Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act (S.C. 2000, c. 24) [Link]

The Cost Scandal Affidavits [8,258% Above Tariff]

Assurances, coordination, and a convincing narrative were required to orchestrate a scandal that courts have refused to correct.

1582235 Ontario Limited v. Ontario, 2020 ONSC 1279 at paragraph 27;

“In Enterprise Sibeca Inc. v. Frelighsburg (Municipality), the Supreme Court described bad faith as “acts that are so markedly inconsistent with the relevant legislative context that a court cannot reasonably conclude that they were performed in good faith.”

March 3rd, 2025

A Felony Facilitated Through Recognized Public Authorities.

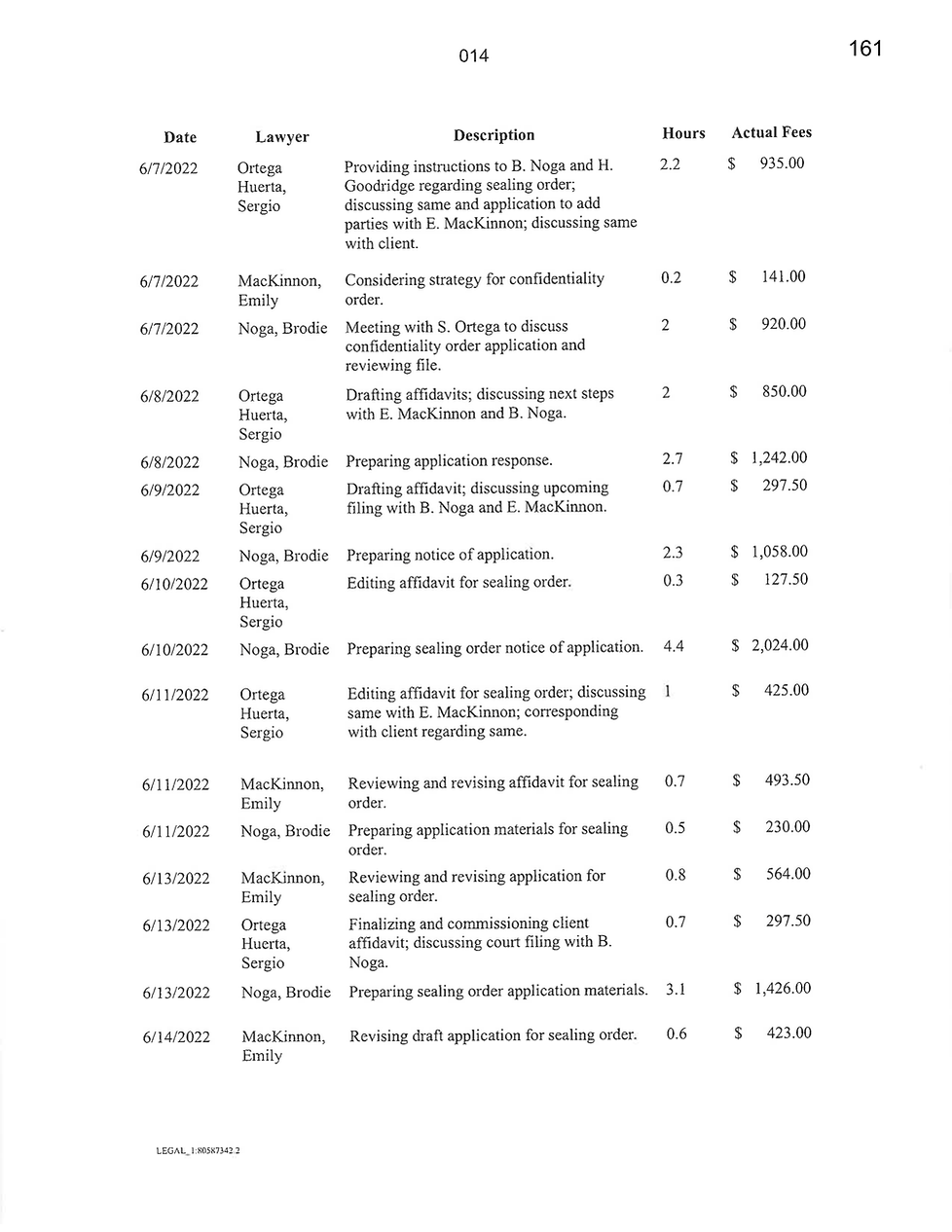

Supplemental to the litigation contents (here), this blog page exhibits true redacted copies of the October 17th, 2023 Affidavits of Emily MacKinnon, lead counsel for the unidentified and federally-sponsored Commercial and Government Entity ("CAGE") referenced on this website.

Retainer fees (lawyer costs) in the amount of $376,201.97 were certified in British Columbia in response to nine (9) court hearings under 60 minutes in duration, as shown in the BCSC Court Clerk’s Notes, likewise depicted at this page. These hearings were of simple complexity and were often handled by articling students. The bill reflected 737.7 hours of work (like the passenger jet), with the line items depicting seven (7) lawyers and two (2) paralegals assigned to overlapping tasks at outrageous time blocks. The same pattern had occurred in the BC Court of Appeal. By contrast, customary tariffs reside in the neighborhood of $500 for a hearing under one hour (ie., NS Rule 77), which reflect industry standards, or, $4,500 for all nine hearings by comparison. The BC certificates followed the miscarriage of justice shown (here).

