-2025),

-

personnel (multiple judges and officers), and

-

institutions (BC and NS courts, registries, RCMP, regulators, media),

all converging on the same functional outcome

-

Statistical implausibility of random failure

-

Even with a crude 50/50 model (“favourable/unfavourable” to proper examination), the chance of zero favourable outcomes across 20 independent decision points is <1 in 100,000. The exact figure matters less than the intuition: this is not what random or uncoordinated error looks like.

Under Villaroman, Loewen, and Mugesera, a circumstantial pattern that is both:

-

highly unlikely on innocent assumptions, and

-

entirely consistent with coordination,

is precisely the kind of signal that triggers a duty to investigate.

This pattern also matches the “coordination through declination” profile highlighted in the UN Special Rapporteur reports on neurotechnology and institutional integrity (A/HRC/57/61, A/HRC/58/58) and General Assembly resolution A/RES/58/6.

3. Specific Indicators of Informal Coordination

Beyond the overall pattern, several discrete events point directly to informal information-sharing and state-adjacent assurances:

-

RCMP Mental Health Unit designation (11 Feb 2022)

An RCMP officer attends a pre-arranged meeting wearing Mental Health Unit insignia before any court filing or medical assessment has raised mental-health issues. This implies prior informal characterization of the complainant and access to information or narratives outside open proceedings.

-

Pre-service sealing (26–27 Jan 2023)

The Charter proceeding S-229680 is sealed before the petitioner even learns it exists. Registry staff later confirm that sealing pre-dated his awareness. Under Sherman Estate, sealing is supposed to follow notice, submissions, and a necessity/minimal-impairment analysis. The timing suggests behind-the-scenes coordination to suppress potentially exculpatory or embarrassing material.

-

Pre-drafted reversal orders (24 May 2022)

Just 53 days after Master Cameron opens a CRA-based discovery route, a referral judge unfamiliar with the file is presented with a pre-drafted summary/acceleration order that effectively extinguishes that discovery pathway, with no articulated reasons. Drafting a reversal order in advance of argument suggests foreknowledge that this would occur.

-

Anticipatory responses to sealed filings

In at least one instance, a sealed affidavit is filed on Day 1, and by Day 2 a protection-order application appears directly addressing its key contents—on a timeline incompatible with ordinary access, review, drafting, commissioning, and filing. The only realistic possibilities are improper access to sealed materials or real-time monitoring of court activity.

-

Health-response timing as operational “tell”

Comprehensive autoimmune documentation sits in the court file for about ten months with no sign of judicial engagement. Within 24 hours of a public broadcast email surfacing the same health evidence outside the sealed record, the court acknowledges the diagnosis and softens the custodial risk. This strongly suggests reputational visibility, not legal merit, drove the response.

Each of these events supports an inference that informal channels—not just formal filings—are shaping institutional responses.

4. The 9,000% Billing as Operational Architecture

The billing pattern cannot credibly be explained by ordinary “hard-fought litigation”:

-

~737.7 hours billed vs. ~14.5 hours of actual court time in BC (short chambers matters using standard forms).

-

89 hours billed for a single 20-minute NS hearing.

-

Approximately $400,000 in total fees where tariff-style benchmarks would suggest ~$4,500–$6,000.

For this to occur:

-

No rational client accepts that quantum unless they are highly confident that:

-

the bills will be certified without proportionality review;

-

cross-provincial enforcement will be granted;

-

contempt and possibly custody will be used to coerce payment; and

-

the billing will never be forensically examined.

-

-

No rational court certifies such amounts unless it is effectively confident that:

-

higher courts will not seriously scrutinize proportionality; and

-

public exposure will be contained (e.g., via sealing, dismissal of complaints).

-

This implies a chain of expectations and assurances:

Firm → Trial courts → Enforcement judges → Appellate courts → Registries/administrative gatekeepers → Media/public-facing actors

That chain is not a speculative flourish; it is a necessary precondition for the behaviour actually observed. It is therefore evidence in itself, justifying questions such as:

-

What understandings, if any, were communicated about this file?

-

Who knew what, and when, about the billing, sealing, and enforcement strategy?

-

Were any public officers or state-adjacent actors encouraged, induced, or assured that departures from ordinary standards would be protected?

5. Result: Reasonable Grounds for State-Adjacent Coordination

Taken together—the billing, discovery deflection, sealing practices, RCMP and regulatory declinations, registry behaviour, media removal, timing correlations, and health-response pattern—there is an objective, compelling, and credible basis to suspect that:

-

state and/or state-adjacent actors have coordinated, informally or covertly, to shape institutional outcomes in this matter; and

-

that coordination may engage offences including obstruction of justice (s. 139), breach of trust (s. 122), intimidation of a justice participant (ss. 423, 423.1), conspiracy (s. 465), and possibly secret commissions (s. 426) if assurances were tied to material benefit.

Under Loewen, Mugesera, and Canada’s UN-level obligations (A/HRC/57/61, A/HRC/58/58, A/HRC/RES/58/6), this pattern clears the reasonable-grounds threshold. It is no longer open to police, in good faith, to dismiss these concerns as “civil” or “speculative” without a proper criminal investigation into the coordination itself.