The bill was enforced outside BC in the form of an execution order, without any regard for the circumstances. None of the aspects of the scandal were corrected through customary recourse nor investigated, despite my best efforts. Docket entry was denied at the SCC. The entire file was permanently sealed in all venues, and the courts had in fact published a revised chronology of events.

The proceedings were further beset by AI-Assisted cyber torture, Influence Ops, and neurotech crime (here & here), in the ambit of UN Resolution A/HRC/57/61, as is detailed in the Testimony. This page focuses on the destructive retainer fee scandal which exceeds the remainder of my nest egg.

Assurances Were Given.

The relationship between the MacKinnon Affidavits and the BCSC Clerk's Notes invites consideration of a third-party project interest alongside the other aspects of the scandal. The analysis is easy. A reasonable litigant would not agree to a $400,000 retainer to conduct nine short hearings with modest prep, many of which were expected to be handled by articling students. A reputable law firm (Canada’s 4th largest) would not propose that retainer. An unbiased adjudicator would neither certify nor enforce it. Finally, the various employees and public servants sandwiched between the milestone events could not be expected to violate their mandates and personal ethics in assisting an effort like that under ordinary conditions, whereas in certain capacities, they had.

These characteristics, widely disproportionate to the commercial interests of a mid-sized company, and antagonistic to the public’s expectation of an independent judiciary, cannot occur in a vacuum. They require a shared purpose among participants, and an environment capable of managing risk that the CAGE could not provision as an independent actor. Prior to any initial steps being taken, the persons and entities involved would have required assurances from a stakeholder capable of offering them. Coordination and contingency planning would be required to ensure continuity among stakeholders and adjudicators in other venues. Finally, the benefit of aligning with the scandal would have been understood to eclipse any risks in the ambit of the criminal code. These are exceptionally high thresholds with a lot of boxes to tick, and they yield an exceptional proportionality gap when measured against the CAGE's private commercial interests alone.

In other words, none of the persons and entities involved would have agreed to move forward in that capacity unless they were certain that the courts would rule in such a way as to permit the scandal, and that both federal and provincial law enforcement, and regulators, would turn a blind eye. The scandal could have gone anywhere. Consider what that means with respect to the scope of a controlled institutional framework.

It is thus reasonable to conclude the existence of a robust third-party project interest, and systemic characteristics in Canada's institutional fabric that widely detract from public expectation. A bald denial of contextual evidence and a reliance on unfounded jurisdictional excuses, both thematic to the management of the scandal, invite diminishing returns. The only things that protect perpetrators at present are unconstitutional sealing orders, and a reticence among police and professional colleagues. A whistleblower will not only address the injustice shown on this website; he/she will address an unconstitutional framework that undermines the standards Citizens have voted for and pay taxes to maintain.

An Uncontroverted Case Law Mandate.

The case law concerning costs is clear. Per Bradshaw Construction Ltd. v. Bank of Nova Scotia (1991), 54 B.C.L.R. (2d) 309 (S.C.) at paragraph 44;

"Special costs are fees a reasonable client would pay a reasonably competent solicitor to do the work described in the bill.".

Likewise per Gichuru v. Smith, 2014 BCCA 414 at paragraph 155;

“When assessing special costs, summarily or otherwise, a judge must only allow those fees that are objectively reasonable in the circumstances”.

Other tests align, and include but are not limited to Grewal v. Sandhu, 2012 BCCA 26 at paragraph 106; Smithies Holdings Inc. v. RCV Holdings Ltd., 2017 BCCA 177 at para. 56; Nuttall v. Krekovic, 2018 BCCA 341 at paragraphs 26 & 29; and Tanious v. The Empire Life Insurance Company, 2019 BCCA 329 at paragraphs 49 & 53, inter alia.

By way of further analogy, Northmont Resort Properties Ltd. v. Golberg, 2018 BCSC 151 had determined special costs in an amount of $333,000 for three hundred and seventy (370) actions, being $900 per action, at paragraph 50. I was billed $376,201.97 for just nine (9) thirty-minute hearings (very short actions), and was denied customary recourse. That's an average of $41,217.53 per action in my case, which paragraph 10 in the MacKinnon Affidavits state were reasonably required, and were billed to the CAGE. The one twenty-minute hearing in S-229680 was billed at $78,385.36, which exceeds current data concerning Canada's average annual salary of $59,020 at the time of this update (source here).

Having exhausted my recourse in August 2024, I was jailed for thirty days for opposing it (here), whereas the court refused to recognize Wilson J.'s valid legal defense promulgated in Perka v. The Queen, [1984] 2 S.C.R. 232, or acknowledge any of these facts for that matter. At the time of this July 6th, 2025 update, I was advised by a judge that I may face subsequent incarceration again in the near future. The contents at the "jailed" page likewise contain redacted health records.

A scandal such as this is expected to be corrected with aplomb, including at the SCC level. Per R. v. C.P., 2021 SCC 19 at paragraph 137;

“There is no basis to believe that a serious argument pointing to a miscarriage of justice would not meet the public interest standard for leave to appeal to the Court [...] The Supreme Court would and does exercise its leave requirement in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.”

It is again noted that these costs arrived on the heels of a miscarriage of justice, which is explored at the Litigation page and the Civil page in a loosely chronological fashion, as supported by redacted exhibits, preceded by the shareholder scandal shown (here). The entirety of the scandal must be addressed, as to explore the cost component alone would signal acceptance of the miscarriage of justice that led to it. The RCMP has not yet agreed to investigate this scandal in any of its related parts, be it the related criminal interference, or the collusive effects cited here, despite an obvious appearance of scandal, and the latter being actionable under Part IV of the Criminal Code.

R. v. Tayo Tompouba, 2024 SCC 16 at paragraph 72;

"..miscarriages of justice under s. 686(1)(a)(iii) Cr. C. are a residual category of errors that exists to ensure that a conviction [translation] “can be quashed where a trial was unfair, regardless of whether the error was procedural or substantive in nature” (Vauclair, Desjardins and Lachance, at No. 51.250; see also Khan, at paras. 18 and 27). The question to be decided in this regard is whether the irregularity was so severe that it rendered the trial unfair or created the appearance of unfairness (Khan, at para. 69, per Lebel J., concurring; see also Fanjoy, at pp. 238‑40; Davey, at paras. 50‑51; Kahsai, at paras. 67‑69)."

R. v Wolkins, 2005 NSCA 2 at paragraph 89;

“A miscarriage of justice may be found where anything happens in the course of a trial, including the appearance of unfairness, which is so serious that it shakes public confidence in the administration of justice: R. v. Cameron (1991), 1991 CanLII 7182 (ON CA), 64 C.C.C. (3d) 96 (Ont. C.A.) at 102; leave to appeal ref’d [1991] 3 S.C.R. x.”

The First Cost Gouge Occurred in the BC Court of Appeal | a 73x Multiplier

Comparing the Scope and the Results.

The cost gouge pattern began in early 2023 in the BC Court of Appeal. This visual depicts a side-by-side comparison between a BCCA motion, and a motion of equal scope and complexity in the out-of-province enforcement proceedings. Both motions involved modest prep that resulted in an 11-page brief filed by CAGE counsel in each. Both resulted in 20-minute hearings. The BCCA matter was billed at $36.726.29; over seventy three times (73x) the costs in the out-of-province motion at $500. The transcript and subsequent correspondence with the BCCA Registrar contains veiled references to the mathematical delta. Readers will note the 737.7 hours shown in the BCSC MacKinnon Affidavits might be dubbed a "cost delta", in reference to the passenger airliner and the "Bow-wing" 737-700 aircraft. CAGE lead counsel Emily MacKinnon is a uniformed legal advisor to the Canadian Military (see further reference in the Guide). The scandal is suffused with dog whistles.

2021 Settlement Payout: "You're Getting Back What's Yours". [PsyOp Guide] | Cost Gouging

CAGE Director

The Affidavits

S-220956

Court Hearings in S-220956 (Nine Short-Chambers Appearances, one Short Paper Application)

[1] February 11th, 2022. Interim sealing order. Judge orders my 2021 CAGE Affidavit into the file. 10 minute hearing. No costs to either party.

[2] March 3rd, 2022. Interim sealing order (extension). 30 minute hearing. No costs to either party. Legacy materials used.

[3] April 1st, 2022. Acknowledgement of fraudulent commercial records and perjury in the CAGE Settlement Affidavit. Order to serve Canada Revenue Agency with all court materials. Parties ordered to seek direction on how ("how", not "if") to serve three private entities related to the 2021 CAGE shareholder oppression matter. 40 minute hearing. No costs to either party.

[4] April 14th, 2022. Request to allow a local process-serving agent to retrieve orders in the file. 17 minute hearing. No costs to either party.

[5] May 24th, 2022. Interim sealing order. 20 minute hearing in private room, in violation of BCSC Rule 22-1(5) . No costs to either party. Legacy materials used.

[6] June 27th, 2022. Protection order hearing based on a false accusation by the Respondents that I had served third parties without obtaining direction from the court on method. Ms. MacKinnon admitted at the hearing that the same was a speculative concern. 30 minute hearing in private room, in violation of BCSC Rule 22-1(5). Respondents awarded costs in the cause, and a protection order was made atop an existing sealing order, thereby requiring me to seek the permission of a judge to execute the terms of the April 1st, 2022 order (res judicata).

[7] August 12th, 2022. Referral judge allows Respondents to re-litigate the April 1st, 2022 order, and approves a summary hearing of the Petition without the required forensic audit (res judicata). Signs the Respondents' pre-drafted order. 30 minute hearing. No mention of costs in the order.

[8] September 27th, 2022. Judge schedules summary Petition hearing irrespective of the outstanding discovery order (res judicata), after a BC court of appeal hearing rejected a motion to stay the execution of the summary hearing date, while an appeal of the August 12th 2022 order was being pursued. 5 minute hearing. Legacy materials used. No mention of costs in the order.

[9] October 4th, 2022. Justice Andrew Majawa dismisses S-220956 in a miscarriage of justice tantamount to what one might expect in a kangaroo court. He ignores proof of fraud, perjury, and evidence of collusion, and he ignores the outstanding discovery order. By way of irony, he is the same judge that ordered the investigation of a solicitor's trust accounts on the basis of a hunch (A Lawyer v The Law Society of British Columbia, 2021 BCSC 914 at paragraph 63). Awards Respondents special costs, which by definition, are commensurate with customary retainer fees (Bradshaw, Supra). Seals entire file permanently. Hearing was one hour in duration.