V. INTERFERENCE WITH THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE

Potential offences

-

Criminal Code s. 139(2) – Obstructing justice

-

Criminal Code s. 463 – Attempt

-

Criminal Code s. 465 – Conspiracy

-

Criminal Code s. 380 – Fraud

-

Criminal Code s. 131 – Perjury

The conduct here centers on two linked mechanisms:

-

A sustained, multi-judge deflection of discovery after a court had already found it necessary; and

-

A pattern of sealing orders that depart from Sherman Estate and function to keep that same evidence permanently out of public and adversarial view.

Both tracks have the practical effect of preventing core evidence from ever being tested, which is the essence of interference with justice—whether successful (s. 139(2)), attempted (s. 463), or concerted (s. 465). They also map directly onto the type of institutional foreclosure flagged by the UN Special Rapporteurs on neurotechnology and institutional integrity (A/HRC/57/61, A/HRC/58/58; A/HRC/RES/58/6).

1. Discovery Deflection Following Court Order

On 1 April 2022, Master Cameron issued a reasoned order authorizing CRA discovery, expressly recognizing that:

-

the shareholder-record issues (CSR freeze, FY2020 derecognition, unexplained transfer/POA) could not be resolved on affidavits alone;

-

independent third-party evidence from CRA and related entities was necessary to test the company’s and CEO’s claims; and

-

such discovery was legally grounded in Slattery, Hryniak, Teal Cedar, Spar Aerospace, etc.

From that point, the file should have moved along a proportionate, evidence-developing track. Instead, a one-way deflection unfolded:

-

24 May 2022 – Tammen J.

-

Extends blanket sealing order in an ensconced hearing.

-

Signs a pre-drafted order permitting the CAGE to seek "any type of relief" that might contrast with the Cameron order.

-

Practical effect: Structural preemptive support for the procedural foreclosure that followed.

-

-

27 June 2022 – Tucker J.

-

Issues a blanket sealing and protection order on the grounds that the Petitioner had intended to serve court documents extrajudicially; requiring Petitioner to seek leave (permission) to execute the April 1 2022 order's terms.

-

Order was issued on an allegation the CAGE raised which they admitted was speculative in the same hearing, and despite a written agreement between parties concerning the Cameron order.

-

Practical effect: relitigated April 1 2022 order, and reconfigured the tone of the proceedings.

-

-

12 Aug 2022 – MacNaughton J.

-

As referral judge, states limited familiarity with the broader file yet dismisses the CRA route and accelerates to a summary hearing.

-

Offers no careful explanation why discovery previously found necessary is now unwarranted.

-

Signs pre-drafted orders that directly conflict with the Cameron mandate.

-

Practical effect: Procedural roadmap is effectively derailed.

-

-

13 Sept 2022 – DeWitt-Van Oosten J.A. (BCCA)

-

Refuses a stay to pause summary disposition and allow proper evidence development, and interlocutory appeal of MacNaughton order.

-

Does not engage with the systemic issue that the evidence-testing mechanism identified as necessary is being dismantled step by step.

-

Closed chambers immediately when ITA 241 (3.1) was raised concerning a lawful tax record discovery avenue of AI-assisted contractors related to the proceeding.

-

Practical effect: Appellate-level foreclosure of procedural roadmap; the file moves forward without CRA and third-party materials.

-

-

4 Oct 2022 – Crossin J.

-

Authorizes summary petition to move forward in absentia.

-

Ignores legal test, and the discovery order that remains outstanding.

-

Practical effect: A clear concurrence among adjudicators to suffocate the proceedings through procedural foreclosure.

-

-

8 Nov 2022 – Majawa J.

-

Characterizes the shareholder-record evidence as “likely irrelevant” because the CSR is “not part of the Settlement Agreement”, and dismisses the petition.

-

Wrongly claims the Tucker order was correct because Petition materials were disclosed (they were not).

-

Does not explain why Cameron’s earlier conclusion that third-party evidence was necessary has been effectively nullified, contrary to Vavilov’s requirement to “meaningfully grapple” with key issues and prior analysis.

-

Practical effect: Ignores hard evidence, prior adjudicative validation, and applicable case law to close the matter.

-

Features of concern:

-

Unidirectionality – Every step moves away from discovery and transparency; no judge restores or even partially implements Cameron’s order.

-

Non-engagement with prior reasoning – None of the subsequent judges grapples with Cameron’s reasoning or explains why it is being abandoned, contrary to Vavilov.

-

Compressed timing and shortcuts – The reversal unfolds rapidly via pre-drafted orders, blanket sealing, accelerated summary hearing, and an in-absentia appearance, despite documentary contradictions and credibility issues that ordinarily counsel more evidence, not less.

On a cumulative view, this not “hard luck” or random judicial variation. It is a multi-actor pattern whose practical effect is to ensure that the shareholder evidence is never properly examined after a court had already said it must be. Under Villaroman, Harding, and Loewen, such a pattern requires explanation and can support an inference of obstruction or coordinated deflection. At the investigative stage, it easily clears the reasonable-grounds threshold.

Continued review of the proceedings in BC 2023, the enforcement hearings NS, and the SCC leave to appeal / certiorari attempt, which continue this track, are available through the Litigation portal (here).

2. Sealing Orders and Non-Compliance with Sherman Estate

Running parallel is a multi-year sequence of sealing and publication-control measures in both BC and NS. Across these decisions:

-