[10] November 7th, 2022. Justice Majawa dismisses my paper reconsideration motion, being privy to an Affidavit that treated his reasons line by line with the facts and case law. CAGE counsel emailed his decision several days later.

Why would the CAGE CEO agree to pay a retainer in the amount of 580.8 hours at $295,581.11, knowing that customary tariffs are pennies by comparison (ie., $500 per)? The answer is he wouldn't. It is a felony facilitated through legitimate authorities. In Canada.

S-228567

Court Hearing in S-228567 (One Short-Chambers Appearance)

[1] November 8th, 2022. Interim sealing order. This was contested, by way of contrast to the Affidavit. The one Affidavit in this file was limited to public visual exhibits, similar to those on the Zersetzung page. Judge wrongly claimed the file contained shareholder information, which would not be able to be sealed in any event (Sierra Club of Canada v. Canada (Minister of Finance), [2002] 2 S.C.R. 522, 2002 SCC 41 at paragraph 55). 10 minute hearing. No costs to either party. The CAGE later claimed a customary tariff of $1,616.60. This file was discontinued as it was a Charter class action that was brought under the incorrect Style of Proceeding, as a Petition.

S-229680

Court Hearing in S-229680 (One Short-Chambers Appearance)

[1] February 14th, 2023. Summary dismissal by BCSC chambers judge Andrew Majawa; the same who had dismissed S-220956. Upon an emailed request of Loretta Chun, counsel for the Attorney General of Canada, the BCSC discarded nine (9) rules of procedure that governed the Style of Proceedings, after BCSC scheduling confirmed that a Case Management Judge would be assigned, as was required under BCSC Practice Direction 5. This file, in all respects except the format, was a duplicate of the aforementioned S-228567, and contained the same filing materials. Justice Majawa dismissed the matter in ten (10) minutes, declared me vexatious for the duplicate (which CAGE counsel requested), ordered a permanent sealing order over both files, blocked my participation in any BC court henceforth, and ordered special costs. The hearing was billed at $78,385.36, which is comparable to a good annual salary in Canada. As mentioned, S-228567 and S-229680 were of essentially the same substance, except for the label on the front page of the pleadings. 156.9 hours or $78,385.36 vs. $1,616.60 for the standard tariff. Why would the CAGE CEO agree to that retainer? The answer is he wouldn't. It is felony facilitated through legitimate authorities. In Canada.

BCSC Clerks Notes

Short-Chambers Hearings With Modest Filings

These hearings concerning the Affidavits above were of the same complexity, and whereas, the hearings that required more work were brushed aside quickly by referral judges who knew nothing about the file, and sometimes in private rooms. Mr. Garton was an Articled Student during the initial hearings, albeit seven (7) lawyers and two paralegals (2) from Osler, Hoskin, & Harcourt LLP were assigned in overlapping capacities. If we consider the cost division in S-220956 at parity, each hearing would have been billed at $41,217.53, which is more than what some Citizens in Canada earn on an annual basis. A standard tariff schedule is shown below. Most of these hearings are within the $250 to $500 range apiece. I had participated in each by way of physical appearance and/or through written submissions, with the exception of the extrajudicial sealing order on December 13th, 2022 in S-229680. By means of the Clerk's Notes, and irrespective of the scandal as shown at the Shareholder and Civic pages, customary costs would range between $7,250 and $12,000 for all three BCSC action numbers; not a half-million-dollar felony.

Finally, we must recall that paragraph 10 in the MacKinnon Affidavits state that the CAGE CEO was billed the amounts shown in the same Affidavits and had paid them, which is as equally relevant as the cost amounts themselves. It must be assumed that Osler, Hoskin, & Harcourt LLP had received assurances that a scandal such as this would proceed unanswered. There is absolutely room for error in declaring that a felony that was facilitated through legitimate authorities, which was subsequently denied correction.

S-229680

Replaced S-229567. It is the Correct

Filing Format: a Claim under the CPA.

Comparison With the CAGE Out-of-Province Retainer Fees

Same Manner of Hearings, Costed 83x (83 times) Higher in British Columbia

The Out-of-Province collection enforcement proceedings provide another powerful data point concerning the BC retainer fee scandal. We see this in comparing the time and materials involved in similar appearances between Provinces. Side-by-side, we see thirty-minute hearings with comparable paper filings and review. The cost metric is shown to be 83 times higher in BC for the same work. An Affidavit excerpt from an out-of-province CAGE solicitor is shown below. One overarching matter required four (4) hearings to complete; roughly half of S-220956. That overall matter was billed at $2,500, but counsel's claimed fees were $6,518.50, or $1,629.62 per hearing; an immense departure from the outrageously inflated fees in British Columbia. It is worth noting however that the manner of obstruction in the out-of-province proceedings was comparable to BC, and whereas the BC cost scandal was enforced without anyone batting an eyelash. See the Litigation page for details.

Supported Through Cyber Torture

S-220956

Assurances Were Required for the Cost Scandal... and to Insulate Related Criminal Actors.

As detailed in the Testimony, Guide, and Q/A pages, the BC civil proceedings, which I had no intention of opening under the conditions described, are an enablement component of the scandal described on this website. The scandal is not primarily about a private shareholder dispute with a federally-sponsored CAGE entity, nor the latter with peripheral criminal mischief orchestrated by that CAGE. A CAGE entity cannot be expected to shape the conduct of five courts and three police agencies across three provinces to support its commercial interests. Likewise, an emerging CAGE cannot be expected to retain an online criminal framework that uses algorithms and direct cyber intrusions for any length of time. The CAGE is a participatory agent in a scandal involving robust third-party interests involving 4IR technologies (see 4IR Portal). The same is true of Osler, Hoskin, & Harcourt LLP, Ms. MacKinnon, who is a uniformed legal advisor to the Canadian Military, her colleagues, and the participatory stakeholders in various agencies.

As is detailed in the Guide page, and partially in the Review page concerning reasonable grounds, the bad actors in this scandal are understood to have real-time access to my biometric data, presumably through a remote graphene quantum-dot (GQD) interface (see 4IR Portal, and United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/HRC/57/61). The actors depicted below regularly use event milestones as vehicle of harassment, as well as sundries germane to my day-to-day activities. This has been ongoing since December 2021 in acute capacities, shortly following the close of the initial CAGE settlement, though an evidentiary footprint extends back to 2013 as is detailed in my Testimony. Absent a collusive framework coupled with robust interests, investigators might be hard-pressed to explain how and why a plethora of public service agencies would dispense with their Constitutional mandates to support the interests of one man that runs an emerging tech company, with the help of approximately fifty (50) scripted social influencers, with one of them being the biological mother of my estranged Nephew (Ms. Partrick; "My Father Is Joy"). There are too many irons in the fire, and there is no analogue in case law or common sense concerning the retainer fees that were certified.

The visual exhibit below highlights the issue of overlapping counsel ("look for the overlap, your talent is multiplying, wanted you quieted, it's payback time", etc.) with corresponding timestamps, which BCSC Master Scarth acknowledged, before nonetheless signing the pre-drafted cost certificates provided by counsel. The exhibit below that concerns my frozen bank account ("icing on the cake, lump sums, wealth of the wicked, cashing out, huge payback, god is breaking the rules for you", etc.), likewise with time stamps. Whereas most every major milestone is categorized with similar examples, a cumulative pattern should be readily obvious to investigators. As is contemplated at the CRCC and Q/A pages, the fact that police continue to meet a scandal with this much substance with false reporting and negligence is indicative of collusion.

The scandal likewise raises serious questions concerning a mode of centralized, or multi-stakeholder governance, as is treated in UN documents.

R. v Wolkins, 2005 NSCA 2 at paragraph 89;

"..there can be no “strict formula to determine whether a miscarriage of justice has occurred”: R. v. Khan, 2001 SCC 86 (CanLII), [2001] 3 S.C.R. 823 per LeBel, J. at para. 74 [...] A miscarriage of justice may be found where anything happens, including the appearance of unfairness, which is so serious that it shakes public confidence in the administration of justice: R. v. Cameron (1991), 1991 CanLII 7182 (ON CA), 64 C.C.C. (3d) 96 (Ont. C.A.) at 102; leave to appeal ref’d [1991] 3 S.C.R. x."

R. v. Harding, 2010 ABCA 180 at paragraph 10

"The cumulative effect of all these circumstances was sufficient to provide the objective basis for the arrest which then ensued. Sgt. Topham’s subjective belief in his grounds for arrest was clearly established and was objectively seen and established under the circumstances.”

Enforced in a Contextual Vacuum

The Cost Scandal was Based on an Overlapping Allocation of Billable Hours at Egregious Time Blocks...

...But CAGE Counsel in the Enforcement Court Wrongly Claimed it Was Compensatory.

As shown in the annotated email correspondence in the previous section dated June 28th, 2023, a bill of costs was issued via that email, which was later signed by BCSC Master Scarth carte blanche on November 16th, 2023. The exact same data is reflected in the Affidavits of Emily MacKinnon above in the first section. Paragraph 10 in each Affidavit states that the line items in the same Affidavit were "reasonably required".

Whereas a delta involving 737.7 billable hours shown in the Affidavits and the 867 minutes shown in the BCSC clerks notes is indefensible on the basis of the case law and common sense, CAGE counsel in the out-of-province enforcement court attempted to position the cost scandal as a compensatory award in positioning me as a bad actor. CAGE Counsel below refers to BCSC files S-220956, S-228567, and S-229680, treated (here), whereas I had filed S-228567 as a charter matter alongside an appeal of S-220956, but was asked, ironically, by the CAGE to re-file S-228567 as a "Claim", because the different relief it sought could not be brought as a "Petition". Justice Andrew Majawa declared me a vexatious litigant on these grounds, which are objectively false in their own right. The out-of-province CAGE counsel sought to argue that a $300,000 fine is justified when a self-represented litigant submits a file initially under an incorrect format. The judge held that because it was not her role to review the cost certification, she would be permitted to adjudicate a motion concerning its enforcement in a contextual vacuum.

Amid Seeking Corrective Recourse...

...I Sought a Stay of Proceedings.

As is detailed (here), I applied for a stay of proceedings on the basis of section 8 of the Enforcement of Canadian Judgments and Decrees Act, whereas I was in the midst of seeking corrective remedy at the Supreme Court of Canada. Since the legal basis for such a motion was satisfied, an order to stay the proceeding would be discretionary in nature. A stay of proceedings is a discretionary decision. Every fact must be considered, including the outrageous facts detailed above. Per Colburne v. Frank, 1995 NSCA 110 at paragraph 9;

"...Under these headings of wrong principles of law and patent injustice an Appeal Court will override a discretionary order in a number of well‑recognized situations. The simplest cases involve an obvious legal error. As well, there are cases where no weight or insufficient weight has been given to relevant circumstances, where all the facts are not brought to the attention of the judge or where the judge has misapprehended the facts. The importance and gravity of the matter and the consequences of the order, as where an Interlocutory application results in the final disposition of a case, are always underlying considerations. The list is not exhaustive but it covers the most common instances of appellate court interference in discretionary matters. See Charles Osenton and Company v. Johnston (1941), 57 T.L.R. 515; Finlay v. Minister of Finance of Canada et al. (1990), 1990 CanLII 12961 (FCA), 71 D.L.R. (4th) 422; and the decision of this court in Attorney General of Canada v. Foundation Company of Canada Limited et al. (S.C.A. No. 02272, as yet unreported). [emphasis added]"

R. v. Tayo Tompouba, 2024 SCC 16 at paragraph 72, contemplates cases where irregularities are so severe that it rendered the trial unfair or created the appearance of unfairness (Khan, at para. 69, per Lebel J., concurring; see also Fanjoy, at pp. 238‑40; Davey, at paras. 50‑51; Kahsai, at paras. 67‑69), such as the occurrence here, and the proceedings generally-speaking.

The Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Babos, 2014 SCC 16, [2014] 1 S.C.R. 309 considered circumstances where where ongoing participation in compromised proceedings would signal a validation of the abuse, whereas the enforcement of a felony of this magnitude would produce a comparable analogue. Per Moldaver J. at paragraphs 76 through 78;

“A stay may be justified for an abuse of process under the residual category when the state’s conduct “contravenes fundamental notions of justice and thus undermines the integrity of the judicial process” (R. v. O’Connor, 1995 CanLII 51 (SCC), [1995] 4 S.C.R. 411, at para. 73). A stay may be justified, in exceptional circumstances, when the conduct “is so egregious that the mere fact of going forward [with the trial] in the light of it [would] be offensive” (Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Tobiass, 1997 CanLII 322 (SCC), [1997] 3 S.C.R. 391, at para. 91). [...] “There are two public interests at play: “the affront to fair play and decency” and “the effective prosecution of criminal cases”. Where the affront is “disproportionate”, the administration of justice is “best served by staying the proceedings” (R. v. Conway, 1989 CanLII 66 (SCC), [1989] 1 S.C.R. 1659, at p. 1667).” [...] “In other words, when the conduct is so profoundly and demonstrably inconsistent with the public perception of what a fair justice system requires, proceeding with a trial means condoning unforgivable conduct.”

Likewise, the Supreme Court of Canada in Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Tobiass, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 391 reflects the guidance shown in Babos at paragraphs 91 and 110;

“The first criterion is critically important. It reflects the fact that a stay of proceedings is a prospective remedy. A stay of proceedings does not redress a wrong that has already been done. It aims to prevent the perpetuation of a wrong that, if left alone, will continue to trouble the parties and the community as a whole in the future. See O’Connor, at para. 82. For this reason, the first criterion must be satisfied even in cases involving conduct that falls into the residual category. See O’Connor, at para. 75. The mere fact that the state has treated an individual shabbily in the past is not enough to warrant a stay of proceedings. For a stay of proceedings to be appropriate in a case falling into the residual category, it must appear that the state misconduct is likely to continue in the future or that the carrying forward of the prosecution will offend society’s sense of justice. Ordinarily, the latter condition will not be met unless the former is as well ‑‑ society will not take umbrage at the carrying forward of a prosecution unless it is likely that some form of misconduct will continue. There may be exceptional cases in which the past misconduct is so egregious that the mere fact of going forward in the light of it will be offensive.” [...] "An ongoing affront to judicial independence may be such that any further proceedings in the case would lack the appearance that justice would be done. In such a case the societal interest would not be served by a decision on the merits that is tainted by an appearance of injustice. The interest in preserving judicial independence will trump any interest in continuing the proceedings. Even in the absence of an ongoing appearance of injustice, the very severity of the interference with judicial independence could weigh so heavily against any societal interest in continuing the proceedings that the balancing process would not be engaged."

The case law in Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, [2019] 4 S.C.R. 653 at paragraph 135 underscores the onerous moral responsibility on the judge to apply the facts and law correctly;

"Many administrative decision makers are entrusted with an extraordinary degree of power over the lives of ordinary people, including the most vulnerable among us. The corollary to that power is a heightened responsibility on the part of administrative decision makers to ensure that their reasons demonstrate that they have considered the consequences of a decision and that those consequences are justified in light of the facts and law."

Finally, a decision must be guided by an internally coherent and rational chain of analysis with respect to the totality of factual and legal constraints that are applicable to the matter. Per Magee (Re) (Ont CA, 2020) at paragraph 19;

“A reasonable decision is one that, having regard to the reasoning process and the outcome of the decision, properly reflects an internally coherent and rational chain of analysis: Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, 441 D.L.R. (4th) 1, at paras. 102-104. In addition, a reasonable decision must be justified in relation to the constellation of law and facts that are relevant to the decision. For instance, the governing statutory scheme and the evidentiary matrix can constrain how and what an administrative decision-maker can lawfully decide. Further, “[w]here the impact of the decision on an individual’s rights and interests is severe, the reasons provided to that individual must reflect the stakes”: Vavilov, at para. 133. The principle of responsive justification means that especially in such high-stakes cases, the decision maker must meaningfully explain why its decision best reflects the legislature’s intention.”

Given the factual basis, the ECJDA being satisfied, and the above case law constraints, there is no conceivable reason why a judge would choose not to stay a $300,000 execution order that was based on the eight 30-minute hearings held in S-220956, which should have attracted a tariff of approximately $4,000. As it turned out, the partiality of the judge, as shown in the transcript is palpable.

I Was Not Permitted to Quote the MacKinnon Affidavits at the Hearing.

I Was Not Permitted to Quote Case Law at the Hearing.

There was No Mention of the Factual Matrix or Case Law in the Decision.

The Decision Also Positioned the Victim as Perpetrator.

Treatment of the scandal in the enforcement court was not only manifestly wrong in refusing to acknowledge the evidentiary record (much of which was sourced from the CAGE and the BC courts no less) and the applicable legal test concerning special costs in Bradshaw Construction Ltd. v. Bank of Nova Scotia (1991), Supra; it was morally reprehensible in allowing a murderous edict to proceed. None of the Affidavit evidence that was submitted to the judge made its way into the decision, which was read immediately following oral submissions, thus indicating that it was written prior to the actual hearing. Under section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, any orders made absent consideration of the facts and applicable law are invalid. Per Charkaoui v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), [2007] 1 S.C.R. 350, 2007 SCC 9 at paragraph 48;

“To comply with s. 7 of the Charter, the magistrate must make a decision based on the facts and the law. In the extradition context, the principles of fundamental justice have been held to require, “at a minimum, a meaningful judicial assessment of the case on the basis of the evidence and the law. A judge considers the respective rights of the litigants or parties and makes findings of fact on the basis of evidence and applies the law to those findings. Both facts and law must be considered for a true adjudication."

The same invalidity guardrail applies to matters where a judge is shown to be biased. The case law in R. v. S. (R.D.), [1997] 3 SCR 484 at paragraphs 106 defines bias as follows;

“A similar statement of these principles is found in R. v. Bertram, [1989] O.J. No. 2123 (H.C.), in which Watt J. noted at pp. 51-52: In common usage bias describes a leaning, inclination, bent or predisposition towards one side or another or a particular result. In its application to legal proceedings, it represents a predisposition to decide an issue or cause in a certain way which does not leave the judicial mind perfectly open to conviction. Bias is a condition or state of mind which sways judgment and renders a judicial officer unable to exercise his or her functions impartially in a particular case. See also R. v. Stark, [1994] O.J. No. 406 (Gen. Div.), at para. 64; Gushman, supra, at para. 29.”

The jurisprudence maintains that partiality is shown when a predisposition informs an actual decision. In the same matter at paragraph 107;

“Doherty J.A. in R. v. Parks (1993), 1993 CanLII 3383 (ON CA), 15 O.R. (3d) 324 (C.A.), leave to appeal denied, [1994] 1 S.C.R. x, held that partiality and bias are in fact not the same thing. In addressing the question of potential partiality or bias of jurors, he noted at p. 336 that: Partiality has both an attitudinal and behavioural component. It refers to one who has certain preconceived biases, and who will allow those biases to affect his or her verdict despite the trial safeguards designed to prevent reliance on those biases. In demonstrating partiality, it is therefore not enough to show that a particular juror has certain beliefs, opinions or even biases. It must be demonstrated that those beliefs, opinions or biases prevent the juror (or, I would add, any other decision-maker) from setting aside any preconceptions and coming to a decision on the basis of the evidence: Parks, supra, at pp. 336-37."

The test for finding a reasonable apprehension of bias is found at paragraph 111 in the same matter;

“The manner in which the test for bias should be applied was set out with great clarity by de Grandpré J. in his dissenting reasons in Committee for Justice and Liberty v. National Energy Board, 1976 CanLII 2 (SCC), [1978] 1 S.C.R. 369, at p. 394: The apprehension of bias must be a reasonable one, held by reasonable and right-minded persons, applying themselves to the question and obtaining thereon the required information. . . . [The] test is “what would an informed person, viewing the matter realistically and practically -- and having thought the matter through -- conclude. . . .”

The jurisprudence outlined in R. v. Curragh Inc., [1997] 1 S.C.R. 537 is clear insofar as court orders informed by bias are void and unenforceable. At paragraphs 92 and 6, respectively;

“Anderson J. correctly recognized that both the common law and the Charter have as their goal the protection of two separate policies. These are (1) to ensure that accused persons are given a fair trial, and (2) to preserve the reputation of the administration of justice. A trial which violates either principle may be an abuse of process or violative of the Charter.” [...] “The significance of a reasonable apprehension of bias was considered by this Court in Newfoundland Telephone Co. v. Newfoundland (Board of Commissioners of Public Utilities), 1992 CanLII 84 (SCC), [1992] 1 S.C.R. 623, at p. 645: As I have stated, it is impossible to have a fair hearing or to have procedural fairness if a reasonable apprehension of bias has been established. If there has been a denial of a right to a fair hearing it cannot be cured by the tribunal’s subsequent decision. A decision of a tribunal which denied the parties a fair hearing cannot be simply voidable and rendered valid as a result of the subsequent decision of the tribunal. Procedural fairness is an essential aspect of any hearing before a tribunal. The damage created by apprehension of bias cannot be remedied. The hearing, and any subsequent order resulting from it, is void. [Emphasis added.]”

In a comprehensive scandal like this one, where every judge had aligned themselves in an unnatural concurrence, a Citizen has little recourse other than the defense of necessity contemplated by Wilson J. in Perka v. The Queen, [1984] 2 S.C.R. 232 at page 273;

“This, however, is distinguishable from the situation in which punishment cannot on any grounds be justified, such as, the situation where a person has acted in order to save his own life. As Kant indicates, although the law must refrain from asserting that conduct which otherwise constitutes an offence is rightful if done for the sake of self-preservation, there is no punishment which could conceivably be appropriate to the accused's act. As such, the actor falling within the Chief Justice's category of "normative involuntariness" is excused, not because there is no instrumental ground on which to justify his punishment, but because no purpose inherent to criminal liability and punishment — i.e., the setting right of a wrongful act — can be accomplished for an act which no rational person would avoid.”

Specifically, a defense of necessity as outlined in the same matter may apply as an excuse and as a justification. In Perka at pages 270 & 279;

"As Dickson J. points out, although the necessity defence has engendered a significant amount of judicial and scholarly debate, it remains a somewhat elusive concept. It is, however, clear that justification and excuse are conceptually quite distinct and that any elucidation of a principled basis for the defence of necessity must be grounded in one or the other. Turning first to the category of excuse, the concept of “normative involuntariness” stressed in the reasons of Dickson J. may, on one reading, be said to fit squarely within the framework of an individualized plea which Professor Fletcher indicates characterizes all claims of excusability. The notional involuntariness of the action is assessed in the context of the accused’s particular situation. The court must ask not only whether the offensive act accompanied by the requisite culpable mental state (i.e. intention, recklessness, etc.) has been established by the prosecution, but whether or not the accused acted so as to attract society’s moral outrage. [...] Where the defence of necessity is invoked as a justification the issue is simply whether the accused was right in pursuing the course of behaviour giving rise to the charge."

What reasonable person would comply with the theft of every dollar they had worked for as a law-abiding citizen, through a weaponized bench?

ONE Exceptional Circumstance is Articulated in the Post-Decision Discussion. #KangarooCourt

Recourse to Regulators

The Matter Ricocheted Past Appellate Venues, the CJC, and the LSBC. More detail [Here].

Commensurate with matters concerning miscarriage of justice and the denial of police response concerning the above, the glaring scandal involving retainer fees was met with a sclerotic apathy. Courts and regulators cannot construe their statutory schemes and/or review processes in a manner that ignores glaring issues, or reasonably expect to pass the buck without conducting the appropriate due-diligence. Likewise, neither the CJC nor the LSBC had agreed to file a motion to overturn the protection order over the BC files, which operates independently of the unconstitutional sealing orders, and which likewise violates settled constitutional law. The citation below in A Lawyer v. The Law Society of British Columbia, 2021 BCSC 914, by way of irony, is from the same judge that had adjudicated the BC files denoted in the Affidavits (Andrew Majawa). There is no greater indicator of bias than the double-standard. Influential networks and private interests shape the conduct of legitimate authorities on a case-by-case basis in today's post-democratic environment.

A Lawyer v. The Law Society of British Columbia, 2021 BCSC 914 at paragraph 63;

“A key principle derived from these cases is that the investigatory powers of a regulator should not be interpreted too narrowly as doing so may “preclud[e] it from employing the best means by which to ‘uncover the truth’ and ‘protect the public’” (Wise v. LSUC, 2010 ONSC 1937 at para. 17 [Wise], citing Gore at para. 29). Thus, in my view, the powers granted to the Law Society by s. 36(b) of the LPA, and as operationalized by R. 4-55 of the Law Society Rules, should be read broadly to permit the investigation of a member’s entire practice, as that may in certain circumstances be the best means to “uncover the truth” and “protect the public” and to determine whether disciplinary action should be taken. Given the context within which lawyers and their trust accounts operate, the broad investigatory power authorizing the Law Society to conduct an “investigation of the books, records and accounts of the lawyer” provided for in s. 36(b) of the LPA and in R. 4-55 should not be distorted to mean something narrower without explicit statutory language suggesting the same: Wise at para. 17.”

Canada (Attorney General) v. Power, 2024 SCC 26 at paragraph 26;

"The Charter must be given a generous and expansive interpretation; not a narrow, technical or legalistic one (Hunter v. Southam Inc., [1984] 2 S.C.R. 145, at p. 156). Charter provisions must be “interpreted in a broad and purposive manner and placed in their proper linguistic, philosophic, and historical contexts” (Reference re Senate Reform, 2014 SCC 32, [2014] 1 S.C.R. 704, at para. 25)."

Smith v. Jones, [1999] 1 S.C.R. 455 at paragraph 55;

“A second exception to solicitor‑client privilege was set out in Descôteaux v. Mierzwinski, supra. Lamer J. for the Court, held that communications that are criminal in themselves (in this case, a fraudulent legal aid application) or that are intended to obtain legal advice to facilitate criminal activities are not privileged. At p. 893 this appears: There are certain exceptions to the principle of the confidentiality of solicitor‑client communications, however. Thus communications that are in themselves criminal or that are made with a view to obtaining legal advice to facilitate the commission of a crime will not be privileged, inter alia.”

Exodus 14:5-7 Reference

Shortly following

CAGE Settlement